Maybe it was something like this:

A lie started it all.

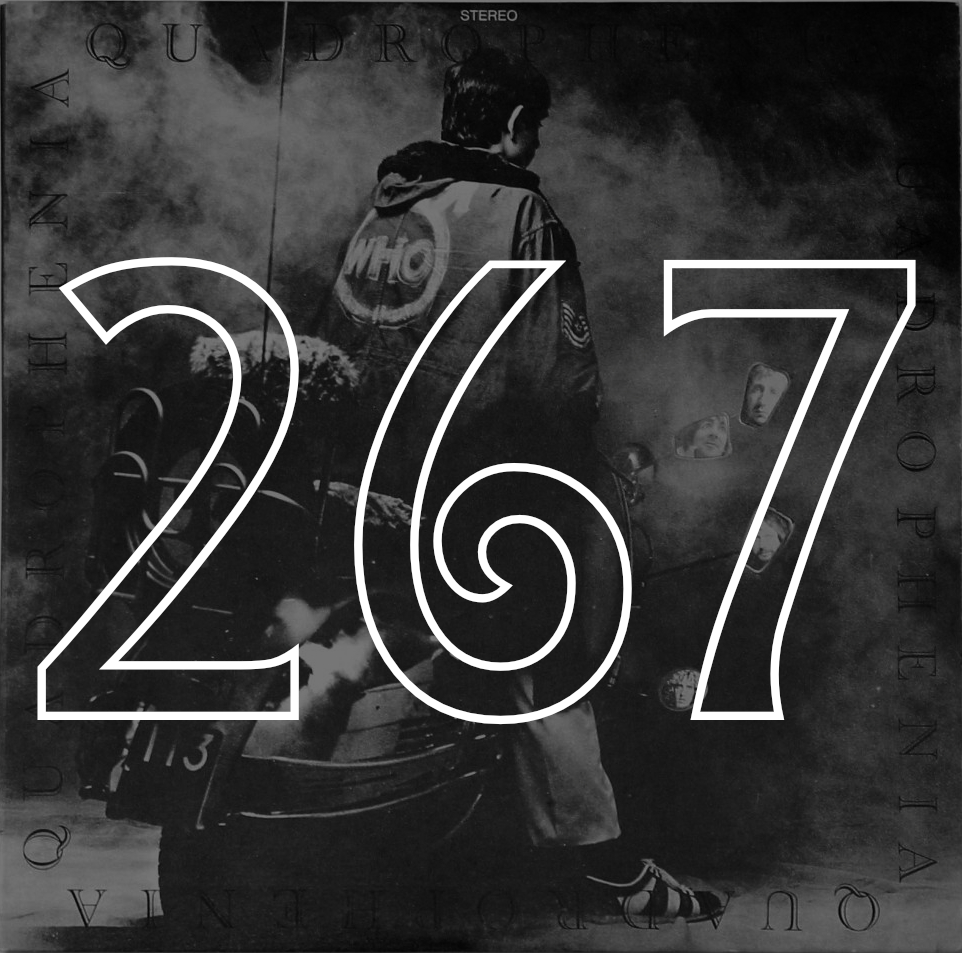

It just slipped out, as he, Scott, sat there on the couch with his new friend—his only friend, at least in town—playing air drums to the new one.

Because how could he not?

Because Keith Fucking Moon.

The parts that weren’t weird, anyway. The parts that sounded like a band playing, instead of—well, whatever was happening.

Wow, man, Mike said. You’re good.

Thanks.

You play?

Yeah.

I mean, yeah, you play, Mike said. Obvious from watching you. Like, you still play? You playing?

Totally. I mean, not with people. Not yet. I just got here. Haven’t found anyone. But yeah. I do.

And this was the lie: before moving from Iowa, Scott’s drums had been gathering dust in the basement. They probably still were, unless his parents moved them. Mom always talked about wanting space for a sewing machine.

And he hadn’t found anyone yet because he hadn’t looked. Not with any focus. He wanted to play music, sure, but he wanted to keep doing his artwork.

And he wanted to take it all in.

He could walk to the ocean. The ocean! Water was water, as far as he was concerned—at least before he’d seen it, so different from the Mississippi, huge and powerful and unspeakable.

He tried to articulate the ocean to his parents and felt stupid as soon as the words fell from his mouth into the phone receiver. Because of course it was big, and of course it was beautiful. But there was more, and he couldn’t wrap words around the way wave after wave crashed into the bridge stanchions, tireless and unrelenting. How the air felt in his lungs.

The hills—he’d heard. And he was excited for them, even as they kicked his ass and he whooped for breath, that amazing ocean air he couldn’t appreciate because he insisted on keeping a normal pace—he was a fast walker—and even after he’d been there a while he still found himself having a hard time, but he loved it. Muscataine was built on bluffs, but nothing like even the routine hills.

And Muscataine was part of the Quad Cities, had its neighborhoods, but it didn’t sustain itself the way San Francisco did, reaching out seemingly endlessly, always with something new, some restaurant or record store, some shift in tone, in feel. So many beautiful people in one place, more than he’d ever seen. So many homeless. So many students. So many businessmen. So many cars. Trains. He still didn’t understand the trains.

And as much as he wanted to think tapping out paradiddles on his knees counted as playing, it didn’t. He knew it didn’t.

But it had come out. The lie was out there.

*

Mike knew a guy who got the British music newspapers, the ones that always arrived a month late and cost way more than Rolling Stone or Creem. They pored over these, weaving their news into the conversational fabric passed as currency.

The news of the Who’s return to the U.S. was in the British mags, of course—but no specifics. And it wasn’t until a few days after the sale that Mike heard about the lines stretching from the box office in Daly City. This, too, became part of the fabric, how the queue had been a huge party, a real cool time. They’d missed it, heard about it, tried to own it through inflation. When he told his new friends—Mike’s friends—about the line, how they hadn’t heard, he tried to possess it by exaggerating. By making up details, turning what had probably been a few joints and a pizza into something like Woodstock. He hadn’t been—he was too little, it was too far—but he understood that the experience had grown since it happened, and would continue to, as long as the bands were popular. And they would be forever, thanks to Janis and Jimi, who had themselves been inflated.

None of it was a lie, exactly. But it was out there.

*

A knock on his door.

It was Mike—who else could it be?—but frantic. Excited.

How much money you got?

Huh? I don’t know. Why?

You know that guy Jesse talked about?

Scott heard the blood pounding in his temples. You mean the guy who waits out for tickets?

You know where this is going, right?

Are you serious?

He’s got two, and he said he’d hold them for me for an hour.

When is it again?

Friday.

Work.

But he hadn’t called in sick yet.

He would if he couldn’t find someone to cover his shift.

Scott disappeared into his room, returning with a tin can full of change. He dumped it out on the coffee table.

Help me count it out, he said. We have to get into that show.

*

The Cow Palace was part of the fabric—one of the places Bill Graham booked. Had it been him that put on the first Beatles show in the States, in the Cow Palace? Scott didn’t think so, but he wouldn’t’ve been surprised if it was—Bill Graham did everything.

Including hiring a ton of security guards.

They’d counted the money, bought the tickets, decided to go as early as possible so they could get right up front. He imagined trying to articulate the feeling of Daltrey’s mic whizzing overhead, how that air was somehow being shared by him and his favorite band. Trying to articulate the feeling of Townshend’s sweat hitting him, how he knew he should be grossed out but wouldn’t be.

How Moon’s drums were going to hit him right in the chest, over and over again.

Right in the heart.

And all this would turn out to be great, of course, and then some.

Instead, he tried to imagine some way to describe the utter boredom of waiting in line.

Scott felt stupid about the falsehoods he and Mike had woven about the ticket line, the one where Jesse’s sketchy friend had presumably waited to get tickets. About how he’d turned what he thought had been a few joints and a pizza into Woodstock.

He didn’t know if the guards were actual cops or not. He wasn’t sure it mattered. Bill Graham didn’t take any shit, not since (he’d heard) the thing happened with the MC5, when biker bouncers broke Graham’s nose. He’d heard the shows were strict, but he didn’t know he’d be, like, surveilled for thirteen hours.

Thirteen.

Hours.

This will all be worth it, Mike kept saying.

He wished he’d brought a deck of cards, or a book. The kid behind him had Vonnegut, a girl a little ways behind was reading Fear of Flying. Everyone was too scared to blaze up, too scared to crack flasks under the gaze of the positively terrifying security.

*

And then they were in, running.

(A few years later Scott got word of Cincinnati and thought it could have been any of us. It could have been me.)

Pretty much front and center, against the barricade.

The security between them and the stage weren’t the black-clad guards who’d been watching the line outside. They were just normal guys. A little older, maybe, but cool. They talked with Scott and Mike and everyone else up front during the wait.

Yeah, one said, Moon’s crazy.

You met him?

I met them all.

Whoa.

Like, he hasn’t stopped since he got here. I used to hear all the stories about him and thought they couldn’t be true because the dude would just be dead. But they’re true. I saw with my own two eyes.

I hope it’s not all new stuff, Mike said, after Skynyrd.

From behind, someone yelled holy shit, it’s them!

They all walked onstage and Scott couldn’t believe it, how close they were. How real they were, after so many years of British music magazines one month late and photos and stories passed like currency.

They ripped into “Can’t Explain” and Scott grabbed Mike’s shoulder and jumped up and down, up and down, singing along through “Summertime Blues” and “My Generation.”

It cannot get any better than this, he thought as Daltrey swung the mic and just as he’d hoped, the air, Daltrey’s mic air, pushed his hair back, the drums thumped heartbeat time against his chest. He thought that he’d never be able to explain it, no words.

He even lost himself in the new stuff. It would have been better if they hadn’t been playing along to a tape or whatever was happening, but still—the air, the thump, Entwistle holding it down, Townsend’s leaps. Thinking back, he was transfixed, utterly hypnotized.

It went so fast.

And then Mike broke the spell during “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

Something’s wrong, he said, pointing to Moon.

Scott was glad for this. He thought he’d noticed, too. But come on. Keith Moon. Keith fucking Moon wouldn’t drop time and lose beats. He was too good.

Then he slumped against the kit.

The crowd cheered, unabated, lights still down. Maybe people in the back thought things were normal at first. But word must’ve spread, right? Like it always did.

The security guy up front shrugged. The amount he’s been drinking, not surprised. And people gave him gifts beforehand.

What kind of gifts?

The guard laughed. Fucked if I know. Probably some kind of fish paralyzer.

They all came back on, waving, and went into “Magic Bus.”

And again, he hit the kit.

Daltrey and Townsend and Entwistle played it off like it wasn’t a big deal, like food poisoning or something. But Scott thought about the bouncer, the gifts—who knows what Moon had taken. Were fish paralyzers even a thing?

After a drumless “See Me, Feel Me,” Graham got up there. Scott knew it was him from the magazines.

CAN ANYONE HERE PLAY DRUMS?

Mike elbowed him.

That’s you, man!

CAN ANYONE HERE PLAY DRUMS?

Scott thought oh, shit. I haven’t played for a year! More!

Townsend: Someone good!

Mike gestured to the guard. Hey, man! This guy! This guy right here! You know us! This guy can play! He can play!

The guard looked at Scott.

He thought of his hometown, the city.

The lie that started everything.

Trying to find words, failing.

The exaggerations.

If I don’t do this, he thought, what will I say?

What can I say?

He nodded. The whole thing was built on bluffs.

The guard extended a burly hand.

No way, Scott thought. This cannot be happening.

He grabbed the guard’s arm and hopped the barricade, Mike too. He was walked up the side stairs, lights rendering everything silhouette and haloes.

Everything except for Bill Graham, who stood between him and the stage.

What’s your name, kid?

Uh, Scott. Scott Halpin.

If you’re pulling my leg, I’m—

I’m not pulling your leg, Mr. Graham. I’m a drummer. They’re my favorite band. I know all the parts.

Silence.

I can do this.

All right, Graham said, leading him by the elbow onto the stage, the stage at the Who concert, his favorite band.

Leading him to Townsend.

Here’s your drummer.

Scott felt himself shaking like a leaf as Townsend stared into his eyes.

Want some brandy?

Scott nodded.

What’s your name?

Scott repeated his name.

All right, Scott. You’re going to be great. Right? I’m going to lead you. Watch me. I’ll cue you.

Someone produced the brandy, which he slugged. It helped a little.

He sat behind the kit and took Moon’s sticks, fully intending to his each drum a few times. He tried to imagine how much work it would be to set up so many toms before every show, break them all down. There were roadies for that, or course, guys paid specifically to perform such tasks. A regular guy like himself wouldn’t have room in his station wagon for so many toms, in bags or more likely hardshell road cases, but what did a station wagon matter to fucking Keith Moon? He didn’t care.

Yeah, he fully intended to try them all, but before he realized what was happening he started “Smokestack Lightning,” which he knew.

What he didn’t know, not until later, was that he didn’t have to exaggerate, didn’t even have to try and articulate what was happening, the wave after wave of noise he was creating behind Keith Moon’s kit, crashing against the back of the Cow Palace. There weren’t words for it, anyway, this chance to sit with his favorite band, the best in the world, behind that kit for three songs. There was no need to articulate what was instantly and irrevocably woven into the fabric.

—Michael T. Fournier