#208: Cat Stevens, "Tea for the Tillerman" (1970)

Side 1

1. Where Do the Children Play?

I know we’ve come a long way. We’re changing day to day…

I don’t go back there very often anymore. For one thing, it’s been more than forty years. For another, it’s still too close, still too near.

It’s unseemly, I know, for a fifty-seven-year-old man to revisit—not as a fleeting sentimental excursion, but as a true time-traveler, a this-for-that, a now-for-then— the child he’d once been. There’s a great line by the songwriter Jason Molina, whose gloom-laden songs I adore: “Why put a new address,” he sings with his plaintive tremor, “on the same old loneliness?” In this case, I’m advancing the reverse of Molina’s rhetorical question: Why bother going back to that place where the loneliness started? Isn’t the here and now always enough of its own mess?

But we all do it, I suppose. There’s the comfort of that. We snake ourselves back through the years, touch the sore spots, the old bruises. We all had a first love, a first loss. It’s unlikely mine was any greater, any more profound. The only thing different for me, perhaps, than for some others is that mine broke—or broke loose?—something inside me, drew a fine jagged path beneath my skin like the lines in cracked porcelain, a delicate and beautiful damage that became for me, for years on end, the single greatest measure of my worth. I’ve put that feeling to fine use, I guess: it made me maybe a little less of an arrogant asshole than I would have been, and it made me a writer, which gave me a way back in, again and again, to the anguish I felt inside me, scrubbing away at the pain until its black patina wound up burnished, strangely glowing. Beauty and torment, forever aligned, forever wed.

2. Hard Headed Woman

Yes. Yes. Yes…

I am a grown man now, more father than son. I have received love in greater measure than I have given. I have loved—and love still—my wife and children.

But I was a child once, so here’s the child’s story: At thirteen, I fell in love with a girl whose life was a match for my own: she was one of seven; I was one of eight. Our families were Catholic, our fathers both physicians, our mothers both (though very different, each in her own way) wrecks. We talked hour after hour, though not a word of what we said survives in memory. Sometimes we visited her sister in a psychiatric ward uptown; late on Friday nights we snuck into a friend’s father’s optometry shop—to smoke and drink, I suppose, but also to lay claim to this forbidden space.

Mostly, though, she and I sat cross-legged in her bedroom listening to 45s and LPs: James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, the Beatles, Cat Stevens. Oh, how we loved Cat Stevens. We worshiped his frail beauty, his haunting voice, his songs’ endless quest for enlightenment, for deliverance, for grace. She was an artist and made me a gift I treasured: the round Zen symbol from the album cover of Catch Bull at Four painted on a small wooden block. We found solace in each other amidst the awful vortex of adolescence and our fucked-up families. We learned something about desire and the longing for transcendence and escape. We learned it with Cat Stevens’ words echoing and echoing in our heads, telling us again and again that an arduous journey lay ahead but that pain would be followed by pleasure: If I find my hard-headed woman, I know the rest of my life will be blessed.

3. Wild World

Now that I’ve lost everything to you…

And that was it. She went away that summer, made some new friends, cooler—more exciting, more experienced, more dangerous—than she figured I could ever be, which I knew was true, which I knew was true with every fiber of my being—and the cracking began, the fissure opening bit by bit by bit.

4. Sad Lisa

Open your door, don’t hide in the dark…

It would be years before the word depression showed up in my life, decades before I knew myself well enough to use it, to know that this was what I suffered from, what would rise up again and again for the rest of my years on this earth no matter what doctors I talked to or treatment I endured or pills I took.

Back then, when my teenager’s heart was broken, I thought it was just sadness, thought I was just the sensitive romantic type who couldn’t get over this one girl, what she’d done. I didn’t yet know about the romantic poets, about Whitman, about Lorca and Rilke. I hadn’t encountered Keats and his wistfully suicidal melancholy:

Darkling I listen; and, for many a time

I have been half in love with easeful Death,

Call'd him soft names in many a mused rhyme,

To take into the air my quiet breath…

But I knew I wanted to dig that deep, and it was Tea for the Tillerman that reliably took me there, the lyrics printed on the album’s yellow and blue back cover, encircling a brooding portrait of Cat Stevens seated against a tree. He looked away from the camera, his hair a dark mane of curls, his beard sharp, somehow menacing. He was angry, forlorn, doomed. He was St. Sebastian, the crucified Christ, a mendicant, a hermit. He was lost.

5. Miles from Nowhere

I creep through the valleys and I grope through the woods…

I was lost. I stayed lost. I wandered hour after hour alone between the leafy cul de sacs of her neighborhood, through the ruins of an old Spanish fort, along the lakefront levee. I sat for hours on the concrete steps that led, inexplicably, down into the water, as if inviting me to wander in. I wrote in notebooks, wrote poems, told myself I’d use all of what I felt some day, make something remarkable from it, some kind of testament to—what? I didn’t know, couldn’t find the words for it. I went back to my life, spun forward through the years, one girlfriend and the next, high school and college, but the feeling never left me, never quit. I stayed lost.

Side 2

1. But I Might Die Tonight

To say yes or sink low…

I was just a kid. Then I wasn’t.

Cat Stevens had been a kid, too, I realize now. Most folks know the story: a twenty-one-year-old British pop star laid low by tuberculosis, reemerging after a lengthy convalescence as an introspective troubadour, producing a series of remarkable albums that brought him worldwide acclaim: Mona Bone Jakon, Tea for the Tillerman, Teaser and the Firecat, Catch Bull at Four. He made more albums after that—I loved Foreigner, tried to love Buddha and the Chocolate Box—but he struggled, as artists do, to be both brilliant and famous, to be content with what he’d done. In 1978, having converted to Islam and changed his name, he renounced his music career and disappeared from view.

I remember when it happened, remember how unsurprised I was, how it seemed the perfectly predictable culmination of all the searching he’d done. You wander long enough, and you’re likely to end up in a place from which you can’t return or don’t want to. Cat Stevens hadn’t been his real name. He’d been born Steven Demetre Georgiou, had performed first as Steve Adams, had chosen “Cat” because, he said, his girlfriend had a cat, because he figured people liked animals.

He’d never been who he was, I figured.

2. Longer Boats

Oh how a flower grows…

It took me years and years, but I did what I set out to do: I created stories that tried to name the unnamable sorrow that had split me open. By doing so, I discovered that the source of such despair is, of course, much more fundamental, much more nuanced and complex, than the child I’d been had assumed. Sadness hadn’t overtaken me because of adolescent heartbreak. That had merely been the spark for something larger, something patiently waiting inside me—waiting, I suppose, for life to leave its mark.

So I set about imagining families ruined by shame and silence, men tormented by longing, children abandoned and bereft, mothers so badly damaged they are incapable of love, fathers who disappear, sons who, forsaken, forsake and flee as well. I wrote and wrote and wrote.

Lo and behold, life brought me joy: a beautiful wife, beautiful children. A good life. I am so deeply grateful.

3. Into White

I built my house from barley rice…

It never leaves you, though. You can never do enough to fully set the feeling aside. Just about everyone with depression will tell you this: you live with it.

4. On the Road to Find Out

In the end I'll know, but on the way I wonder…

You live through it, it seems to me. Depression is as much of a lens as it is a weight. It makes it hard to be certain about anything, to think you know how you actually feel, to feel you know how you actually think. You’re forever wandering, forever lost, inching your way forward, hands out, cautious—or else you’re falling.

The fall is often precipitous. The well is—or can be—deep.

And the well can disappear, can become the air, the falling become flight, a monumental feat of majestic soaring.

5. Father and Son

Look at me, I am old, but I'm happy…

I imagine Cat Stevens never imagined, not really, that one day he’d be old enough to sing the father’s words more authentically, closer to the bone, than those of the son. But here he is now, his music career heartily resumed as Yusuf, a sixty-nine-year-old graybeard confidently strumming, singing: It’s not time to make a change. Just relax. Take it easy.

Away. Away. I don’t believe it. Not completely. It often seems to me that we are always closer to the sons we once were than the fathers we’ve become. What plucked or scraped or tore at us all those years ago remains forever at hand.

6. Tea for the Tillerman

Oh Lord, how they play and play

For that happy day, for that happy day…

But what do I know? I’m just an old man, or nearly so. I make my coffee in the morning, slowly climb the stairs to my study, and sit down to fight the same quiet, unceasing battles: to make something beautiful, something lasting and good, from my life, to steer clear of the darkness, to find and follow the light.

I still don’t know when or why I’ll be laid low, any more than I know how that pain gets transformed into art, that art into joy, that joy into life—

which goes on.

The sinners sin; the children play.

—John Gregory Brown

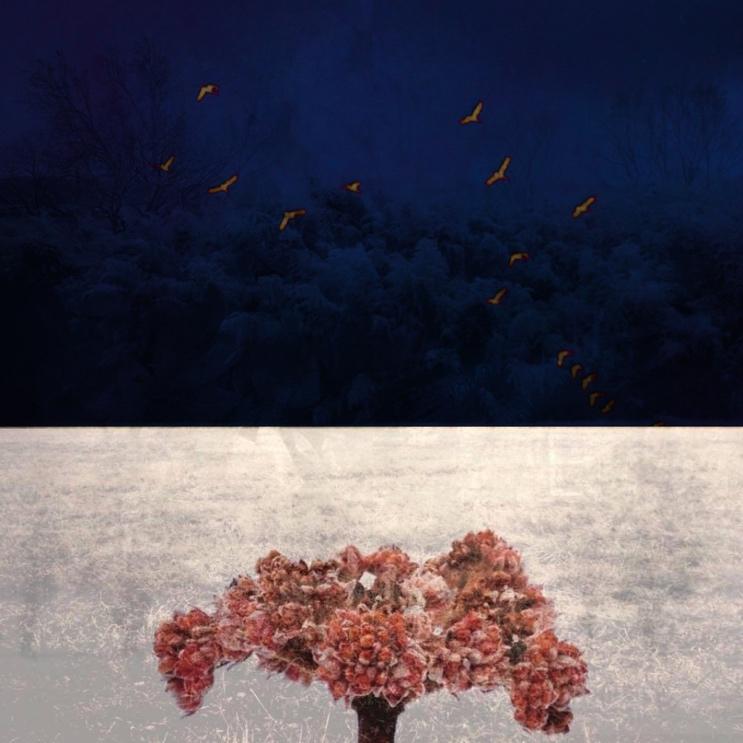

All artwork by John Gregory Brown