“People who write things that mean something, usually they’re a little too personal for somebody else. That’s a risk that has to be taken.”

— Lindsey Buckingham to Rolling Stone, 1984

Side I:

1. Second Hand News

When you and I met, you wore a crimson tank, and I stared at your arms. A stranger to me, you drove to my newly-rented house and helped me lug my old life inside. We were both of us new to the mountain town where we were to spend the next two years. You brought another member of our grad school cohort, and the three of us drank beer, hoisted boxes in the August-Virginia haze, and tried to force my queen-sized box spring up the 1920s-narrow stairwell. (The boxspring ended up on the street, a chunk of plaster on the hardwood floor.)

We were all of us reluctant to give up before the truck was empty; no longer the lone oddballs, we wanted to prove ourselves to these other writers we might call friends.

Before you left that night, I pulled out my guitar. You played “Such Great Heights,” and I laid a clumsy harmony over top. You met my eyes and insisted: I’d hear the shrillest highs and lowest lows. Your voice was crackly, charming.

You had an out-of-state girlfriend, but I wouldn’t find that out for months, until the weekend she showed up holding your hand at our Wednesday-night dive bar. By then I had forced my attention away from you. Our refuge of writers in the rural south was too precious for such a wager.

*

Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks met in the mid sixties. One Wednesday night during Nicks’s senior year of high school, she ventured out to a Christian “Young Life” meeting, where she spotted Buckingham playing guitar and singing “California Dreaming.” She couldn’t resist; she piped in with a harmony line. She thought Lindsey was darling.

Lindsey never forgot Stevie’s voice. Years later, when Stevie was working towards her bachelor’s at San Jose State, Lindsey called her up and invited her to join his new acid rock band, Fritz. By the chilly San Francisco summer, Stevie held no college degree, but her band was opening for Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Chicago, and CCR. She was in rock and roll.

They didn’t write their own songs yet, either Stevie or Lindsey, but their harmonies synced sweet and tight. They grew together those years, in that way you must when your job requires you to slip into you coworker’s chords.

But that was all. The other members of the band, all male, had agreed: hands off the singer. Buckingham’s entanglement with Nicks for those three and a half years was one of ear and mind.

*

“since feeling is first / who pays any attention / to the syntax of things / will never wholly kiss you,” you recited to me in a university parking lot. You did not mean it; we were practicing recitations for a class. “lady I swear by all flowers…. we are for each other.” You swung on “lady,” a monkey bar lodged unexpectedly in my veins.

When I began my own recitation—“You do not have to be good…”—my voice shook.

For a gestation period, we wrote and read and recited and edited, you and I. I read your poems and you read my stories, and you suffered my poems and I suffered your stories, and we complained about the workload, though it was the best work of our lives. You read about my father’s addictions, and I read about your mother’s depression. We both read Dillard and Carver and Wright and Doty and far too many undergraduate writers who wrote angry stories about sexist men, maudlin ones about dead childhood dogs.

We found each other’s eyes during class, at readings, across the fields on campus and at parties outside the cabin you rented. We sat in the tall grass around bonfires you built and drank late into new mornings, when everyone else had turned to water or sleep.

We crossed no romantic lines.

*

I know you’re hoping to find

Someone who’s going to give you peace of mind.

When times go bad,

When times go rough,

Won’t you lay me down in tall grass and let me do my stuff?

2. Dreams

In 1971, Fritz broke up, and Lindsey and Stevie got together. “Pretty soon we started spending all our time together,” Nicks told Rolling Stone in 1977. The duo moved to Los Angeles, armed with sparkling demos and a belief that they’d bag a record deal.

Buckingham worked on his music. Nicks worked as a waitress and a cleaning lady to make ends meet. “You have to understand,” Stevie told SPIN in 1997, “I didn’t want to be a waitress, but I believed that Lindsey shouldn’t have to work, that he should just lay on the floor and practice his guitar and become more brilliant every day. And as I watched him become more brilliant every day, I felt very gratified. I was totally devoted to making it happen for him.”

It did happen, for him and her both: they got a deal, with Keith Olson as their producer, to cut an album called Buckingham Nicks.

*

It was nearly summer again the night you ran your fingers through my hair.

What did we discuss—cut peonies in a mason jar on a wrought-iron table, bottles of wine empty on front porch floorboards—? Women, I think: those you were eying, the one whose heart I’d just bruised. You had left the out-of-town girlfriend by then, but a summer back in your hometown shimmered like a fresh new try.

When we said goodnight, your lips moved toward a whispered kiss, but my arms were already around your neck. Your fingers found my hair. Alcohol and familiarity, all. You’d spent the evening dreaming, out loud, of other women.

Into the night—warm and humid like the day we’d met—you flew.

*

Buckingham Nicks flopped. Polydor Records dropped the duo, and their manager released them from their contract. Back to work went Stevie, and Lindsey back to staying home, all day playing guitar. “We were broke, and we were starving, and we needed money,” Lindsey told Creem in 1985.

But he didn’t help bring the money in. Not yet, anyway.

*

The morning I woke with you in my bed, the days had grown long. Even so, the sun had hardly risen when you pulled on your jeans and patted the back pocket to ensure the small black notebook you carried everywhere was still there. I grabbed my cotton robe and walked you to the door, same spot where your lips had wanted mine a week before. For the first time in many months, we did not hug goodbye.

*

Thunder only happens when it’s raining.

Players only love you when they’re playing.

Say women they will come and they will go.

When the rain washes you clean, you’ll know.

3. Never Going Back Again

In an interview with BBC in 1984, Lindsey admitted that he and Stevie “always competed…ever since we started going together back in 1971….even though we were excellent lovers, we were competitors as well.” Even so, when Mick Fleetwood invited him to join Fleetwood Mac as the band’s new guitarist, Buckingham was clear: to bring on Lindsey was to bring on Lindsey and Stevie both. Their record may have tanked, but Buckingham and Nicks were still a package deal.

Playing in a new band—a genuinely famous one—didn’t cure the couple’s musical tension, nor did it seal the fault-lines in their relationship. Shortly after they’d joined, Stevie walked in on Christine McVie and Lindsey harmonizing on a song they’d just written: “World Turning.”

Stevie and Lindsey had lived and worked together for years, but not once had the two of them written a song. This was infidelity beyond body.

*

After you left that morning in May, I vowed to cut down on my drinking. It was to blame, I decided, and if I wasn’t careful it’d blow up our friendship. I told no one of our tangle, not even my roommate who, surely, through the thin 1920s walls, had heard.

That summer I went dry and tried to work out what had transpired in the last year of my life. I’d loved a woman. I’d loved a man—you—though I wasn’t ready to say so.

You were home in Pennsylvania, and I was working on a second masters in Vermont. I wrote to you about Calvino, Smith, Espada. You’d been working too many hours to read, living at home to try to save enough money to get through the next year of grad school. You wrote to me of your new dog, named after a writer we both loved. You knew, your slanted script proclaimed, that he’d love me.

*

Been down one time.

Been down two times.

I’m never going back again.

4. Don’t Stop

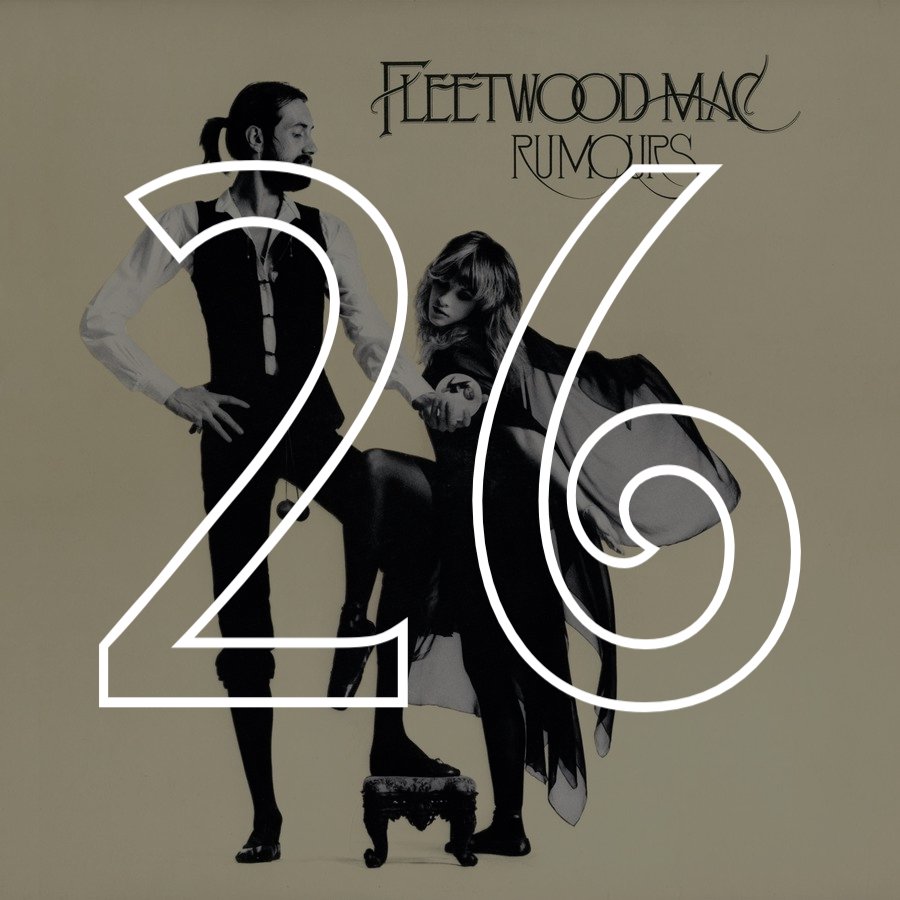

Everything the other did was wrong. Lindsey was an asshole. Stevie was a drag. They were both doing too much coke. “Try working with your secretary in a raucous office…then come home with her at night,” Nicks told Rolling Stone in 1977. “See how long you can stand her. I could be no comfort to Lindsey when he needed comfort.” In the same article, Lindsey admitted, “I’m surprised we lasted as long as we did.” Stevie was the one to end things, but they both knew the break was coming.

During the year that Fleetwood Mac wrote and recorded Rumours, there were long stretches when Nicks and Buckingham refused to talk. They sang in harmony, stared into one another on stage, but didn’t speak.

Instead, they wrote about their relationship, in songs the other would be required to perform. They punished each other in licks and lyrics.

But when Lindsey heard “Dreams” for the first time, he made eye contact with Stevie and smiled. “As musicians, we still respected each other,” Stevie explained to The Daily Mail, “—and we got some brilliant songs out of it.”

*

August. You and I both back in Virginia. You were the first to reach out. You were helping a new professor move into his on-campus home and would I like to join? We’d had such fun the last time, a year before, almost to the day.

I declined, but soon we were in your car together, both our dogs in the backseat, driving to a waterfall. Your dog threw up ten minutes outside of town, and I did the cleaning. For a moment, I felt I was proving something—giving you a glimpse of who I’d be as a mother, a wife. I shook it off. That wasn’t what I wanted.

Back on the road, I told you: I’d stopped drinking. My shoulders shrugged tight as I said it. You’d see it as a critique, I thought. So many of our shared hours we’d swum silly and happy in booze.

“You know,” you said. “I’m never really happy when I’m drinking. I’m something, but not happy.”

I nodded and we drove in silence to the falls, a sight that could kill us if we got too close, but, from where we stopped, just whispered mist. We crouched before thousands of cubic-feet-per-second of pounding water, held tight to our dogs, and grinned.

*

All I want is to see you smile

If it takes just a little while.

I know you don’t believe that it’s true:

I never meant any harm to you.

5. Go Your Own Way

“Tell me why everything turned around,” Buckingham signs on the fifth song on Rumors. “Packing up, shaking up’s all you want to do.”

Stevie was livid, but she hurled her harmonies over her ex’s brutal lyrics all the same. A cap put on their love, they boiled for one other in a different way.

One night during a show, Lindsey approached Stevie and kicked her, not enough to hurt her, but enough to spark an eruption. “He went off, and we all ran at breakneck speed back to the dressing room to see who could kill him first,” Stevie told Rolling Stone. The band’s bodyguards had to pull Stevie off of him.

*

On my 29th birthday, you and I met in a parking lot just off the Blue Ridge Parkway. I got out of my car, and you kissed me, as if you did that every day. I took your hand.

We drove for hours. We kissed on small trails, at the edge of overlooks, in your car, breathless for what we’d been pretending not to want.

At my birthday dinner that night, you sat separate, careful not to hold my eyes or hand. We acted like nothing had changed.

*

Loving you isn’t the right thing to do.

How can I ever change things that I feel?

If I could, baby I’d give you my world.

How can I when you won’t take it from me?

You can go your own way…

6. Songbird

Lindsey had wanted his freedom, but he still resented Stevie for breaking things off. He’d been tossed around enough.

Even so, the two stayed in the Mac, long after each had written bitter words about the other, over a decade after Rumours was complete. Success is the best revenge, and they were competitive still. But when first Nicks and then Buckingham decided to cut solo records, they cheered one another on. Six years after their relationship tanked, Nicks told The Record, “I love Lindsey. I love him very, very much….For me, when you love somebody, you want them to be the best.”

*

I was in the last year of my twenties, the second year of a graduate arts program, when you got so under my skin that I agreed to love without strings. There were new girls in our program, and, well, you wanted to meet as many different types of people as possible.

You never were one for strict syntax.

At post-reading receptions, I’d sip a club soda and watch you flirt with other women, knowing I’d give myself to you later. I’d drive you home when you’d had too much to drink. I’d wake hours before you and lie in your bed, listening to birdsong.

Some weeks you’d bring me flowers you picked from the wilds around your cabin, take me on mushroom hunts in cool morning mist. Some weeks you’d hardly meet my gaze until, a party emptying, you’d find me: your dependable second choice.

You insisted we keep it all a secret. It’d get too messy if everyone found out. Really, you knew my power in that small group of writers. If those first year women had known, they would have let you be.

I learned to be present. Your arms, twice as thick as mine, belonged to me only for the instant I was in them.

*

And I wish you all the love in the world,

But most of all, I wish it from myself.

And the songbirds keep singing

Like they know the score.

And I love you, I love you, I love you

Like never before.

Side II:

1. The Chain

In interviews, Stevie and Lindsey don’t talk much about their relationship prior to joining Fleetwood Mac. In their songs on their first album with the band, though, they say plenty:

Buckingham: “First you love me, then you fade away. I can’t go on believing this way.”

Nicks: “Well, I’ve been afraid of changing ‘cause I’ve built my life around you. But time makes you bolder, even children get older, and I’m getting older, too.”

Buckingham: “I’ve been alone all the years. So many ways to count the tears. I never change, I never will.”

In truth, joining Fleetwood Mac both severed and chained Stevie and Lindsey. Their romantic relationship, already off-again, on-again, could no longer endure; their professional one could not be broken.

*

You began to moan other women’s names in your sleep. Other women I knew, whose writing I read, who read mine.

That was it: I wanted you to myself, and I wanted to say so out loud. When I made my ultimatum, you said you were sorry.

We saw each other nearly every day—on campus, at parties, at our weeknight dive bars, where I sipped club soda with lime. But we did not speak. It was then that you first made your way into my stories. It was then that I slipped into your lines.

*

Listen to the wind blow, down comes the night.

Running in the shadows, damn your love, damn your lies.

Break the silence, damn the dark, damn the light.

And if you don’t love me now,

You will never love me again.

I can still hear you saying you would never break the chain.

2. You Make Loving Fun

What is the measure of what’s worth it for art?

It’s no secret that Rumours hit like it did because of its haunting mix of bone-break lyrics and melodies so upbeat they claw into your mind, playing themselves and their barbed lyrics on repeat.

Near rending, plastered-smile insistence to hold on, the energy of atomic fissure. It makes gut-wrench love sound fun.

*

You asked if we could talk in December. We met at our Wednesday night dive bar and sat across from one another at a booth. Some game was on TV. Yes, you said, looking at the television screen, then at me. Yes, you’d do it. You’d be in a relationship. You had missed me.

It was December and it was cold and it was nearing the anniversary of my mother’s death. I stood and joined your side of the booth. I curved myself under your arm.

*

Don’t, don’t break the spell.

It would be different, and you know it will.

You, you make loving fun,

And I don’t have to tell you, but you’re the only one.

3. I Don’t Want to Know

Nicks wrote “I Don’t Want to Know” during the Buckingham Nicks years, before Fleetwood Mac was even a possible pitstop in their unmapped future. Though the tune’s treatment of infidelity fits in nicely with the rest of the record, it wasn’t supposed to be on the album.

“Silver Springs,” which has since been included on remastered versions of Rumours, was to be in its place, but Nicks’s new song was too long. The other members of the band made the decision to cut “Springs” without Stevie, recorded her old tune with Buckingham on both harmony and lead, and then begged her to sing over his lead part.

She wanted another songwriting credit on the record. She fumed, but she went along with the plan.

*

By Valentine’s Day, you were texting her every day. We still hadn’t gone public with our relationship. She did not know.

On that day of coupled love, you posted two pictures on social media: one of your dog in an empty guitar case (mine, but she would not know that) and one of your dog’s face close to your lap.

You made sure I wasn’t in the frames.

She Liked both pictures. You stared at your phone. I worked on my novel, furious.

When I gave my thesis reading the next week, you left the seat I’d saved you empty, sat on the other side of the room. Dozens of pictures were snapped that night, but in all the ones that show me, you’re absent from the frame.

*

Finally, baby:

The truth has come down now.

Take a listen to your spirit—

It’s crying out loud,

Trying to believe.

Oh you say you love me, but you don’t know.

You got me rocking and a-reeling…

4. Oh Daddy

I was always the one to end it. This time, it happened outside a diner. You’d been texting her, again, during breakfast.

But I didn’t mention that. Instead I tried to make summer plans, post-grad plans, what-are-we-doing-with-the-rest-of-our-lives plans. “If you’re so unsure about whether you want to be with me in three months,” I said, “I don’t see why we’re together now.”

Presence, your lesson, always. An exam, with you, I always failed.

*

Years later, after I moved to North Carolina and bought my first house, I pulled Rumours out of one of the same boxes I’d brought to Virginia. This time, the boxes were carted in by movers I’d hired. This time, there were no gouges in the stairwell.

The record turned up too loud, I danced in my empty house the way the Mac’s beat insists. I unpacked plates and forks and mason jars and set them gently on wooden shelves. I pushed the furniture that had once been my mother’s from one room to another. Unconsciously, I began to sing along with Stevie and Lindsey, then got catapulted back to you.

*

If there’s been a fool around,

It’s got to be me.

Yes, it’s got to be me.

5. Gold Dust Woman

Who sheds an addiction easy?

Though Nicks was by all accounts the most successful of Fleetwood Mac’s members after the band began to go downhill, she was also the one cocaine hooked the hardest. Before Rumours’ ten-year anniversary, she’d developed a hole in her nose, lost her voice, and crumpled under a new addiction to Klonopin, prescribed to help her shake coke.

She’d dated other men, and, for three months, even married one, but she remained devoted to Lindsey. As late as 2009, she told MTV, “Who Lindsey and I are to each other will never change.”

*

For a year, I quit booze and got my highs and lows from you, but it’d be years more before we left each other’s veins.

When I left our mountain town in Virginia, you and I spent another August day hauling furniture and boxes. You emptied the house you’d filled. We cried when we parted, but that was not that.

Once, you nearly came to D.C. for me.

Once, I nearly moved to Pittsburgh for you.

Once, we met each other halfway, in a town in West Virginia, and before I drove off, you told me—to my face—that you loved me.

*

Well did she make you cry,

Make you break down,

Shatter your illusions of love?

And is it over now? Do you know how?

Pick up the pieces and go home.

Postscript:

Silver Springs

Now, in 2019, Stevie Nicks is preparing for a world tour with Fleetwood Mac, and Buckingham’s not. The ostensible reason: timing. The reality? When asked last year about the band’s decision to tour without Buckingham, Stevie told Rolling Stone, “Our relationship has always been volatile.”

They met. They created. They entangled. They split. They channeled it all into art.

Lindsey Buckingham has been married to a different woman for nearly twenty years. He has three children who aren’t Stevie’s, and a net worth of around eighty million dollars.

Stevie Nicks’s net worth is estimated at seventy-five million. She’s happily unmarried and free. In 2012 she told CBS This Morning, “I have lots of kids. It’s much more fun to be the crazy auntie than it is to be the mom, anyway. I couldn’t do what I’m doing if I had kids.”

Hers is a household name.

*

You aren’t my you anymore.

We’ve seen each other since our last split. Conferences. Weddings. We’re chained to the same field, same handful of beloveds.

Last summer, you sent me a contributor copy of a journal where a poem of yours appeared. I looked for my prints on your words: maybe, find each other, change, Coronas. In a letter, you asked when you’d be seeing my work in a journal. Excellent lovers, once; excellent competitors, still.

Will we do this always? Hunt evidence of what we were and are in the marks the other makes on a page?

I promise you this: I won’t make you sing my lines out loud, or force you to look me in the eye and harmonize. But I think Nicks was right. You never escape the hold of the ones who loved you. You never shake the sound of the ones you managed to love.

And can you tell me, was it worth it?

Baby, I don’t want to know.

—Ellen Louise Ray