#454: Alice Cooper, "Love It To Death" (1971)

It would be nice to walk upon the water, to talk again to angels on my side.

—Alice Cooper, “Second Coming”

My grandfather once told me about trick or treating when he was a child. There was one house that gave out king-sized candy bars, and the way he tells it, he and his friends would spend Halloween night changing from one costume to another so they could keep going back to that same house. The way I imagine it, he has to walk up and down the sets of rolling hills that characterize Cincinnati—butterfly hills, I used to call them, for the feeling they made in my stomach. I can picture my grandfather at twelve, trudging up hill after hill, carrying a plastic pumpkin just like I used to, filling it with king-sized candy bars. First he’s a pirate and then he’s a ghost and then he’s a mummy and then he’s a farmer. At the end of the night he has twelve costumes and twelve candy bars. I wonder why the people at this house never noticed it was the same person returning again and again, but maybe the point is that they did notice, and they didn’t care.

My cousin drowned when he was nineteen. It was Halloween night, or, to be more specific, the early morning hours of the Day of the Dead, and he jumped into the Mississippi down in New Orleans, where the river is so wide it carries ocean-faring ships and is hardly recognizable as the same river that flowed past my house in Minneapolis when I was growing up. Sometimes, in my head, he jumps off a bridge that looks suspiciously like the Golden Gate. Sometimes, he runs along a rickety dock and dives off the end. An old man is fishing, and stares after him in surprise. At this point, I no longer remember which of these scenarios—if either—is correct. I know that he had taken acid. I know that he had given his dog to a friend to take care of. I know that I was in eighth grade and had just come home from school when I found out. I was eating the last of the fall crop of raspberries off the bush in the backyard, and my mother came outside and told me. I had a raspberry in my mouth, and I started crying, and even as I cried, there was a part of me that thought how interesting it was that I could go from one emotion to another so quickly, that a person really could suddenly burst into tears.

I visited the ruins of Troy, in Turkey, when I was in college. The ancient city is more like a town, with crumbling walls overrun by grass and weeds. A large wooden horse stands near the visitor’s center. It has a house on its back with windows, like a tree house, and children clamber up and down the wooden steps and wave from the windows to their parents. I wonder what the Trojans would think of the joking way we refer to their plight. A man approached me as I was standing outside the gift shop, getting ready to leave. I’d become distracted by the litter of stray kittens climbing in and out of cracks in the stone walls. “Excuse me,” he said. “Excuse me! I heard you speaking English.” This is what I hate most about traveling, I have found: the men who will use any excuse they can find to tell women of their beauty, to ask for their number, to ask for their hand in marriage. I prepared to ignore him and walk away. “Excuse me,” he said again. “I am hoping you can help me. You speak English. I have always wondered—what is it, the difference between ‘Oh my God’ and ‘Oh my gosh?’”

Illustration by Annie Mountcastle

Maybe there’s some sort of lesson here, about trusting strangers, about not closing yourself off to an experience before it’s occurred, about how reality doesn’t always match up with what you imagine. When I imagine my grandfather, when I imagine my cousin, I’m nowhere close to what actually happened. And when I think I know what a stranger is going to say, there’s always room to be surprised. Maybe this is what life is always trying to tell me, and I should listen more closely.

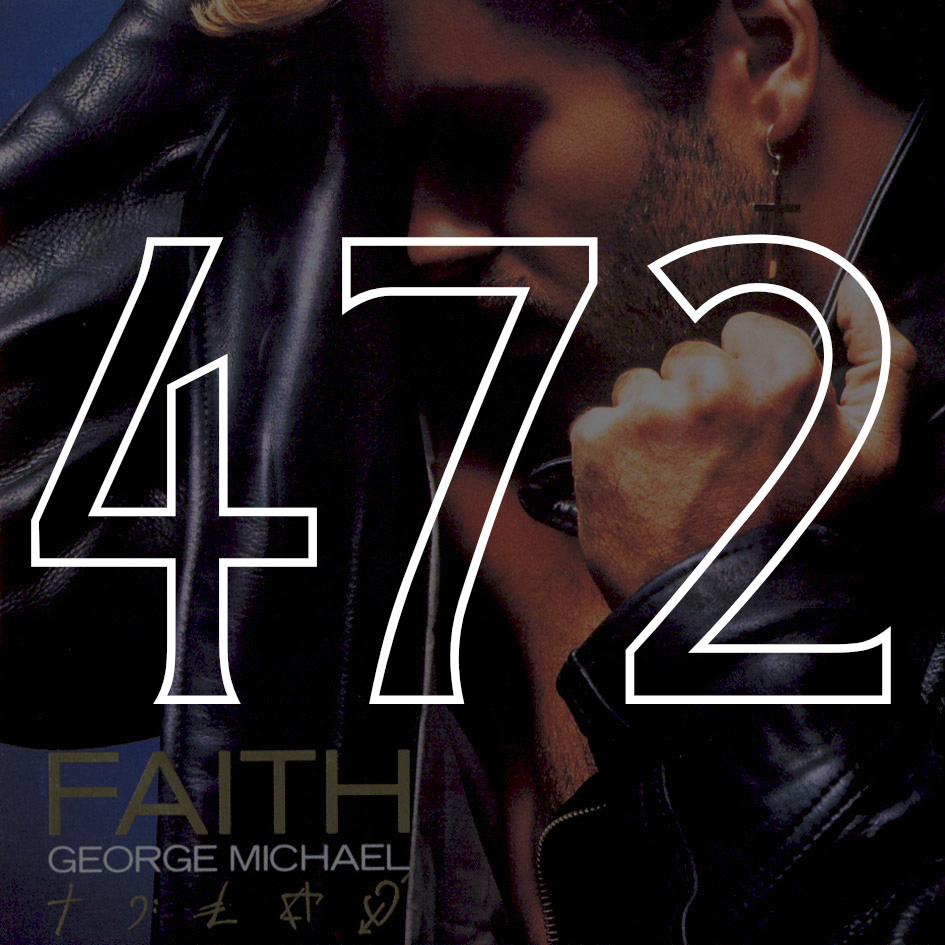

I watched a video of Alice Cooper performing during their Love It to Death tour in 1971. The video quality was poor, the picture grainy, with static bursts every few seconds that broke up the chords. When he sings “Second Coming,” Alice braces himself against the stage wall. His mascara creates tears on his cheeks, and he holds one hand to his head, as though he can hardly bear what is happening. “Have no gods before me, I’m the light,” he cries, his voice barely audible over the guitars, and then he staggers back from the microphone, his hands pressed to the sides of his head. He stumbles off the stage, almost falling, looking as if something inside of him has broken. When he returns, he’s in a straitjacket.

I don’t remember what I told that man in Troy. I probably said something about how saying “Oh my God” can be considered taking the Lord’s name in vain, and so people use “gosh” instead, out of fear of offending someone, be it God or a human being. That, I feel, is a fairly accurate answer to his question. But I wish I hadn’t explained that. I wish that I had told him that there is no difference, that they are both ways of evoking the sacred, of marveling at or bemoaning life and its always-fluctuating circumstances. I wish I had told him that it didn’t matter.

The closest I’ve ever come to walking on water is over frozen creeks and lakes. In places, the water freezes so clear you can see through to the rocks that line bottom. You can see weeds, suspended in ice, looking as if they might break free at any moment and continue to bend and sway with the current. It’s disconcerting, and sometimes, if I stare too long, it makes me dizzy.

I am not a person who searches for the larger meaning in the things that happen to me. I don’t read the myths and apply them to my own life. Because the fact is, the city of Troy would have had a sentry set up at night, and he would have noticed the Achaeans climbing into that wooden horse, and he would have woken someone up. And maybe my grandfather did return over and over to one house in search of king-sized candy bars, and maybe it’s just a story he told us because we were children and would believe anything. The cold, hard facts are that my grandfather will not live much longer, and the city of Troy is in ruins and I no longer can remember what I thought of as I toured it, and I will never be able to appreciate Alice Cooper the way people say I should.

But what I have instead is this: one of the last times I saw my cousin, we were in the Colorado Rockies. We climbed up a small mountain, one of the mountains with a wide path and steps carved into its side, with lines of people making the trek from a visitor’s center just a few hundred feet below the summit, up and back down in the span of an hour. My cousin would be dead just four months later, but of course we didn’t know it then. There’s a picture of him and me and my younger sister at the summit, all giving each other bunny ears, my sister and I on tiptoes to reach the top of my cousin’s head. Shortly after the picture was taken, at my cousin’s suggestion, we ran back down the mountain. We leapt down the shallow steps, let the air rush past us, traveling at top speed from above the tree line to just below it, from thin air at altitude to a place where there was oxygen aplenty, past tourists who waited until the last minute to leap out of the way, our mouths open and the wind carrying away our laughter, and when we reached the visitor’s center, for a few minutes, none of us could breathe.

Oh my God, we said. Oh my gosh.

—Emma Riehle Bohmann