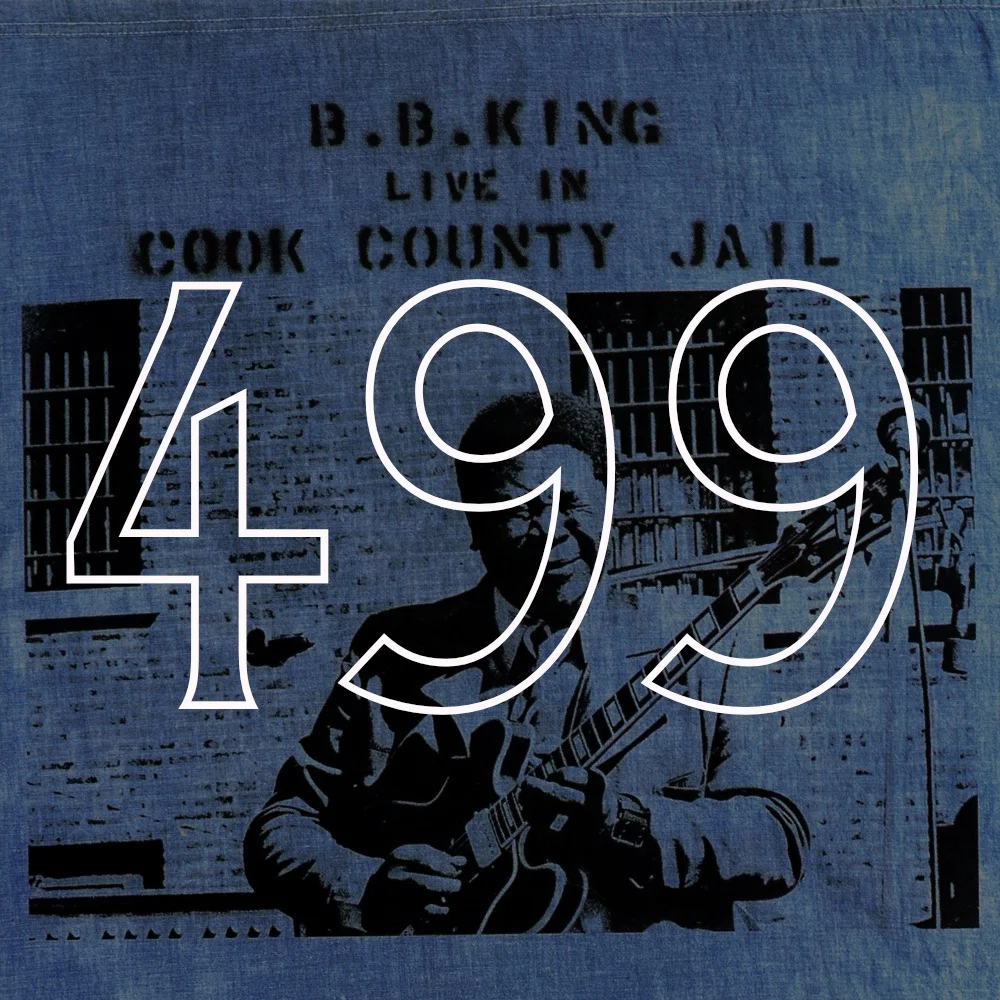

#499: B.B. King, "Live In Cook County Jail" (1971)

It is nearly 90 degrees in Southwest Chicago, too hot for September, and Jewel Lafontant waits in the long shade of a guard tower as the Cook County Jail Jazz Band rolls through the handful of standards deemed morally commendable by the warden. The yard is so large and filling so steadily with tired, buzzing, angry bodies that the rim of barbed wire strung across the high walls around her seems more like cotton candy than fine razor, hardly enough to hold anyone back should the wrong thoughts start brewing.

She fans herself, absentmindedly taps her foot to a respectable “A-Train,” and cranes her neck to get a better look at the tower whose shadow she’s so thanklessly exploiting. Brick and thick green glass. Steel and a few holes large enough only for a rifle muzzle. All angles and indifference, like a spaceship left to rust after some failed reconnaissance. The whole uncaring shape of it would make her shiver were it not so hot out in the open frying pan of the concrete jail yard.

Someone has called her name. She turns to see Joe Woods, Crooked Sheriff of Crook County, making his diligent way toward her. He looks worried but is smiling still, hand at the end of a starched white shirt, sleeve rolled once, jutting stiffly out. Miss Lafontant, he says, though he knows very well that she’s married. She bites her tongue, shakes his hand, says, Joe.

You ready? His eyes are half-empty, fatigued, still expectant somehow in their shallows.

Say the word. At the end of this day of waiting to be told by white men where to stand and when to speak, it’s all she can think to say. Tomorrow, she will be back in the office, poring over cases, making her own tough choices like she’s used to. Since being made vice chairman of the U.S. Advisory Commission on International, Educational and Cultural Affairs just last year—a whole lot of big words for too many stuffy meetings, not enough action—she’s been half-seriously waiting for a call from the president himself any day now. And word is Nixon’s got her in mind for the Big Bench itself, first black woman in the Supreme Court. Wasn’t too long ago she was the first ever to make a case before them, and now there are whispers of her joining the brood. Look how important she’s become, how hard she’s worked to get here. Look how proud she’s made her mama.

But today she stands in the high 90-degree sun and waits to take to a makeshift plywood stage to introduce a middle-aged bluesman in the yard of the Cook County Jail, an institution Ebony has just anointed the “World’s Worst.” She knows King’s music, of course. Even before “Thrill,” before all the hoopla. It reminds her of her father: all that growling, slick danger awash in sensuality. Dirty and familiar, all at once. Repugnant and strangely alluring. She’d be the last to admit it, but she’s spent more than her share of nights alone swaying, brandy-blushed, to heartbroke black bluesmen, Mr. King certainly among them.

Now half an hour ago she met him in the bright administrative halls beyond the cellblock, and he certainly was charming. Very gracious to make her acquaintance and all that. She always liked a man who went to shake her hand rather than kiss it.

And here’s Joe again, sunglasses reflecting her stony visage back to her. He is signaling her to the stage. Showtime; she walks.

Standing before the rows of seated convicts comes natural to her, and speaking to a crowd’s no different. With the band all set up behind her—all but B.B., swaying softly from foot to foot just behind the risers—she feels like a bonafide musician for just a moment. Like she could take the microphone from its stand, coil it around her wrist like she’s seen Diana Ross do, and launch right into “Where Did Our Love Go.” Or, no. Make the piggies sweat. “Strange Fruit.” She smiles, more broadly than she’d planned.

Hello out there, she begins, testing the mic’s sensitivity. We’re about ready to begin our program. It’s a beautiful day in Chicago, and we’re going to have a wonderful time this afternoon. Lying through her teeth. What “beautiful day” have these shackled people, mostly black, mostly sneering or staring motionless at the lawn directly before them, ever seen? What “wonderful time” was ever theirs to know?

She gets through the obligatory acknowledgements to Joes Woods and Power, the latter without a doubt her least favorite judge in the county. The inmates boo loudly, drowning her out at the mention of each man’s name. The red-faced guards’ faces get redder, their hands moving quickly to the tools on their wide waistbands. Jewel stands unfazed, even laughs a little. All this for some music, she thinks, and waits for them to finish.

Now, B.B. King is known to everyone as the king of the blues, she continues. He’s been referred to as the Chairman of the Board of all the blues singers. He’s been called the man. She’s getting into it now, revving the prisoners like an engine, doing what she does best. Eye contact, attorney’s conviction, all that. But whatever we call him, I know him to be just a fine, warm human being full of humility. She grins even wider, nods as if in reverence, laying it on as thick as she knows how. Then she turns to the guitar player waiting at the stage’s edge. Would you please come forth, Mr. King?

And she steps aside, relinquishes the afternoon to electric live music: blistering speed-play, a rhythm section not even breaking a sweat in keeping up with the Chairman’s fingerwork. The blues played this way, in this heat, for this crowd? She has to work against its magnetic tide herself, sure it will be enough to incite a riot. She hopes the guards are as dangerous as they look.

It isn’t until twenty minutes into the set that the music slows into a steady twelve-bar groove and the bluesman swings his guitar out of the way. He rips the microphone from its stand and starts to pace and preach. All flop-sweat and righteous conviction.

Ladies, he says, and when the first few rows of inmates respond hungrily, it’s the first time Jewel even notices there are female prisoners in attendance. Ladies, if you got a man, King continues, and the man don’t do like you think he should, don’t you hurt him. And then, as though deeply dissatisfied by the crowd’s lackluster response, he shouts it, guttural and mean: I said, don’t you hurt him!

Jewel’s moved to the side of the stage now, and she can see his eyes, black and leveled and drilling his audience with pure conviction. This is not the warm, humble man she thought she’d introduced. In his place now is a different man entirely, one who seems to be speaking directly to her in the same voice she’s been hearing all her life when he says, Man happen to be god’s gift to woman!

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

She’s hit with the sudden realization that though he might be preaching, this man’s god is certainly not her own. His is twisted, outdated. His face now the stricken, ugly one of someone who’d rather forget the sixties ever happened. In a flash, she sees her father again, but this time all the worst sides of him she thought she’d chosen to forget. The bitter postwar conservatism. The holding fast to old ideals.

But she seems to be the only one: what this man here has just said now gets the largest response from the crowd all day. Even the women in the front rows are cheering, clapping their hands wildly over their heads and nodding as if to say, Preach! Jewel has no other way to describe how she’s feeling except nauseated. It could be below freezing outside and at this very moment she’d still be a pot boiling swiftly over. Carouseling through her head come vivid portraits of every white judge in the district, every balding pate of every man sneering in uniform, every criminal blowing kisses at her even as she put him away. She feels the weight of the afternoon just listening to King go on. Another swindle. Another day.

In a half daze but still there enough to mind the way she must look to others, she looks calmly at her wristwatch before walking casual as anything back into the concrete compound, through the checkpoints, and into the sun on the other side of the prison walls. She knows she’s meant to thank the crowd and the band once the concert is done, but for now she’s very much undecided on the prospect of returning. She breathes in, chooses a direction without thinking, and walks until the music fades into her footsteps.

—Brad Efford