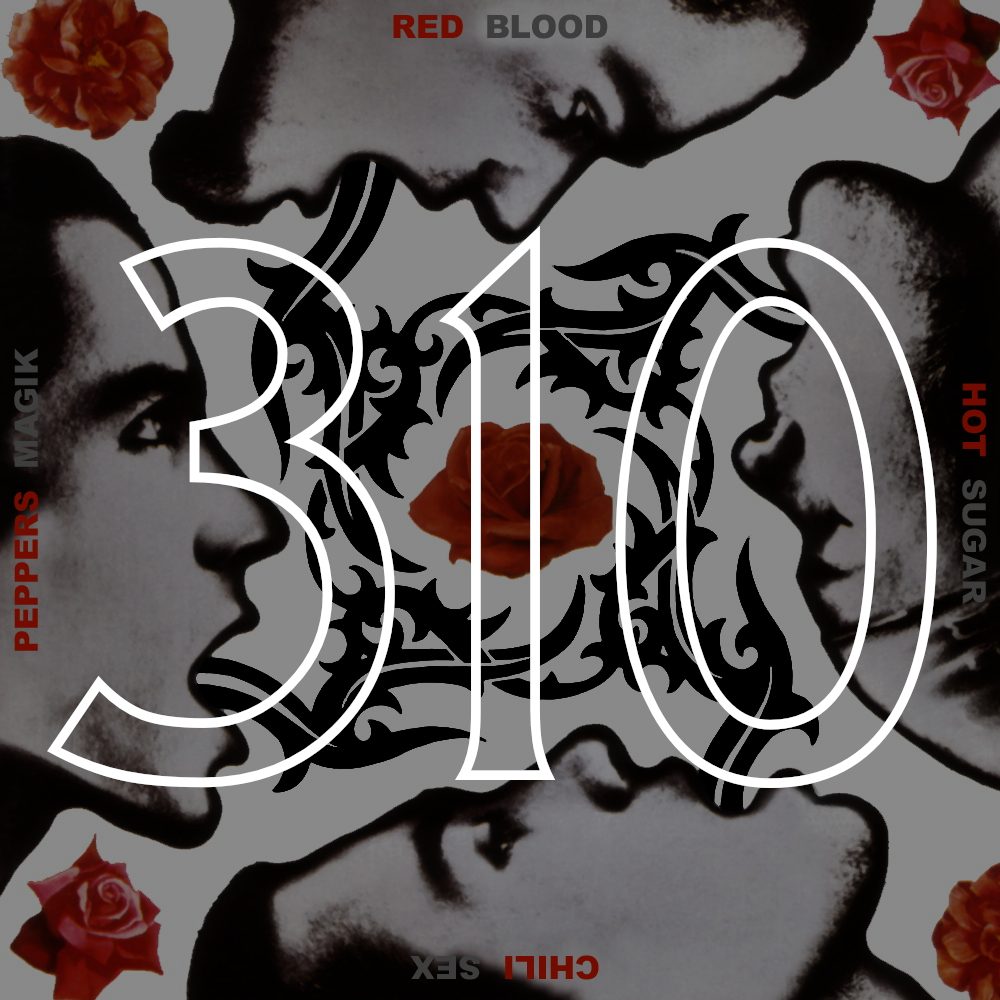

#310: Red Hot Chili Peppers, "Blood Sugar Sex Magik" (1991)

Nicole is waiting under the bridge for her friend Cass, kicking at the empty beer cans that have piled up with the rocks and leaves, when she sees the man with the notebook. He’s about ten yards below her, sitting on a rock near the sagging chain link fence just above where the ridge drops down into the river, and though it looks as though he’s writing, there’s nothing in his hand. She disbelieves this at first, squints and leans closer, almost losing her balance on the steep slope, but no, there’s definitely nothing there, though his hand moves across the page and his fingers are poised in grip around an invisible pencil. He looks up at her and she drops her gaze back to the beer cans.

She should be in school right now. It’s 11 a.m., and third period is just starting. She should be in English, sitting at her desk behind Jason Pierce, who is blonde and on the swim team and never turns around, but whenever he reaches one hand behind him to scratch at a mole on his neck, she stares at his fingers, the nails chewed down to the quick.

The man closes his notebook and stands. He waves to her and says something that she doesn’t hear. She half-lifts one hand in response. He seems to take that as an invitation, for he climbs up the ridge to her. He stumbles over a tree root, but doesn’t fall. He stops below her, making her taller than him. Close up, she can see that, though his hair is graying, though lines surround his eyes, he is younger than she’d thought, maybe only in his fifties or sixties. He’s wearing a parka, the same shade of forest green as the notebook, which he has tucked under his arm. He smells the way her friend Cass often smells these days, the way her mother smells, and so Nicole knows he has been drinking.

“I said, shouldn’t you be in school?” he says.

“I’m eighteen,” she says, which isn’t an answer.

“That’s nice,” he says, and from the half-smile he gives her, she knows he knows she’s lying. She’s sixteen.

She shifts her weight, taps one toe against a can. A few splashes of liquid slosh inside as it rolls away from her. She crosses her arms. She wishes she had a cigarette. She usually only smokes with Cass, and then just a puff or two, but she feels the need, now, for something to do, a reason to be standing under the bridge.

As if reading her mind, the man says, “Cigarette?”

She shrugs. “Okay.”

He taps two out of the pack and holds one out to her. When she takes it, the tips of her fingernails scrape against his palm. He doesn’t flinch. She puts it in her mouth and leans forward, careful not to fall, for him to light it for her, like she’s seen Cass do when she’s trying to impress the seniors that like to skate around the steps of the elementary school, practicing their ollies and kick flips and rail slides. The smoke catches in her throat as she breathes in and she lets it out in a small cough.

The man smiles. “I was new once, too,” he says, and Nicole feels herself flush.

“Whatever,” she says, which is what she thinks Cass would say. She wishes he would leave.

“I mean it,” he says. “Shit, I used to play hooky all the time.”

She takes another drag on the cigarette. It doesn’t burn as much this time. She’s remembering how this works.

“I’d hang out under bridges, just like you, smoking, drinking, getting fucked up,” he says. “That’s all my life was, for a while. I was in this band, and we weren’t even shit, we’d had albums drop, they’d done pretty well, people knew us, but I didn’t care about any of that.”

Nicole wishes now she hadn’t taken the cigarette. Her throat is already sore, and now she has to listen to the man. She should’ve climbed up the ridge and back onto the street as soon as he’d approached her. Not that there’d necessarily be anyone there—this neighborhood, the neighborhood that Nicole and Cass had loved to explore as children, was dead. Cass was always complaining about it—but at least she’d be more visible. If Cass had been on time—but Cass was Cass, and never on time once in her life, and Nicole should have known that when Cass said to skip school and meet her under the bridge at 11, what she really meant was that she’d show up when she felt like it, and Nicole would need to be waiting when she did.

“I got clean, though,” the man is saying. “Hardest goddamn thing I ever did in my life.” He stares at her like he’s trying to tell her something with his eyes. She looks at the cigarette between her fingers. It’s burning down, and ash drops onto her shoe. “I wrote a song about it,” the man says. “You probably know it.” He hums a few bars.

“Yeah,” she says. “Maybe.” She doesn’t recognize it at all.

Up above, she can see a person’s head round the corner, heading toward the bridge. Cass. Late, as always, but she always showed up. Nicole drops the cigarette and stamps it out with her shoe. “I’ve got to go,” she says. “My friend.”

“Sure,” the man says. “Well. It’s been nice talking to you.”

“Thanks for the smoke,” she says.

“Anytime,” he says. He pats the notebook under his arm. “I’m around.”

Now, on the verge of her departure, she feels guilty for leaving. “What are you writing?”

“Poetry,” he says. “Songs.”

“For your band?” she asks. She wants to ask how he writes them without a pen, but doesn’t.

He looks at the notebook, then back at her. His smile is more of a grimace. “For redemption,” he says. He drops his cigarette butt. It glows against the leaves and for a moment, she thinks they might light from its embers, but then it fades into nothing.

Nicole scrambles back up the ridge to the sidewalk. Cass is there, scraping the bottom of her shoe against the curb. “Fucking stepped in gum,” she says. Her voice is so annoyed, so sassy, so Cass, that Nicole crosses her arms to keep from hugging her. “Who were you talking to?” Cass asks.

“Just some old bum,” Nicole says. “He gave me a cigarette.”

Cass wrinkles her nose, though Nicole doesn’t know if it’s at the man or the state of her shoe, pink strings now dangling between the sole and the curb, like she’s a cartoon character stuck in place. “What a perv,” she says.

“He was actually pretty nice,” Nicole says, which she realizes now is true. “He said he used to be in a band. I guess they were famous.”

“Really?” Cass says, and Nicole can see her interest peak. “What band? How famous?”

Nicole shrugs. “He wasn’t, really,” she says. “He’s just lonely.”

“Whatever,” Cass says. “Let’s go then. Who gives a shit about some old man?” She hops back onto the sidewalk, her attempt at fixing her shoe abandoned, and takes Nicole’s arm. “You remember Drew Hanes? He graduated a couple years ago? He’s in town with his band, a real band, not some fucking imaginary one, and he invited us to watch them practice. Come on.”

But Nicole turns and looks back down the ridge before they walk away. She’s expecting the man to be watching her, for him to wave, but he isn’t looking at her at all. He’s sitting back on his rock, staring out at the river, at its current that carries all manner of objects south. And Nicole knows somehow that he is more interested in the leaves, branches, fish, beer cans, plastic bags, needles, bodies, all manner of detritus trapped in the river’s current than he is in her, and she knows, too, that he will stay there, under the bridge, watching the river and writing his poems and songs until his fingers are too cold to grip his pencil, and then he will close the notebook and climb up the ridge, and set off down the road, where there will be more bridges, more rivers, more poems, but no redemption, no saving grace for him to find.

Cass yanks gently at her arm. “Hey,” she says. “Coming?”

“Sorry,” Nicole says, and she turns away from the man, and, her arm still linked with Cass’s, she walks away from the bridge.

—Emma Riehle Bohmann