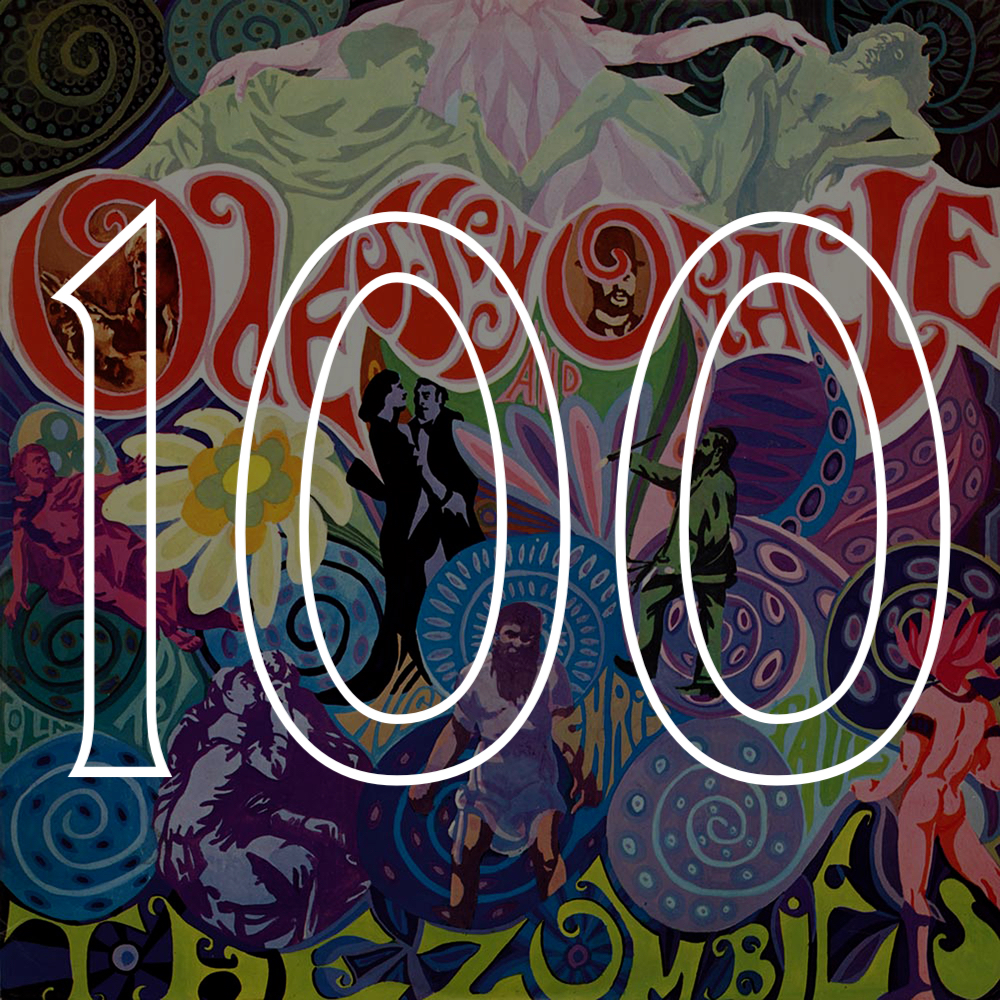

#100: The Zombies, "Odessey and Oracle" (1968)

The summer of 2000 I was working for a small company just outside of Dayton. I’d be into work by 8 and home by 4:30. It wasn’t a great summer job, but the pay was good enough to keep me in records and help pay bills when I was back at school in the fall. I took apart old metal shelves that were no longer in use and swept out an empty warehouse space that the company had recently decided they no longer needed. While working in the empty warehouse, I somehow listened to music. Maybe I had a boombox? Something with a tape player on which I could play mix tapes? Maybe I just had a Discman? I don’t remember. Probably the boombox with tapes I made from my slowly growing collection of vinyl LPs. One of my best finds that summer was a used copy of the 1997 UK repressing of the Zombies’ Odessey and Oracle. I copied it to a tape to listen to in my car. I hadn’t known about the album for long, having previously and recently heard only “Beechwood Park” thanks to a mix given to me by a friend. I listened to the album at least a hundred times that summer. I was struck by the way most of the songs sounded like the past. But not “the past” as a particular moment in music history, but like someone remembering the past—those languorous tempos and reverb-soaked vocals begging listeners to remember whatever it is they desperately need to remember.

*

On the Fourth of July, we rode in the back of a friend’s pickup truck to see fireworks. I moped because I couldn’t stop thinking of an earlier Fourth of July when I was falling in love with a girl named Jess, holding her hand and stealing kisses during fireworks. That previous summer, the one with the earlier Fourth of July—the summer of ‘98—ended almost as soon as it started, that girl and I holding on to each other for dear life as my departure for college grew nearer. To help slow the passage of time, we went for long, slow walks through neighborhoods and parks. One night we got lost in a nature preserve and had to wade through a waist-high creek to get out, unable to navigate to a more convenient exit after the sun abandoned us. Another night, we walked through the neighborhood adjacent to my parents’—Beechwood Springs, the development was called— and we stopped at a park there, called Beechwood Springs Park. Bathed in moonlight and dripping with humidity that made our hair wild, we alternated between kissing and talking about a future that, realistically, we probably knew we weren’t going to share together. At the time, I didn’t know that a song called “Beechwood Park” existed, but had I known, I’m sure it would have been a favorite. Soon, though, summer ended and I went away to college. The relationship didn’t last past October, and I carried that loss with me for years, the way foolish young men sometimes do.

*

Most nights that summer of 2000, I’d meet with my friends at Denny’s, where we’d play euchre and smoke cigarettes. One night, while sitting at Denny’s, a man walked in the front door, picked up a fork, and stabbed that fork into another man’s head. I don’t know if they knew each other. Another night, a man OD’d in the bathroom. When police showed up, they found with the man a shopping bag full of bloody clothing. I don’t know why I remember these when there are so many other things I’d rather remember but cannot.

*

One Saturday in June, I came across the Clientele for the first time, found the Fading Summer EP at a record store in Cincinnati. This was a couple of weeks before I picked up and first heard Odessey and Oracle in its entirety. I was struck by the way that the Clientele sounded somehow simultaneously new and old, and always wistful. Even after I started listening to Odessey and Oracle obsessively, I frequently returned to Fading Summer—the Clientele kind of sounded like the Zombies, but filtered through cheap speakers and mixed with either ten percent more humidity or twenty-five percent more autumn chill, depending on the song. Regardless, both bands’ baselines seemed to be deep summer nostalgia. If both albums sounded nostalgic, I remember thinking, then maybe the Clientele were the more nostalgic of the two because of the distance between performance and sound implied by the mid-fi production in which the songs were wrapped.

*

That summer of 1998, Jess wore something, some sort of lotion or spray, with a fake vanilla scent to it. To this day, when I catch a whiff of that very specific, surprisingly rare scent, I remember more about that summer than usual.

*

But back in the summer of 2000, at work, I befriended the other guys in maintenance. They handled the real shit and gave me the special projects that none of them wanted to do. That was fine. They were nice to work with. When I turned twenty-one in August, they wanted to take me out for a ball game and a beer. I couldn’t make it because I was going to see some bands play in Michigan. The day I got back from that birthday trip, I was taking some metal shelves apart and one of the guys caught me singing along to “Strawberry Wine,” by Deana Carter, which had been playing softly over the PA, and which I’d not heard before that summer. That summer, though, when I was working in the main building, I heard that song at least once every other hour.

*

Some nights, when it was too early for friends to be at Denny’s yet, I’d kill time by driving to Miamisburg, across the river and up the hill, out to the house where my family lived for the first five years of my life. I don’t remember why I’d do that. Even then, I had only the vaguest recollections of living in that house. I’d drive to the end of the dead end street on which it sat, look at the house, then look at the large, empty field that ended the street—I’d feel some heavy sense of nostalgia, then I’d turn around in the driveway and head back down the hill and across the river towards Denny’s. One night, I parked my car a few streets away and walked to the middle of the field. I sat down and put on my headphones. I had my Discman with me, and the aforementioned mix with “Beechwood Park.” I put that song on repeat and looked up at the sky, then looked out of the field back at the neighborhood where I used to live. I don’t know what I hoped to see there. I remembered climbing the tree on the edge of the yard, and half falling out of it once. I remembered, one street over, a patch of apple trees that didn’t seem to be on anyone’s property, where my mother would take me to puddle jump when it rained in the summer. I remembered non-descript kids on bikes, the green glow of my dad’s old stereo receiver. I remembered the long, slow summer days spent outside, being read to under a tree by my mother. It was an easy, lovely childhood.

*

Another night in 2000, late, after the Denny’s crowd disbursed a little earlier than usual, but not really early at all, I returned to my parents’ house then walked to Beechwood Springs, parked my car on a side street and walked to the park from two summers before. I don’t remember having music with me, but I remember lying on a picnic table and smoking a cigarette and looking up at the starless sky. I tried to remember the way everything about my previous night at that park felt. I couldn’t—those feelings remaining stowed away just out of reach. But what I could remember was comforting, as if the memories could speak and were saying, “Of course you’ll someday feel those ways again.”

*

In the summer of 2014, I picked up a copy of the Clientele’s stunning first album, Suburban Light, the one compiled mostly from early singles and EPs, including selections from the Fading Summer EP. Printed on the insert was this quote from Joë Bousquet’s “The Return”: “The loveliest of the stars has raised up the night so as to blind me with its infinite presence; my gaze is submerged, like a silver ring tossed into the flood of my heart.” I’d never encountered Bousquet’s work before buying that record.

*

Now, in 2018, I am approaching forty and summers feel hotter. The dry heat burns harder and the humidity feels heavier, a wet hairshirt woven from memory. Some days I think that the heat should be unbearable, but really it’s not, because encoded in that heat is close to four decades of summers. Some nights, I almost feel as if, were I to squint hard enough, I might see the water everywhere in the air around us, and if I squint harder still, I might see fragments of my past at play with all that water.

*

The part of this story about Jess, it has a happy ending. I’m not sure it’s worth mentioning as this essay isn’t really about that, I don’t think. But maybe you should know that she and I are married now. We were apart for twenty-odd years, then somehow we found each other again. I’m not sure why or how it happened. We’re very different people, now, but it works.

*

Since the summer of 2000, I’ve visited places important to my past at least a dozen times each: Denny’s (until it closed), the old house and the field beside it, the park where Jess and I got lost and had to wade through a creek to get out. At times, I felt as if I was stalking my own history, shellacking each layer of new memory with nostalgia, so that now, when I visit the park in Beechwood, I remember the dozen or so other times I’ve visited since, as if the wistful nostalgia I felt on those subsequent visits has written itself into the narrative of that place almost as much as the initial visit in 1998. Almost.

*

I don’t know why reverb and lush production make me think of my past. I don’t know why young men and middle-aged men and old men are so inclined to remember the past through a nostalgic lens. I don’t know why we feel the need to try to reclaim our pasts even when we know they can’t be reclaimed. I don’t know why some days I feel old and tired and other days I feel young and excited. I don’t know much of anything about anything except the way that reverb and vanilla scent make me remember, and that’s not really important, anyway.

—James Brubaker