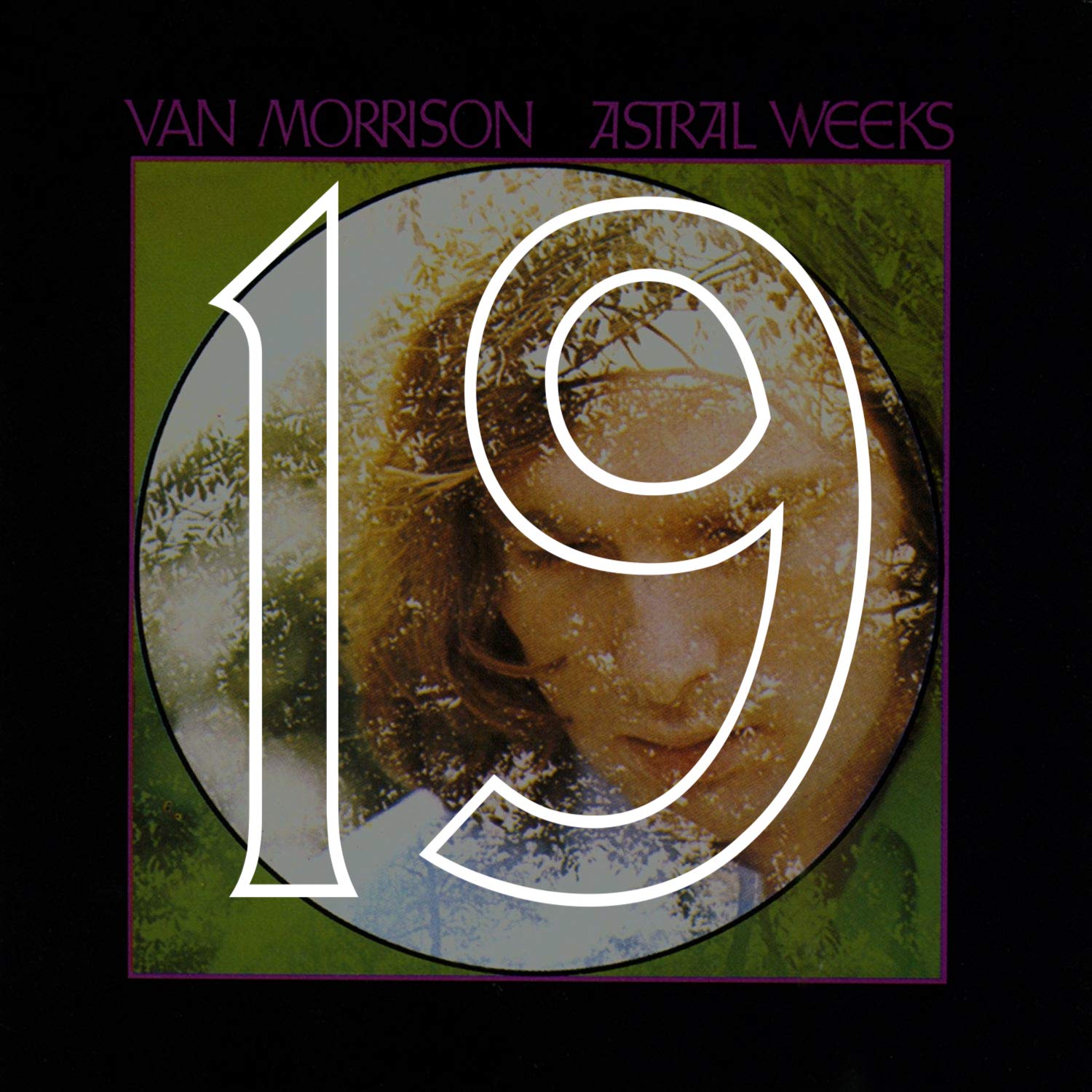

#19: Van Morrison, "Astral Weeks" (1968)

for Papaw

There was once a time when the Appalachian Mountains we drove by every summer looked like apricots from the backseat where I sat. Sometimes, my papaw would point them out. Often, we just kept driving through the West Virginian viaducts. In those days, he wore plaid button-down shirts tucked into his denim Wranglers. He kept a ballpoint and a handkerchief in the chest pocket, and I loved poking the fabric with my tiny index finger. I was the only person in the entire world allowed to drink Coke in his car, which wasn’t a special car, just a normal Buick he bought on a lease, and that small allowance was, at the time, everything to me. The way the pop fizzled as it sloshed against the aluminum tab sharp enough to cut my tongue drowned out the acoustic music oozing out of the car radio. I never knew what song it was until I was older. As a boy, I knew it as the song that said: “Would you kiss my eyes?” It always felt like 106.5 played it every year as we drove alongside eroded rocks ready to cascade down onto our car. I used to dream about those mountains, though. I always wondered if Papaw dreamt about them, too. Down a road made of dirt, that was somehow jagged like kitchen knives, the log house he was born in was gone. A man in a pair of black work overalls told him it’d been knocked down years ago, but he was wary of that, because he could still see the stains and indents in the earth where the foundation once sank into. Before I was born, he knew he’d have to one day try and explain to me how the bodies we’d grown to love and live in would crumble. His sister held a map of Central West Virginia up to the sun coming through the windshield and his finger, blackened from years of grease and truck driving, pointed at a speck about a nail’s length from where our car was. I remember the sound of his finger tracing the lines on the map. The way the friction of all of that could even make a sound amazed me. He pointed towards a mountainous ripple on the paper. The sound of that friction often returning when his hand would scrape the wall at night while he slept, until his fingers curled into a fist that he’d use to punch people in his sleep. When he woke he couldn’t remember any of that. When I was in that car, I thought being a man meant knowing where home is. He didn’t care about the flowers blooming near the plot of land he grew up on. To be born again. Instead, he fixated on how the road hadn’t been paved once in the seventy years since he’d left. He thought it would be different. Better. Some years after, I held his hand while lung cancer feasted on his body in the same way his hand would reach into the backseat and hold me against the polyester while the car twisted around the sharp turn of the Devil’s Elbow outside Morgantown. Bedridden, high on morphine, he whispered something about mountains in his sleep, and I waited for him to say it again, pretending I didn’t catch it the first time, but the summer breeze coming through his window ruffled whatever gray hair he had left, and the sun grabbed tight and stripped him away. To be born again.

—Matt Mitchell