#233: The Byrds, "Mr. Tambourine Man" (1965)

The climax of discomfort for me at Robinson Secondary was the middle school dances, where we crammed into a cafeteria with censored pop playing from a carpeted stage. I stayed in a cluster of my three loyal friends. My three loyal friends, who wore rhinestones on Limited Too T-shirts and wrote Buffy the Vampire Slayer fanfiction in their rooms late at night. I jumped up and down to music, my hair frizzing from the collective body heat of grinding 8th graders. Someone always said, “Watch it! Your ponytail just hit my face!” I was so relieved when the lights flicked on and the cafeteria was fluorescent-bright and safe again, telling us it was time to go home.

Middle school was a tedious and self-conscious two years. It was then that I entered a phase. I became fascinated with the 1960s and 70s. The phase came from a perfect storm of places. One: I noticed our U.S. History syllabus always stopped at the end of World War II (“Not surprising,” my dad would say), which gave the following decades a certain mystique. Two: I discovered a Polaroid album of my parents from high school. The album included a photo of my dad hanging upside down from a basketball hoop with an afro of brown curls, and another of my mom with sun-bleached hair down to her elbows, leaning against a door frame with her eyes shut, and smiling. I studied the album many times, the glue in its binding cracking every time it was reopened.

My 60s-70s fascination was fueled when my dad bought a clunky VHS set from the History Channel. Every video featured a different decade. One night I reached for the unexplained decades, the skimmed-over, disappearing pages of my public school education: 1960-1969 and 1970-1979. That night in my bedroom, I watched America revolt and explode from the prim, bubblegum early 60s to full revolution. I watched young soldiers wading through swampy grasses and students walking out of classes to march on their campuses. I was moved by the magnitude of change. I rewound the footage and watched again. Middle school felt very insignificant.

“What do you want for Christmas?” my parents asked me that year.

“I want all your favorite albums from when you were growing up.”

“That’s what you want?”

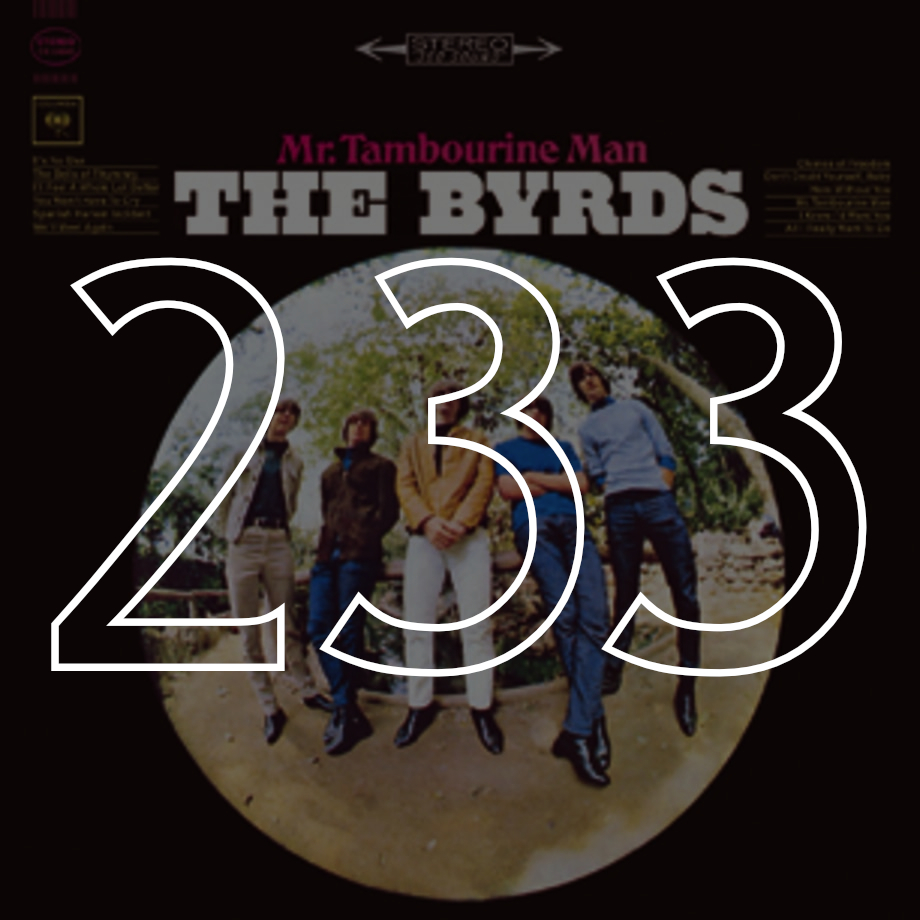

On Christmas morning my strange request was met. I was given two stacks of my parents’ favorite albums, each cover with bell-bottomed, hazy-faced singers. There was nothing hot and edgy about them. As my parents interrupted each other to defend their favorite albums, I doubted my Christmas present (all morning: “Really! You’ve never heard of Crosby, Stills & Young?” “I don’t think so.” “Just stunning harmonies.”). One day my dad told me to listen to the song “Mr. Tambourine Man” from the Byrds album of the same name. I sat in front of my bedroom stereo and listened. I didn’t even know what it was about, but the melody rose and fell in me in the best, most bittersweet way.

The Byrds were campy and harmonious, somewhere in between the sugary early 60s and the rock to come. They felt unthreatening. The DJ-scratching, sexualized pop of middle school dances made me feel false as I sang, “SO take off all your CLOTHES!” I started to bring my Walkman to middle school, playing my parents’ music in my ears, so that I was protected in a sort of time bubble of the History Channel decades: 1960-1969, 1970-1979. “I wish I lived in the 60s,” I told my dad once. “Things were actually happening. I wish I was a part of something big.” I was corrected. He told me the country was a divided mess, and I wouldn’t want to live in a time like that. Fifteen years after that conversation, I’m sitting in a time just like that—a hot, divided mess.

Eventually, I stopped listening on repeat to the albums my parents gave me, as I learned to discover the music happening around me. But while the phase continued, I nagged my parents for frontline stories of social upheaval: “Did you go to protests??!” “No, not really.” “But was it crazy?!” My parents weren’t as interested in sharing stories about marches and flag burnings. They wanted to tell us about the time they went skinny dipping in the neighborhood pool with all their friends and almost got arrested. How the cops shone the flashlight at their best friend, the moment he was jumping nude on the high dive. Or the time they threw rolls of toilet paper around a rival school, and ran away into the woods as the sirens came. They told these stories again and again, interrupting each other, laughing until crying. I envied them and their stories.

My parents, unlike me, had lived fully in their school worlds, the national turbulence a blurry background behind their first loves and friendships. Meanwhile, I sought escape into history, into music that nobody was listening to anymore in the 8th grade. When my parents didn’t indulge my fascination with the past, I came back to my Christmas gift albums—the homesick folk, the sunny California Byrds, the croaky, raw Dylan. What I didn’t know then was that things were happening in my time, things worth fighting for and writing music about. I just didn’t know how to be a part of it yet.

—Rachel Mason