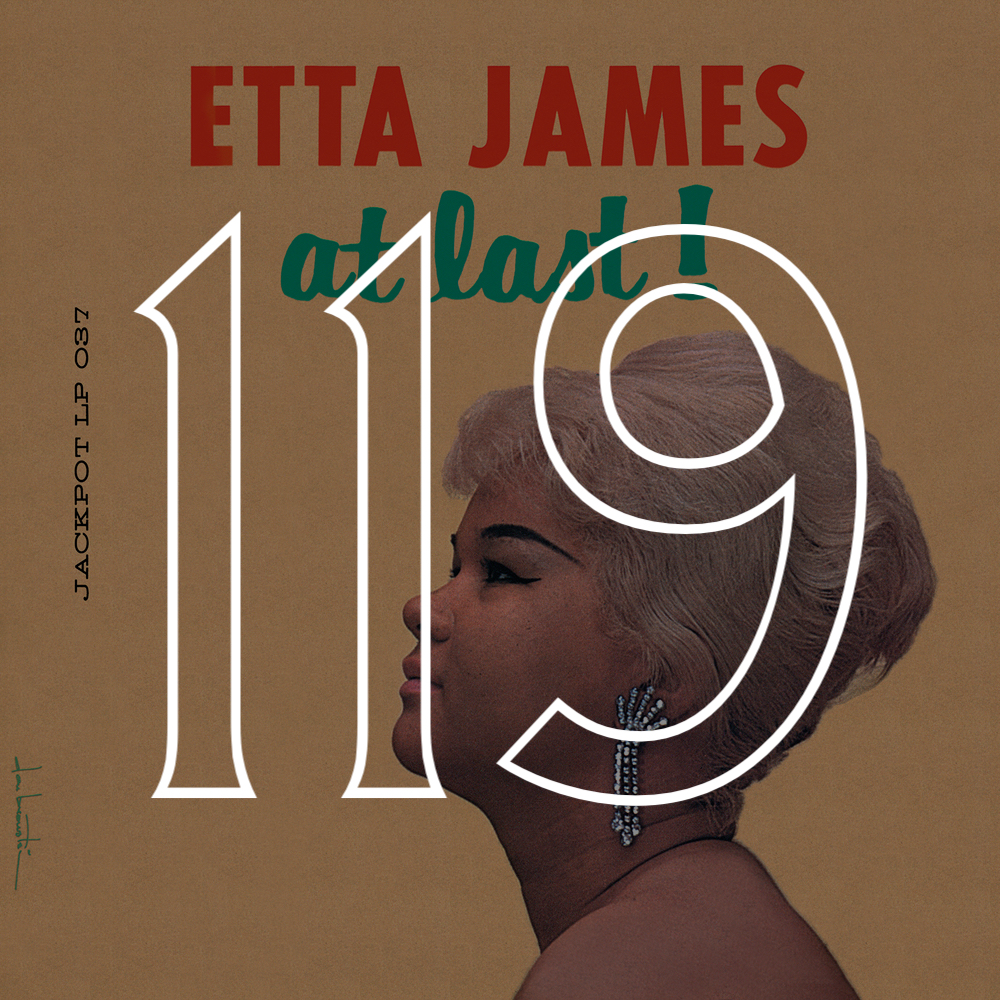

#119: Etta James, "At Last!" (1960)

Abigail’s older sister didn’t understand why their father kept his old records when just about everything was available on CD and BMG would send you 12 CDs for the price of one, delivered right to your house. You couldn’t even listen to records in the car, Sarah said. Their 1989 Chevy Blazer had a tape deck so their father always had to bootleg records onto cassette to play his favorite songs on road trips, but Abigail loved those mixtapes, their father spending hours picking and cueing up just the right songs in just the right order and timing the record and the tape deck perfectly.

While Abigail appreciated the novelty of the BMG mail order forms with the little postage stamp album covers that you tore off and attached to the 12 little squares to choose the CDs you wanted, she loved her father’s record collection, loved it physically, the large cardboard covers, the way some of them folded open, displaying more artwork or lyrics, the paper sleeves nestling each vinyl disk. She loved that her father kept his favorite records in a wooden milk crate on the floor next to one of the speakers, loved the dusty smell of them, loved that he bought most of them before she was born.

She loved the sound, that initial pop and crackle, as the needle was carefully, so carefully, dropped at the first track, a process you got to repeat for the B side, and if you were really lucky and he was playing The Wall or Tommy, you repeated again and again for sides C and D.

Her favorite was Etta James’s At Last!, the strings on “Anything to Say You’re Mine” swelling from out of that initial pop, James’s imploring voice following directly. She loved the earrings that James wore on the cover, the style of her hair and long, thin eyebrows. When she was older, Abigail thought, she would do her eyebrows that way, she would have earrings like those.

Abigail wasn’t allowed to put records on herself, her father afraid she would scratch them, afraid she wouldn’t be careful enough with the needle, which made her love them all the more. So sometimes when the girls were home alone she would put on a record, drop the needle gently, so gently, on to the groove and listen to the familiar pop and hiss, Sarah threatening to tell on her, but the warm sounds worth the risk. And some nights, when she was sure everyone in the house was asleep, she would sneak down to the basement and plug in the headphones with the extra long cord and listen to an album or two, an hour stolen in the night that was all hers.

*

She loved the records, and the records taught her about love. Her friends all thought love was Disney stories, happily ever after, but the records taught her the truth. Sometimes love is work. Sometimes love goes bad. Her father’s country albums taught her that sometimes people cheat, sometimes people leave you. The doo-wop and girl groups taught her that you have to pledge your love, have to make promises that even those bad times won’t end your love. You have to promise that nothing, nothing, nothing can come between you. That’s what love is.

*

When she was little, Abigail loved to sing. Not in front of people, not to perform, but she would just sing. “Twinkle, Twinkle,” “If You’re Happy and You Know It,” or “The Wheels on the Bus,” she would sing these songs to herself while playing. She would sing them at the dinner table, in the car. Her parents would praise her, tell her how well she sang, but it was never about that, never about being good or about grown-ups’ praise or even their enjoyment. The songs just came out of her. She felt happy when she sang, so she sang a lot.

Her parents would often ask her to sing a song when they had friends or family around. They’d have a few beers, listen to music, and then before she went to bed they’d ask her to sing for their guests, so she would sing a few songs and all the grown-ups would clap and she would feel embarrassed because they clapped, not happy like the singing made her feel, but still she did it because the grown-ups liked it and she trusted them.

*

The records taught her about trust and love. She learned that she should hold out for a “Sunday kind of love,” a love that was more than the happily-ever-after, the love-at-first-sight the movies promised, a love that would “last past Saturday night,” though she had no idea what that meant. She figured that she would understand when she was a grown-up. But even if she didn’t know what it meant, she knew it was true because Etta James told her it was true.

*

When her mother went into labor with her younger brother, her parents dropped her and Sarah at her aunt and uncle’s house for the night while they went to the hospital. Uncle Grayson was her favorite, the one who could get her to sing whenever he asked, the one who made her laugh. But he was also the one who could hurt her most deeply, the one who could make her cry easier than any other grown-up could.

That night he had some friends over to play poker in the basement, the men sitting around a card table drinking Coors Light out of silver cans and playing five-card draw for pocket change and dollar bills. Before bed, Aunt Mary dressed Sarah and Abigail in their matching nightgowns and took them down into the basement to say goodnight to Uncle Grayson. He asked her to sing a song, so she did. She sang “Twinkle, Twinkle” and all the men clapped around their beer cans and whistled with cigarettes still hanging out of their lips. Uncle Grayson kissed the girls and they went upstairs to bed in the spare room waiting for news of their baby brother.

*

The records taught her that love was something people made to each other. She wasn’t sure what that meant, but the way Etta growled it out sent goosebumps down her arms. Whatever it meant, it was serious to make love to someone.

She couldn’t wait to be a grown-up.

*

Love was completion, the records taught her, so in that way she guessed Disney got it right. When you found love, when you found that Sunday kind of love, you were whole, and it was forever, you were never alone, and life was perfect. True love, she learned, was what was promised in songs.

She loved her family. She loved her parents and her baby brother. She loved her aunts and uncles and cousins. She even loved Sarah, even though Sarah was a know-it-all and a tattle-tale and often a bully, but still she loved Sarah because sometimes in the night she would have bad dreams and Sarah would make room in her twin bed and let Abigail cuddle up to her until the bad dreams went away and she could sleep again, and Sarah never called her a baby for having bad dreams or for still wetting the bed, the thing that Abigail was most embarrassed about. In those moments Sarah was kind to her and protected her, and she loved Sarah more than anyone in the world. But that didn’t last very long because Sarah would soon be mean to her again or tell on her and she would forget she loved Sarah.

She loved her family and she loved her father’s records, but she knew that true love, the real love that records promised, was something completely different, something she wouldn’t feel until she was a grown-up.

*

That night Uncle Grayson woke her up in the spare room where she and Sarah were sharing a double bed. He was drunk, and she could smell the beer and cigarettes on him. “Abby,” he said. “Come on Abby. Come sing for us again.”

He pulled her out of bed and dragged her down to the basement where the men were still playing poker. He stood her in the middle of the room and said, “Come on, Abby. Sing us a song.”

The men implored her to sing. She rubbed her sleepy eyes. She didn’t feel like singing, but all the men were looking at her and waiting for her, so she started to sing “Row, Row, Row Your Boat.”

Some of the men sang along with her, their rough voices slurred and staggering, others clapped. But then one of them pointed out that her nightgown was soaked in urine, pointed out that she had wet the bed, and they all laughed at her, even Uncle Grayson, until she ran back upstairs to the spare room.

She cried until she woke Sarah up, but she wouldn’t tell Sarah what was wrong, what they’d done to her. She was too embarrassed.

She would never tell her parents what had happened. She wouldn’t tell anyone what had happened, not for many years when she was an adult and had found people who genuinely loved her and who she trusted completely. It wasn’t the trauma that kept the story secret, but the fact that she continued to wet the bed even much later, all the way until she was twelve years old. Even with lovers and close friends, she wanted to hide that long into her twenties because perhaps they would judge her, perhaps they would laugh at her the same way.

*

She would never tell her parents what Uncle Grayson had done to her, but she refused to sing after that. For a while they would ask, their friends would ask, her aunts and uncles would ask, but she would just bow her head and say nothing until they stopped asking. She learned to hate being the center of attention, she learned to hate people staring at her, waiting for her to do something, expecting something of her. Eventually they stopped asking.

She even stopped singing when she was alone, when she was playing in her room by herself. That part of her life was clouded over now, no longer brought her joy. She loved to hear other people sing, just as long as she didn’t have to be the one to do it.

*

That was in part why she loved her father’s records so much, she would realize much later. She loved the voices of strong women like Etta James, like Billie Holiday or Patsy Cline or Janis Joplin, women who wouldn’t let the world silence their voices no matter the adversity they faced. She would realize and understand all of this much later when she was a grown-up and had been able to look back on her childhood with a critical eye. But at the time all she knew were the sounds of the needle dropping gently, carefully, that pop and sparkle, and that the first notes swelling out of the vinyl grooves was as close to true love, true happiness, as she’d ever felt.

—Joshua Cross