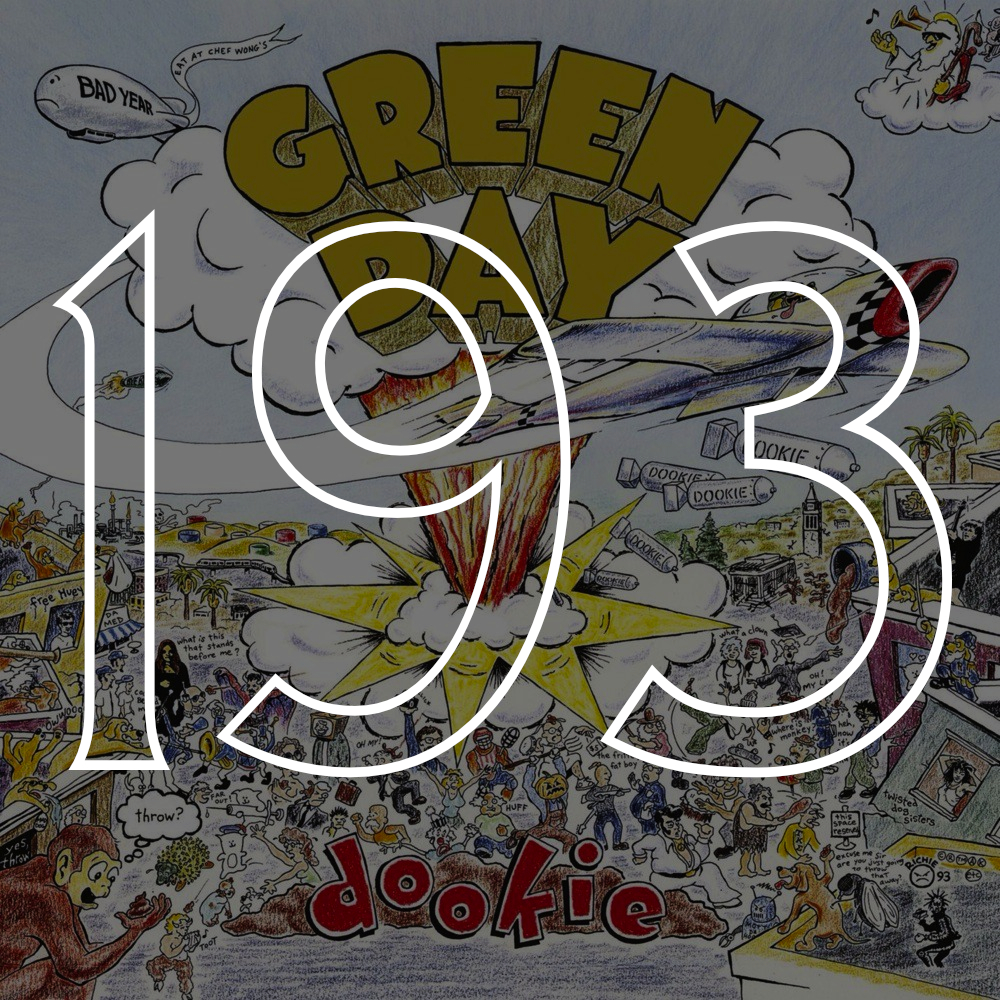

#193: Green Day, "Dookie" (1994)

I don't think I've felt like I wasn't faking something, at least to some degree, since I moved to Washington, D.C. over a year ago. I left at the height of a neurotic episode that partially upended my life and was then thrown into the city’s perpetual rat race of the worst sort. Things that would generally be considered casual hangs have turned turn into unsought networking occasions, and, thanks to the bounty of things to do in the district, every event to which I reply “interested” on Facebook is a direct reflection upon my tastes, priorities, and ultimately my value as a person. It’s so easy to want to be everything at once when everything seems to be at your doorstep. It’s infinitely harder to be any of it. In a city demanding forward momentum and clear vision of yourself and your future, I perpetually feel like a pretender, a thief.

There was no worse thing to be at my middle school than a poser. I’m from a touristy area, meaning the school’s social structure was almost environmentally wired against interlopers, shoobies, and fakes—people who would seek to claim ours (our beach, our locals-only jokes, our mini-golf courses) as theirs—a predisposition that extended to judgment of pretty much everyone on pretty much anything. This was the early 2000s, the golden age of the internet; it had been around long enough to be a reliable resource but was still an almost unfiltered frontier, filled with the sort of deep-cut knowledge of things that was once only accessible through in-person fan clubs and physical encyclopedias, now available with the right search string and the click of a button. Anyone could be an expert on anything instantly, if they knew where to look.

I always want to be well liked but, even moreso, I want to seem intelligent. I’ve learned to temper this as I’ve grown, but the mix of social pressure and adolescent emotions when I was in middle school meant that I, more often than not, was an absolutely insufferable know-it-all who frequently knew little. This was also around the time I was beginning my love affair with angsty music, and around the time Green Day released American Idiot. The album, though not a return to form (it was a starkly different album, structurally and sonically, than anything the band had ever released), was a return to popular acclaim. By early 2005, their slick guitar riffs and infectiously guttural vocals were almost literally inescapable. By all measures, they were successful; by fans’ measures, they had sold out. To have known them before they were famous, then, was a badge of honor; no one wanted to be a bandwagon fan who only heard of them from the “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” video.

The easiest way to fake your way to Green Day fandom was to profess love for songs from Dookie, which was, up until that point, their most popular and successful album (as well as the one that branded them as sellouts to their original California punk fans at 924 Gilman Street). “Longview” is now heralded as a standout from that early era of pop punk, and “Basket Case,” a track explicitly chronicling an adolescent breakdown and suburban ennui, still inspires scream-alongs whenever it’s played at the right audience. Dookie peaked at number one in 19 countries and eventually went diamond. It was also released in 1994; I was barely two years old when “When I Come Around” came around and ensured that Green Day had evolved from specters of California garages to fixtures at multinational franchised record stores.

But, thanks to the fact that we were all 12 when American Idiot was released, an album that was in fact mainstream to an adult fan seemed like a relic to those in my cohort. We had to seek it, or be told about it, or otherwise earn it through scouring Ask Jeeves results and primitive versions of Limewire. Instead of American Idiot, handed to us over the airwaves and on TRL, we had to work for Dookie, and being cool was the return on investment.

I had never heard of Green Day when American Idiot saturated the airwaves (outside of the few chords of “Good Riddance (Time of Your Life)” that inevitably played every so often on soft rock radio), but I wasn’t about to let anyone around me know that. I threw myself headlong into assuming jilted, wildly inaccurate authority on the band. I tried to wax poetic on Billy Joe’s lyrical intentions (missing the very specific and obvious political commentary entirely in favor of a personal narrative) as well as his personal life, and asserted that I knew the band’s history as if it were my own. This was betrayed when I, in relative private and trying to sound hip to my middle-aged mother, claimed that Green Day had been nominated for the Best New Artist Grammy, to which she replied, “Really? I thought they’ve been around for a while.”

There’s no way I was the only one trying to perform this hollow fanaticism. A boy I knew, aspiring to be a rock star with rudimentary bass playing abilities made up for with a killer smile and requisite floppy hair, would frequently post rock lyrics as his AIM away messages. Some were accredited to their actual writers or performers, but more often than not, he’d sign them with his “stage name,” perhaps innocuously, but nevertheless to the effect of passing them off as his own, including the chorus to “When I Come Around.” Because the song was a megahit instilled in the annals of punk history and frequently spun on the radio, it eventually came on during gym class. Someone—either myself or a friend; mortification has ruined my memory of this moment—enthusiastically told our teacher, the coolest one at the school, that our classmate had written the song. She looked at us incredulously but nodded along anyway, giving us the baseless acknowledgement of our own coolness we had all been desperately reaching toward at the expense of the very thing we’d been using to build our cred in the first place, experiencing and knowing anything about Green Day.

It was only after time passed and I recognized that I was drawn to Dookie’s triumphantly irreverent but emotional type of music, a singularly insular, personal phenomenon, that I actually began to meaningfully listen to the album. Nothing hit me harder than “Basket Case”’s frenetic ownership of clearly unbridled mental illness. That track accomplishes an almost impossible feat: control of and amusement at an otherwise all-consuming, debilitating disease, all delivered with a wry attitude and punchy, unbothered guitar chords. In “Basket Case,” neuroticism is not a phantom but an annoying friend at the end of the lunch table; an ever-present companion you learn to live with publicly while privately trying to decode the impulses behind his idiotic shit. Though I did not have names for my various mental health issues as an early teen, their pressures and influences were something I could instantly recognize; hearing someone at once make peace with and minimize them, all while firing off some slick chords, felt like the world had opened up before me. Realizing that music, especially music so deeply entrenched as a status symbol, could be personal and resonant instead of just Cool, was revolutionary. I was spending more time falling down the Limewire rabbit hole and the “Listeners Also Purchased” lists on iTunes, but this time, it was relentless and insatiable and gleeful; this time, it was for me.

Parts of Dookie resonate with me still: the constant undercurrent of anxiety; youthful rebellion that is as electric as it is aimless; a longing for Something Different, almost inarticulable and all the more potent as a result. What stands out most, though, is the unshakeable sense that, under the cocksure and lackadaisical lyrics and garage-band-cool instrumentals, Green Day had no idea what they were doing. Nearly every song, from “Basket Case” to “Coming Clean,” deals with trying to find the Self and practically revels in the impossibility of that task. Dookie stares down the enormous pressure of identity and external perception and snarls in its face.

I don't actively listen to Green Day much anymore (a side effect of growing up and realizing that, for the most part, it is the sort of music middle schoolers would listen to to impress each other), but every so often, “Brain Stew” or “Basket Case” shuffles on while I’m walking home from work. Amidst the shadows of D.C.’s famously low skyline and below the signs for federal bureaus, I pump up the volume and let Billy Joe scream for a few minutes about what it’s like to be unmoored and unashamed of it. I slip back a decade and remember being 13, writing tremendously bad poetry about the drama at school and drama at home while a Green Day music video loops on my boxy TV set.

Do you have the time

To listen to me whine

About nothing and everything all at once?

I am one of those

Melodramatic fools

Neurotic to the bone

No doubt about it!

I headbang as undetectably as possible, I open Twitter, I fire off a self-effacing quip, and for a moment, I forget that the very legions of people and institutions I’m constantly trying to impress are literally watching me. I forget about being cool. I forget about any of it. It’s just me, alone with a song I know by heart.

—Moira McAvoy