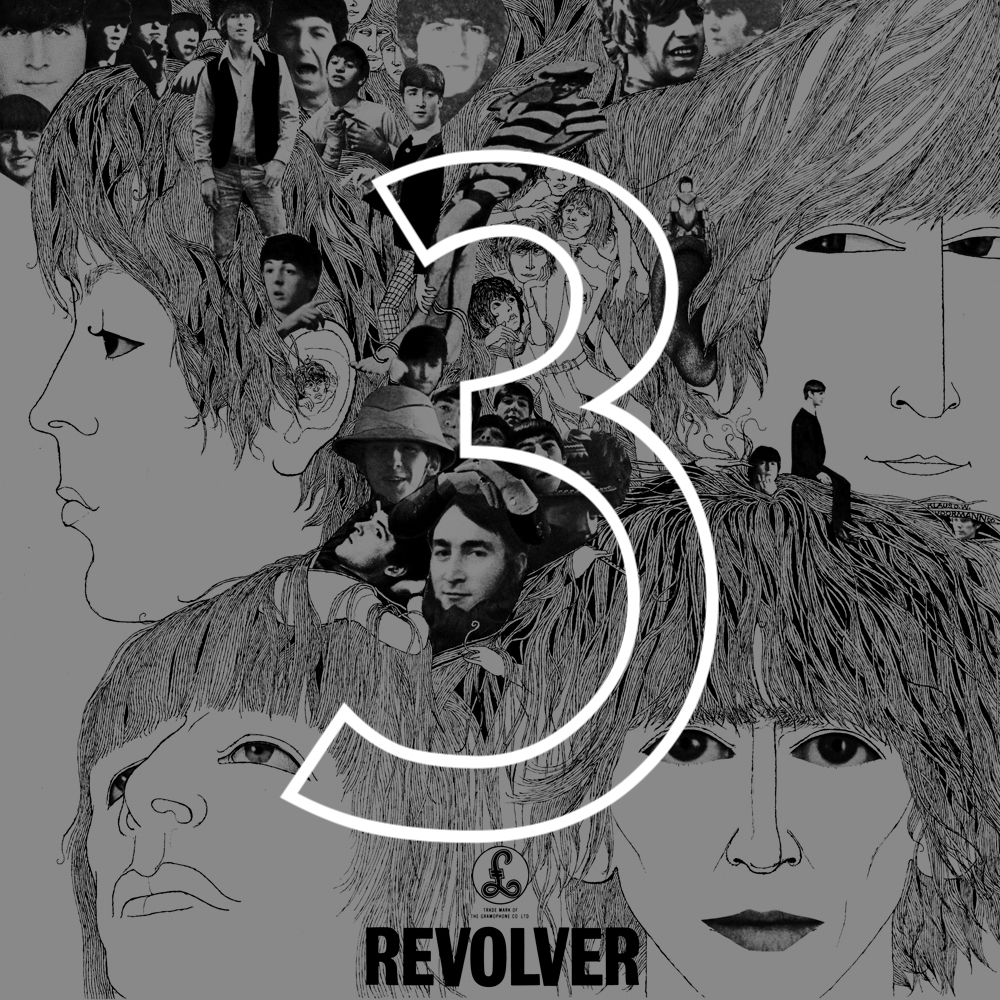

#3: The Beatles, "Revolver" (1966)

The dog has always been good at the vet. While the doctor and I talk, he sniffs around the examination room, looking at her occasionally to see if she’ll give him a treat like she usually does at the end of his visits. He might remember that from a previous visit, he might not. He’s almost fourteen and sometimes it seems like he doesn’t remember things as well as he used to.

I run through the list of my concerns. He slips on the stairs sometimes. We seem to surprise him sometimes. He doesn’t seem to hear as well. He’s lost a few teeth. Are his hips ok? Sometimes he takes a while to stand up.

The vet nods at all my concerns and tells me it’s all pretty normal at his age, and that his vitals are good.

“Basically,” she says, “you have a healthy elderly dog. He’s doing well. He’s got a good, strong heart.” She turns to him. “You’re a good old guy, aren’t you? Let’s get you a treat.”

The dog wags his tail in agreement.

*

I’ve thought a lot lately about reaching one’s peak. I still can run a half-marathon in a decent time, and my overall cholesterol went down at my last physical. I’ve got tenure in a field where full-time jobs seem to vanish regularly, have published one book, almost done with another, working on the proposal for a third. I’ve been married for nearly eleven years and I still look at my wife and think oh, I do love her.

I also spend a lot of time in the past, mine and those of others. At low points, I worry that I’ll never have a stretch like I did in graduate school when everything clicked in my life, and I lived a life that felt effortless and productive in the most gratifying way. I think about how I didn’t appreciate what my body could do from the start, that it took so long to start using it in all the ways I could.

Just about every morning for the last dozen years, I’ve woken up and walked the dog. Years ago, we both woke up ready to go, bounding out the door to greet the day. Now, we both slowly check ourselves as we get out of bed, flexing our joints. I get the coffee maker set up and running, and he takes advantage of the short break to lie down for a bit, whereas once he stood and watched me until I was done.

We aren’t done, not by a long shot. No one’s on their deathbed. But I’m a relatively healthy middle-aged man and he’s a relatively healthy elderly dog, and you can read it in our faces.

*

In the ‘80s, my dad’s friend Randy made a series of cassettes for him of the Beatles’ discography so that we could listen to them without the risk of scratching my dad’s original vinyl. The seven cassettes held the entire output of the band in order, from Please Please Me on the first to Let It Be on the last.

The tapes were labeled BEATLES OMR, volumes one through seven. Years later, I realized that they came from the Original Master Recordings, but as a child, I called them “Oh, Mister.” Oh, Mister Volume I had the fun songs and Oh, Mister Volume VI had the songs that I skipped because they were scary, and one of the Oh, Misters had the 1963 Christmas fan club message tacked on the end to fill a few empty minutes.

Because of Randy and the Oh, Misters, I grew up with the UK versions of the Beatles—no Meet the Beatles, no Yesterday and Today, and no version of Revolver that cut three songs, all by John. In our basement and in my room, I listened over and over to the original thing, growing up in the Midwest with a version of the album that my parents hadn’t had.

According to the metrics of the RS500, Revolver isn’t the Beatles’ peak; that’d be Sgt. Pepper’s, the next album, crowned by the Boomers as the Most Important Album ever. But Revolver is the most golden moment of the band, the time when the band is on fire at every second of the record. It’s that time in their career when they can do no wrong, when everything is going to fall into place for them because of course that’s what going to happen. They’re about to leave touring behind, the screaming crowds of girls and boys, and they can hear themselves. They have so much to say, too, after all of these years.

Every previous album started with a love song, but Revolver’s first three songs are about money, loneliness, and isolation. A song for kids precedes a song with the line “I know what it’s like to be dead.” The love songs are bitter (John, “And Your Bird Can Sing”), or disinterested (George, “If I Needed Someone,” “Love You To”), or the Greatest Love Songs They’ve Ever Written (Paul, “Here, There, and Everywhere,” “For No One”). Songs that sound like love songs turn out to be about drugs (“Got to Get You into My Life”) and songs that sound like drug songs turn out to be about love (“Good Day Sunshine”), or maybe vice versa. The whole album ends with a song so strange that decades later, Mad Men would use Don Draper’s befuddlement at it as a shorthand for the generational shift happening all around him—but then again, it turns out that “Tomorrow Never Knows” was the first song they recorded for the sessions.

Everyone’s playing out of their minds. Paul plays basslines like a man who knows he’ll never have to recreate them on stage. George embraces his love of Indian sounds while still writing songs inside that music, finding the sweet spot between the sitar accent of “Norwegian Wood” on the last album and the full-on “Within You Without You” of the next. John’s embraced the Nowhere Man he’s become and written songs that seem to get underneath his guarded persona; this is the guy who’s going to a show at the Indica Gallery in a few months and meet the woman to whom he’ll finally open himself. And Revolver is Ringo’s finest hour, the apotheosis of a drummer who could finally hear himself play. I’ve used Revolver as the response to anyone who tells me that Ringo’s a bad drummer. Ringo knows exactly what to play and when on every song.

So many gorgeous tiny moments in this: the yawn and the backwards guitar solo in “I’m Only Sleeping;” the way George and John’s backing vocals wind around Paul’s melody in “Here, There, and Everywhere,” never stopping through the entire song; the mysterious finger snaps that show up in the same song; Paul and George’s guitars driving “And Your Bird Can Sing” forward; Ringo’s giant drums filling up all the space at the bottom of “Tomorrow Never Knows.” They’ve got the studio time to explore, and they explore.

There’s no evident animosity, no tracks that sound like a band starting to disintegrate. All that will come later. Revolver’s sound is the sound of a band that knows it can’t do wrong, that the path forward is a path upward. It’s the sound of a band that has taken over the world and is now only trying to impress itself.

Is this a band that still wants to hold your hand? Sure, but they also want to explore the entirety of human consciousness and the universe. Not a big thing to ask of a listener.

*

If Sgt. Pepper is the Boomers’ Beatles album, then maybe Revolver is Generation X’s—at least in America, where the full British version didn’t appear until it was released on CD when we were teens. It’s an album about all our favorite themes—alienation and love, ambivalence and exploration, enthusiasm and ennui, and that feeling of being stuck between adult things like paying taxes and childhood memories of yellow submarines with our friends all aboard.

I don’t think it’s a generational thing, though—Revolver is an album for everyone. Sometimes I meet people who don’t like the Beatles, and I cannot understand it. Why deny yourself that joy of hearing those songs? Why pass up the chance to hear four boys who loved music and all happened to find each other in a depressed port city and wrote the best songs in the world? Revolver is an album to remind us that we’re all capable of greatness, of doing something and making it look effortless, of knowing both that the top is still ahead of us and that we’re going to reach it.

*

The dog and I are good today. He’s been happy all morning, smiling a gap-toothed grin at me when I pass by, and I’ve been able to work today with a momentum that I wish showed up more often. I’m going to finish this, and then ask him if he wants to go for a walk, and if he hears me—and he should—he’ll hop up, and we’ll head out into the sunshine, two guys on a good day.

Are we past our prime? Oh, Mister, who cares? I know an album that’ll help with that.

—Colin Rafferty