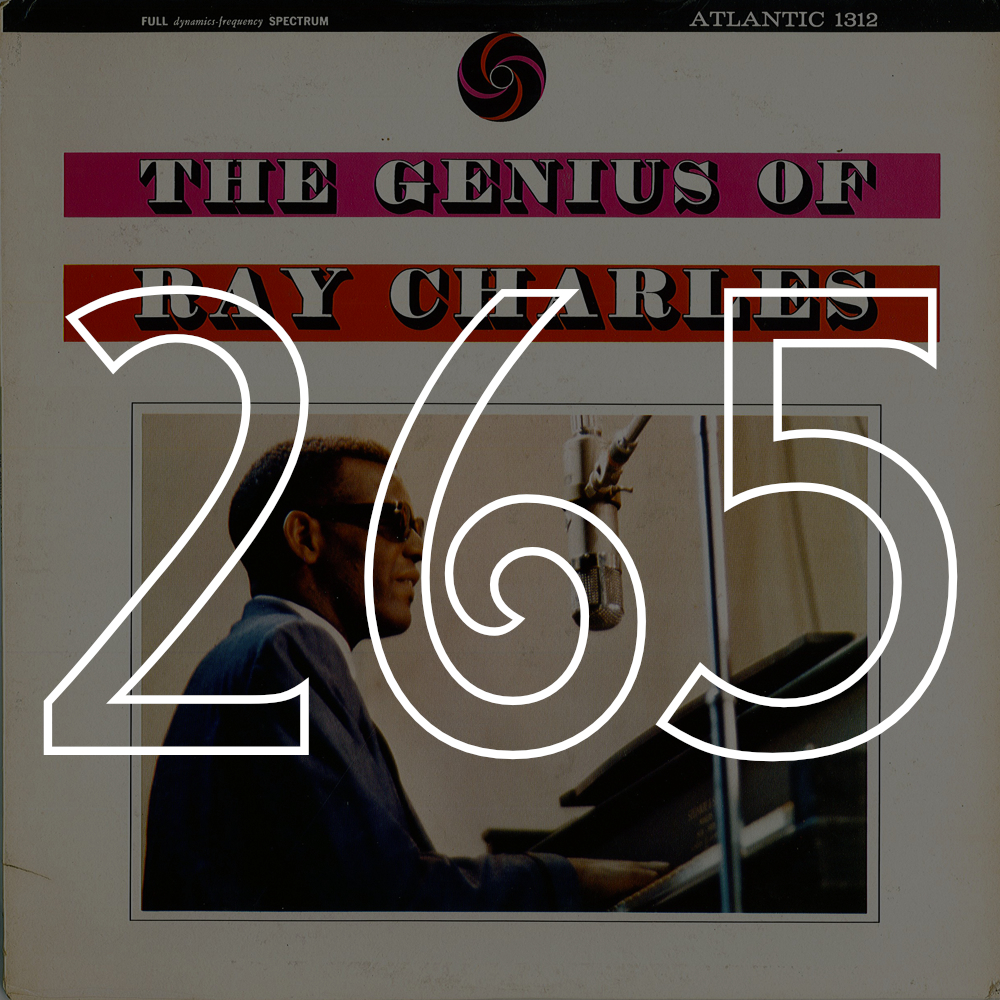

#265: Ray Charles, "The Genius of Ray Charles" (1959)

It was his city rendered strange, become track, become route, the footfall-by-footfall measuring of effort. 26.2 miles of city streets were blocked off for the runners, and Joe found himself at mile 18 running in the early spring rain by the Pennsylvania Avenue entrance to his own old neighborhood, through an intersection where he had sat countless early mornings smoking cigarettes in his car and cranking the rock to get him up for the day. Now he glided past, fleet and quiet on the outside, his body aching and Ray Charles belting “Let the Good Times Roll” in his ears: “Hey everybody! Let's have some fun / You only live but once / And when you're dead you're done / So let the good times roll—.”

He opened an energy pack and tried to squeeze the gel down his throat, found both the gel and his saliva thickened by the cold air, his hands numb and hard to move. Mile 18 was always the hardest. When he had first started running, he listened to rock, the harder the better, the louder the better, operating under the assumption that the music would push him, energize him, back when running five miles seemed like an unattainable goal. But at some point he had realized that the narrative nature of songs, the egotistical first person of them all, kept him in a place in his head that disallowed the flow his mind was trying to drop into. The flow, that slipstream of mind and body governed by breath, feet, inhalation and exhalation—the flow wanted some other kind of music. Classical worked, and he had spent countless hours over the last few years running to Beethoven’s 9th and to the Goldberg Variations, Glenn Gould’s precision speediness inspiring a physical parallel in his own clicking pace.

Still, sometimes you needed a voice, you needed the murmur of sympathy in your own throat reaching for something past personality. Who had turned him on to Ray Charles? The way this marathon made his city not his city, but a meditative, testing route with a medal at the end, a proud sticker for his car, and a bright rayon T-shirt, Ray Charles wove love and longing into the formal properties of his songs, ropes of sound Joe wore like a scarf around his neck on this chilly day. He’d been a fan since he could remember. By the time that biopic starring Jamie Foxx came out, he had felt like Ray Charles was an old ally. He remembered going into the theater with a skeptical air, feeling protective of Ray and doubtful the film could get him right.

Why did he feel that way? Was there a moment before he knew who Ray Charles was? The rain was really coming down, worsening his need to pee somehow. He rounded the corner of Northwest Expressway, the empty early morning parking lot of Penn Square Mall sprawled before him, and he remembered his great-grandmother in her 1972 Cadillac, burgundy with gold trim, driving him and his father somewhere when Joe was small. What an aggressive driver—she’d driven a cab through the mixing bowl of Houston in the ‘60s, taking scientists to and from Cape Canaveral and drunk oil workers from bar to bar along the western rim, making more of her job than should have been possible, building a regular clientele and creating, in her cab, an environment of good tunes and strong drinks that people came looking for the way you frequent certain bars for particular atmospheres. The day Joe remembered in her Cadillac, she’d been driving with big, black shades on, the kind that wrapped around from ear-to-ear in a sheath of blackness. What was it, the incongruity of her delicate feminine features against the mobsterish shades, that had made him and his dad laugh? Something like that, something so tough and ready in the way she gripped the wheel and stared through opaque glasses at the bright day outside, had made Joe’s dad say, “You look like Ray Charles.” Joe hadn’t known who that was, Ray Charles, but his grandmother had affected a broad grin and tilted her head back, swaying her head side-to-side in a gesture that Joe understood to be an imitation of a blind person. His great-grandmother played air-piano against her steering wheel and belted out:

“Don't let the sun catch you cryin'

The night's the time for all your tears—”

Joe had been confused because he had heard her sing that song countless times and had thought it was her own composition, only understanding in that moment that she was singing someone else’s song. The Genius of Ray Charles, she had offered then, was his best, her favorite, the one she played most on the 8-track in her cab. It was big band, it was ballads, it was big-souled and it was slick as glass, pure professionalism powered by an artist simply manifesting who he was. His great-grandmother said those things; she talked like that, of band and soul and slick, and Joe had noted the admiration in her voice when she spoke of people doing what they were supposed to do and doing it well. He knew she felt she hadn’t done that well, herself, felt her life was too small for her, and so her Ray Charles imitation, her too-white dentures flashing, was more than mirth, it was a small act of becoming.

He had run marathons in cities he didn’t know, and it was better that way. This route was too familiar. He knew what was coming, with painstaking detail—hospital, gym, Beverly’s Pancake House, Starbucks. The route would head back downtown, ending where it had begun, at the Murrah Bombing Memorial. He would feel a rush of pride, civic and personal, when he saw it ahead, he would feel like he had done something good for his city when he pushed through the finish line, but in the meantime—what was the phrase?—in the meantime it was a mean time. His lungs burned. Other runners thudded around him. The toes of his right foot were tingling with needle-like pain, which meant his ruptured disc was acting up, shooting nerve pain through his extremities. A neon flashing signal that he really should stop. The rain chilled the early morning air and loosened all the grease and dirt on the road, making it slick and filling the air with the unwholesome smell of petroleum products. Which seemed right. This was an oil town, after all. What else should coat the roads? He really had to pee. A bright bloom of discomfort shot through his bladder with the strobing frequency of each step.

What was all this effort for? He wanted the city to vanish in a vapor behind him as his feet cleared each spot of pavement. He wanted to look back and see open plains where his hometown had been. Why did she have to go the way she went? And his dad—him too. Everyone in that old Cadillac was gone but him. He had the Cadillac. It sat in his driveway under a tarp, his grandmother’s tape player still in it, together with stacks of cassettes, their miniaturized copies of the album covers pasted to their plastic fronts. The Genius of Ray Charles was in there somewhere. But also out here with him, in his ears, out on the road, in the rain.

“Almost there!” A passing pair of runners called out, shot him waves as they crossed the nearly-empty road ahead of him. “Come Rain or Come Shine” was playing. “I'm gonna love you, like nobody's loved you / Come rain or come shine / High as a mountain, deep as a river / Come rain or come shine—”

He peed. Felt heat in his crotch, against his legs. Why not? He was pouring sweat; it was pouring rain; who would know? Because it was that or stop and ruin his finish time and he wasn’t stopping, he was going on. Like Alexander’s ragtime saints in the song, like the road and the city and the music, he was one of the things that was still here.

—Constance Squires