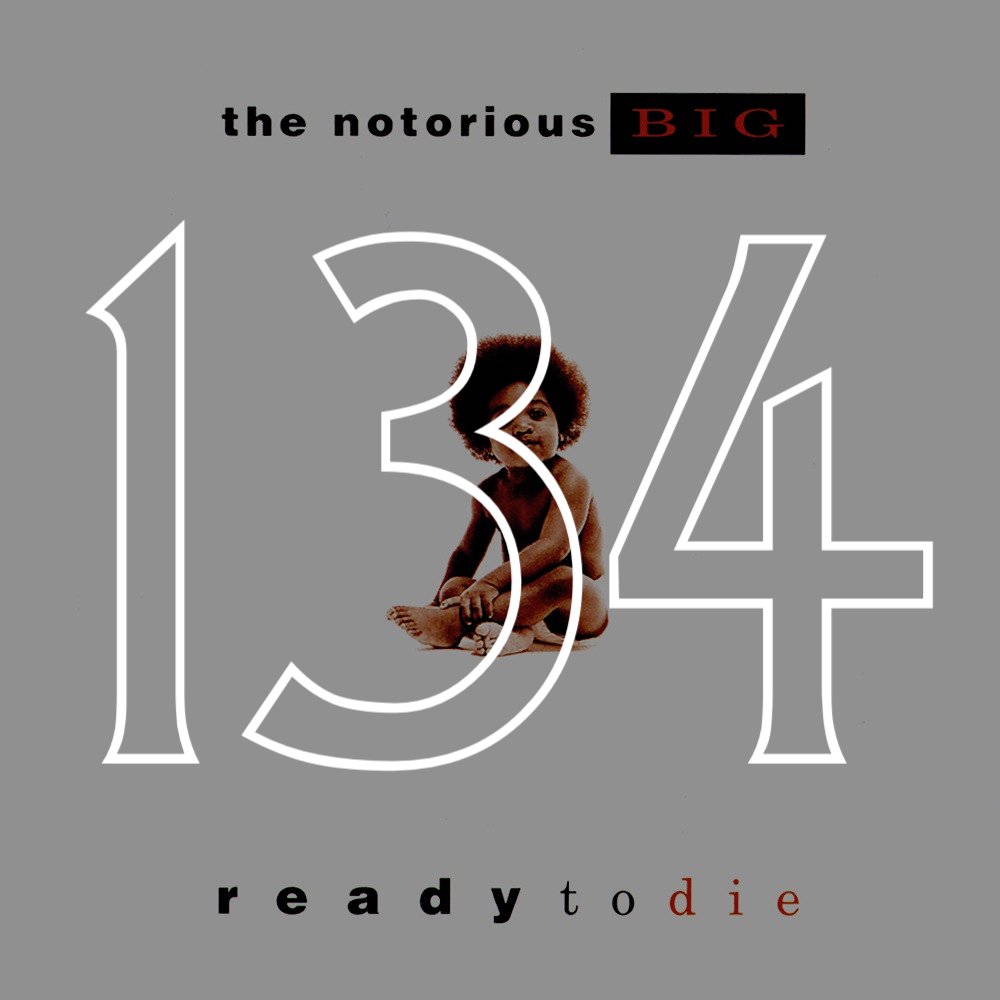

#134: The Notorious B.I.G., "Ready to Die" (1994)

My family on both sides came to the United States in the late 19th century from Scotland and Ireland and settled in Cleveland, upstate New York, and New York City. I do not know if the phrase “American Dream” was in the parlance of their peers, if that storybook quality I now project onto their immigration story was at all a reality. If there was a fantastic opportunity sought here, what it ended up looking like was a locksmith business on Staten Island; a food brokerage firm in Buffalo; the New York State Police; and services in the United States Army, Navy, and Air Force with all of these accomplishments arrived at in the 1940s and 1950s. My brother, my cousins, and I are—as of 2018—the ultimate result of this pursuit, this dream.

I’m 25. I have a college degree. I work for the U.S. government. I have a car. I rent a house with two friends from high school. I’m unmarried. My mom, in thirty years of working in telephone companies, ended up making more money than me and my partner will make combined. In other words, there is a way in which the dream plateaus and a non-American group is normalized. The dream looks more like how it looks on Atlanta, where at every level on the ever-expanding and mutating spectrum of success, what you are left with at the beginning and end of a generation is a cheap “hustle,” some labor you produce while telling yourself you’re doing something else, going somewhere important.

A similar sense of dissatisfaction—not even disillusionment—is apparent in the suffering heart of Ready to Die, Biggie Smalls’s first record, and the only one released in his lifetime.

My introduction to Biggie was through VH1 programming, some specials on the history of hip hop, some lists of celebrity feuds, and some specifically about the relationship between Biggie and Tupac, the tragic and legendary rivalry that now acts as the gravitational center of ‘90s rap. I knew nothing of Biggie’s music outside of its association with violence and profanity. It wasn’t until I was 17 that I first had an impression of his skill and character, in a car full of young white teenagers rapping along to “Juicy;” I was the only one in the car who didn’t know every single word.

And “Juicy” is certainly one of the best—if not the best (and by a mile)—songs that the United States has produced about the “American Dream.” It’s the dream as witnessed in Biggie’s life as his impoverished childhood and hardworking mother somehow nurture in him the peerless capacity to rap, through which he becomes a superstar, The King. Echoing the introduction to the album, Biggie narrates his growing up in the context of his hip hop heroes:

It was all a dream

I used to read Word Up! Magazine

Hanging pictures on my wall

Every Saturday Rap Attack, Mr. Magic, Marley Marl

The song about Biggie’s life is by extension a song about the success of hip hop itself. He reminds listeners of its underdog status as a form of art (You never thought that hip hop would take it this far) and that he—Biggie—is its greatest product and purveyor.

But there is a tension between what “Juicy” is and what Ready to Die is. The opening song is “Things Done Changed,” a story about his world getting worse, not better. Biggie opines the increasingly violent state of things and the senseless corruption of his neighborhood normalcy:

Back in the day our parents used to take care of us

Look at ‘em now, they even fucking scared of us

Calling the city for help because they can’t maintain

Damn, shit done changed

While Biggie himself will see opportunities opened to him, more and more doors are closing to family and friends as economic conditions worsen. He watches as younger and younger kids get involved in the nightmarish world of drug distribution. With what is perhaps the most understated lyric of the album, he concludes “Things Done Changed” by telling the listener that his mom has breast cancer.

Biggie is obsessed with death in broader terms as well, telling the listener on “Ready to Die,” “Everyday Struggle,” and “Suicidal Thoughts” that he wants to kill himself, somewhat against the tone set by the underlying beat. The sound of Ready to Die is the sound of Mafioso rap, hip hop with nostalgia for crime, music that relishes what crime can afford the criminal. This can in part be credited to the orchestral soul sound of the beats, best exemplified on “Warning,” which samples Isaac Hayes’s “Walk on By”: electric wobble, symphonic purr, a mix of the psychedelic funk of Sly & The Family Stone and the lushly-arranged backing orchestrations for ‘50s jazz vocalists, something sexy and luxurious. A similar sound is used on “Things Done Changed,” which prominently features harp, and “Ready to Die,” with its distinctive wah-wah and crying strings. “Gimme the Loot” and “Everyday Struggle” have beats that sound genuinely fun, if not childlike. This is the music underscoring an album called Ready to Die.

At every turn, the celebration of newfound wealth and acclaim is measured against an alternate reality where Christopher Wallace is not the exception to the rule. Biggie’s survivor’s guilt is carried above him like the sky over Atlas. His “Suicidal Thoughts” stem almost entirely from guilt and shame:

All my life I been considered as the worst

Lying to my mother, even stealing out her purse

Crime after crime, from drugs to extortion

I know my mother wish she got a fucking abortion

For each “Juicy” there’s a “Things Done Changed;” for every “Big Poppa” there’s a “Me and My Bitch,” a song detailing the death of Biggie’s love by a bullet that was intended for him. This theme of dichotomy has been played out most recently in Kendrick Lamar’s 2017 album DAMN., where opposing tracks (“Lust” and “Love”, “Pride” and “Humble”) play out the opposing beliefs and priorities of the modern U.S. resident. For every winner, there is a loser; for every moral, there is an economic or social incentive to act in its opposite. What was once an “American Dream” of opportunity could now be best described as a zero-sum game: the process by which one achieves success or acclaim might necessitate an alienation from that which gave you humanity.

The iconic image of Biggie wearing a crown speaks to his often uncontested spot as greatest rapper to have ever done the thing, with more than a few of his songs now canonized as summer barbecue standards and synonymous with celebratory atmosphere. This reality has to square with the artist’s own obsessive fear of violence, fear of being a father, fear of economic insecurity, a lack of trustworthy friends, and his self-acknowledged capitulation to the hopelessness provoked by it all.

—Jeremy Johnston