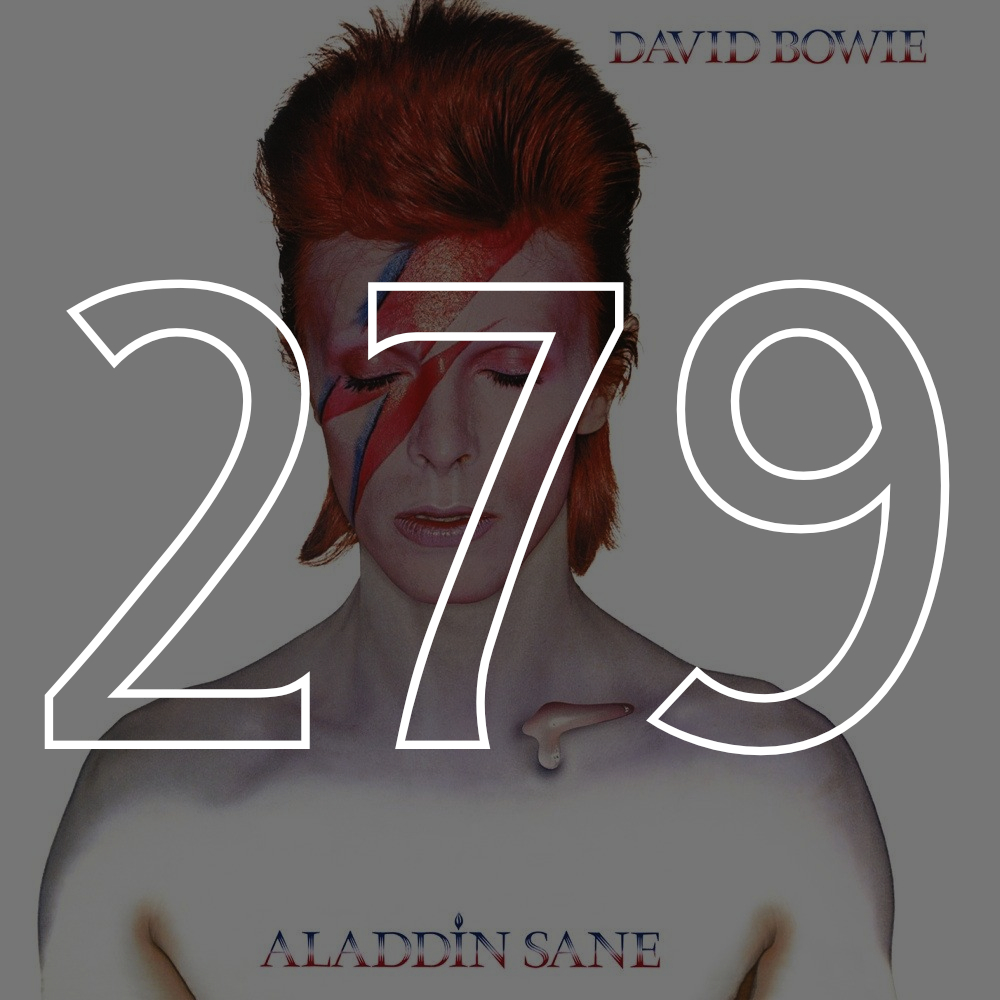

#279: David Bowie, "Aladdin Sane" (1973)

The storm’s slowing inland, like a semi truck hitting the steep, hard-packed slope of a down-grade’s emergency pull-off. In the delirium of dark and rain made mirror by the rental car’s windshield wipers and oncoming headlights, I blindly thumb through my Amazon Cloud player for anything that will keep me awake, that can provide a backbeat to the rock-a-bye of the wind gusts rising out of the Shenandoah. I type bo by muscle memory so I can toggle between Bob and Bowie. No sleep with a voice nasal-y and fast talking, I think I’ll call it America, I said as we hit land; no sleep in the heaviest of Bowie’s albums, oh honey, watch that man.

I’m driving back to New Jersey from Lena and Brad’s wedding in Harrisonburg, Virginia, to which I’d driven that morning—five hours down, five hours up. I wanted to stay, wanted to have another whiskey ginger and join the dance floor, but I have a reading tomorrow in Newark I can’t miss, and much grading to do besides. My thoughts seem like the flat line of a heart monitor, a beaded break sliding across the screen. I’m worn out from weeks of travel and work. A few weeks ago, at my gate in Minneapolis, I told a guy that I liked his hat, a black baseball cap with the cross-stitched image of Ziggy Stardust from the cover of Aladdin Sane, red and blue lightning homespun in heavy thread, orange-red mullet, the sharp cheeks, eyes downcast.

“Thanks,” the guy said, smiling as he turned to see who’d spoken. I caught his eyes’ movements, their gaze mirrored in shape by the scar on my cheek, right eye to jawline.

I moved forward, as if my zone had been called.

I’ve been traveling alone a lot lately, on trains and planes and rental cars. I like the me that travels alone, the one that leaves behind my husband at home, my dog, the dirty dishes, the laundry, a couple changes of clothes stuffed in a duffel bag, earbuds in, an order of two coffees from the flight attendant’s cart. In-laws have often made comments about the fact that I travel on my own, that I’m the wife that leaves her husband alone. “Where’s J. at?” my mother-in-law says of a picture of me and a friend in a new city.

Recently, while hiking with my husband along a steep trail beside the Musconetcong River, we passed a young woman, out for a hike alone. It was deep on the trail, way back from the road. We told her hello, and she said hello back, her eyes scanning everyone and everything. After she was out of range, I told J. that I would never do that, never go out into the woods alone.

“I would be worried if you did,” he says, tugging our dog away from some deer scat.

My father, a forensic scientist and former cop, lectured me throughout my childhood about the dangers of girls and women going out on their own. He told me which way to twist an attacker’s wrist, to kick the backs of their knees, use fingernails on their eyes, “and don’t be afraid to give them a hard kick to their privates.” Not until recently did I ever realize what an impact these early lectures had on me and the way I move in the world, the way I avoid being truly alone away from help or streetlights or a phone.

J. once gave me pepper spray to keep on my keychain—I think it was a stocking stuffer. After a while, even though I lived in a city and rode my bicycle to and from the campus where I worked, I stopped carrying it, as if it was an invitation to try me, and I started meeting every man’s eyes as I passed him. I started telling them “hello.”

I’m not sure what changed in me, why I felt this would keep me safe, why I took the risk of not having a defensive weapon. I remembered then something else my father said, that I should never show fear—that is, weakness—in public. Stay alert. Show that you will remember a face, that you will remember who they are, if something ever happens. Traveling alone, although not a hike in the woods, allows me to be in public, in the world as myself, not a woman, a vulnerable target, a person with somewhere to go.

I buzzed my hair off after I was clear of cancer, in part because I was still so afraid it would return and, also, because I’d been so afraid that I would lose my hair in chemo, back when the doctors thought I’d have to go through a few rounds. Thankfully, the biopsy from the third excisive surgery of my cheek let me off the hook of chemo. By buzzing it later, when I was “okay,” or as well as the aftershocks of the anxiety and trauma would allow me to be, I was able to take ownership over my body, a body that had felt de-sexualized, some days even gender-less, when I was sick.

When I went out with my husband to supper, servers often called me “sir” when they walked up behind me. I wasn’t offended. It was like having someone hurl a pebble at me when I was standing behind tempered glass. In some ways, it was the most respect I’ve ever received from strangers in public.

“Aren’t you afraid people will think you’re a lesbian?” a hairdresser asked me candidly.

“So what if they do—there’s nothing wrong with that. Plus, it’s none of their business,” I said, and she didn’t reply, but I could tell in the mirror by the way she studied the hair clumping up like bales of hay before falling to the floor that she was worried for me.

On Twitter, I say something about how triggering the news is about Donald Tr*mp’s sexual misconduct, and a rando responds that I’m just jealous that he didn’t rape me and that no one would ever “consider me” because I look like a “little feminazi.”

A female friend types to me, “feminazis unite!” but even that hits me the wrong way. The word further problematizes feminism, connecting it to Nazism. I block the rando, close my computer, and go to bed.

Near Grimes, Pennsylvania, a marquee reads:

GOD UNIQUELY & LOVINGLY

CREATED YOU

TRANSGENDER IS HUMANISM

There’s a telephone number beneath the message, and I wonder who would answer if I called. I’m surprised to see the sign, even though I don’t quite follow its meaning and fear that it has been defaced from “TRANSGENDER IS DEHUMANISM,” since I’m in a part of the country littered with “BLUE LIVES MATTER” and “TR*MP PENCE 2016” signs. If it is as I fear, I wonder if the argument is that God created each person as a specific gender and, therefore, one shouldn’t try to change it. If it isn’t, if it is in support of trans individuals, it’s suggesting that it’s God’s intention to create each individual’s unique gender identity. I hope it’s the latter.

Every time I travel, I lose myself in my head and almost forget that I have a body, except when my hips begin to ache from sitting at the wheel all day or my feet start to swell from a cross-country flight. Tonight, my body reveals itself only in its sleepiness. I’m uncertain if the bodily disconnect is a good or a bad thing, something I should want, something I should even need. Do we need the mercy of being relieved from our bodies sometimes? Does you mean the you I understand myself to be, or the you that others see me as, a body?

When I was a kid, I used to play in drag all the time. I wanted to have all the boys’ roles in playtime: father, sheriff, cavalry general. I wore baseball caps so often that my softball coach called me “The Hat,” and my mother once had to make me a giant fake beard out of felt and brown-dyed cotton balls and elastic so I could wear it for a book report at school. I wouldn’t let my mother refer to my underwear as “panties,” and I loathed the thought of ever having a period or wearing a bra or buying makeup. I hated the color pink and I detested princesses, because I saw them as weak. In truth, I saw all things “feminine” as inferior to explorers and scientists and doctors and cowboys (all of which I envisioned as male) because women didn’t seem to have any agency in their lives, in the world. It wasn’t until I hit puberty that I began to pay attention to, even see value in things I thought were “for girls.” (Estrogen, man.) My feminism seems to have an antecedent in my tomboyishness, in that play-drag. Although I identify as a woman, I want to complicate what that means, how being a woman sometimes means embracing feelings and expressions of masculinity, or what some often think of as “masculine.”

When I became sick, I retreated into those early feelings of gender-inbetweenness, in part, I believe, because I wanted to recover my agency, or at the very least to signal to the world that I didn’t have any agency as a woman over my sickness. My melanoma was sexless, genderless, and it had control over me, my body and possibly my death, as well as my thoughts. It said, hide in yourself, girl. Change who you are and maybe it won’t recognize you.

But accompanying these feelings were the comments—from friends and strangers alike—about the scar that shifted and changed and redrew itself across my face with every surgery. “What’s the other guy look like?” our house mover joked, as if I was one “guy” and I’d been in a roadhouse knife fight with some biker.

A nurse once said, “Once it heals, it will become less noticeable, more feminine looking.”

“Think of it as a beauty mark,” someone else said, without my query.

Although I temporarily felt less feminine, I didn’t feel as if I had gained any agency; I just felt dehumanized. I was the somebody that something had happened to.

It took months, even a few years, before I began to regain a sense of myself as something beyond the cancer, something not defined by it. In doing so, and through therapy, I learned to honor all of me, the androgyny of my mind and my trauma, the way some days I still need to find myself not woman, just me.

—Emilia Phillips