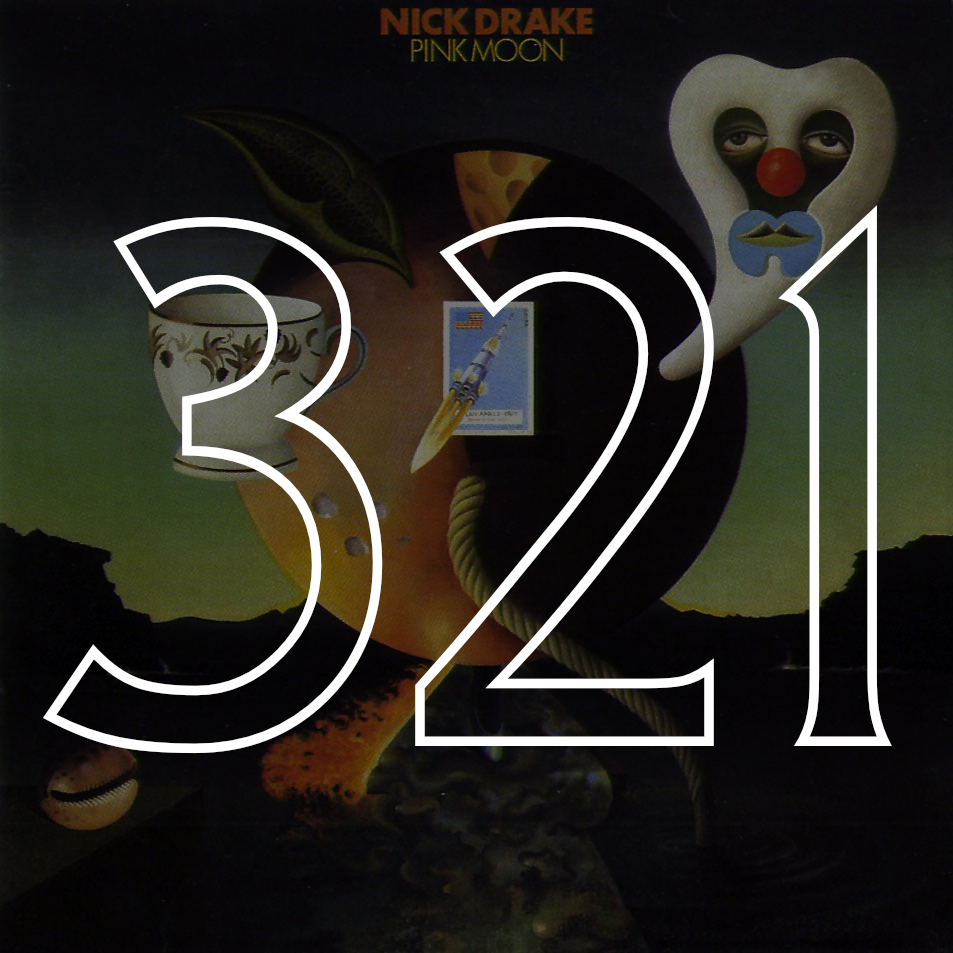

#321: Nick Drake, "Pink Moon" (1972)

Black bile // earth — autumn — gallbladder

What are we supposed to do with our melancholy? The very nature of the beast seems to disallow us any access whatsoever to its correction—but so it goes, I suppose, with sadness, with despondency, with lethargy and unspecific restlessness. In order to stop feeling melancholy, you need to ease up on the melancholy, and the only thing that prevents us from easing up is that same melancholy. This is why it feels like a stone, or a sledgehammer, or a coarse iron blanket. This is why it’s difficult for others who aren’t under that same stone or lifting that same sledgehammer to understand. This is why we must remember empathy—this is how our forgetfulness of this holes up in echoing hovels where it decides to rest forever, gnashing and gnashing and gnashing.

“Melancholy” comes from the Greek melas and khole—literally “black” and “bile.” It was Hippocrates who assigned the humor to the disposition, proclaiming depression as the unfortunate effect of an excess of black bile, the darkest clot at the bottom of a sample of blood exposed to open air. Characteristic temperaments include despondency, seriousness, and quiet. There are innumerable types of quiet, though. We know that. The quiet of thought. The quiet of study. The quiet of awe. The quiet of anger or mule-headedness or peace. The quiet of sadness, of course. The quiet of sadness. What are we supposed to do with our quiet sadness? How are we supposed to name it, sit with it, overcome it, share and revel in it all at once? How can we make joy from it, or at the very least normalcy? At the very most art.

Autumn belongs to melancholy—the humorists have wrought it, and it is so. It feels right—the quickening early nights, the sighful memories of summer. Nick Drake recorded the entirety of Pink Moon, the greatest contribution to humankind’s infinite annals of great melancholic art, in the middle of autumn. Three years later, he died nearer to the end of the season, a mysterious death eventually claimed as suicide by antidepressant overdose. He had swallowed thirty at once. I don’t mean to make a joke when I say I imagine his bile most likely had never been blacker. The discoloration of such medicine in such excess, the melancholy to match—one begins to consider Hippocrates more closely.

Phlegm // water — winter — brain & lungs

What are we supposed to do with our apathy? Its very nature disallows us access to its correction. Disinterest consumes the basest level of what we’re doing here in the first place. Here, that is, on Earth, in life, walking and dreaming and loving or looking to be loved day in and day out. When we lose interest or have difficulty getting going, we translate our movements like ghosts, appearing some place then disappearing without much of a second thought. “I don’t care,” I say all the time. Too often. And I don’t. I mean it. What am I supposed to do? Care?

Humorists attribute phlegm to the brain and lungs, where it was originally believed to have been made and stored. Extreme apathy was understood as the result of an excess of phlegm in the body—measures needed to be taken to release it and restore the balance. Emetics might be administered to force vomiting, typically salt water or mustard water, potentially both, potentially at the same time. In my first year of college, I awoke one morning at the end of February nearly unable to breathe, gasping like a comical fish on land, rubbing a new pain in the center of my chest. Testing revealed that my left lung had collapsed, seized more or less inward on itself thanks to a hole the size of a dime which opened up overnight. The air my lung stored with intent to keep me alive drained slowly, then quickly—it was ninety percent gone by the time I made it in for surgery. No warning, no reason, no logical larger affliction—hence the “spontaneous” in spontaneous pneumothorax.

I’m considering Hippocrates more closely now. When my lung collapsed I was closer to death than I’d been before and have been since, but I wouldn’t say I was necessarily “near death.” When I recovered I wasn’t given a new lease on life or any other such appropriate platitude. But for a little while I did receive attention, much more so than any average someone receives in any average week or two. Educators gave me innumerable extensions coupled with sincere well wishes. Priests from two different denominations visited my hospital bedside. My mother took too much time off work to sleep in a chair and buy me candy from the machine downstairs. Three friends wrote me a get-well song and sang it from the foot of my eternally wincing, prostrate position.

Here is why I mention this: the morphine drip made me vomit over and over again, but there is no better cure for apathy than the feeling that you’ve suddenly and rightfully become the center of the universe. Like all major transitions, freshman year of college is difficult in a hundred different ways. It is difficult to care about anything, and that has at least a little do with the sudden feeling that now, away from home, in larger classrooms, at the bottom of the food chain once again, you mean very little. I don’t know if there is phlegm in my lungs. I do know that the cure for my disinterest came when that humor’s home burst open.

There is no apathy in the short breadth of Nick Drake’s musical career. Three albums in three years: a confidence and vigor in the first, focus and diligent sheen in the second, and a third utterly stripped of ambition, beset only by some unshakeable drive to keep at it despite the odds. You would not think “drive” when you listen to Pink Moon, so downtrodden are the songs within, so tired does Nick sound. It was recorded in two days with one microphone and one guitar and as few takes as possible without sounding like crap. But this is Nick, full of phlegm, fighting through it. Changing things up to try for recognition from a different angle altogether. The record is not a goodbye letter—it is a sign, for sure, but of what is the better question. Of one man’s dogged plea to be heard, to be seen, is the best answer I have.

Blood // air — spring — liver

Joe Boyd, notorious upstart American producer and Nick Drake’s mentor and friend, describes receiving Nick’s first bedroom demo in 1968: “I called him up….and we talked, and I just said, I’d like to make a record. He stammered, Oh, well, yeah. Okay. Nick was a man of few words.”

There is a video on the internet that has raised a lot of speculation. A very tall man wearing bellbottoms and a dark maroon jacket lopes away from the camera in semi-slow motion. He is in a thin crowd at what appears to be an outdoor festival. The description: Live footage of Nick Drake in the crowd at an unknown 70's folk festival. Got sent this vid by a mate. He reckons the suit jacket, short sleeves long arms and general appearance are a givaway [sic]. What do you think. The comments section is full of debate. The similarities to the Patterson-Gimlin Bigfoot footage are eerie. It is the only footage I’ve ever seen of what could even potentially be even a fake Nick Drake in motion.

Nick’s sister Gabrielle, one of his closest confidants, describes the moment she discovered that he’d finished his first record: “He was very secretive. I knew he was making an album but I didn't know what stage of completion it was at until he walked into my room and said, There you are. He threw it onto the bed and walked out.”

After recording Pink Moon, an album his label hadn’t asked for and wasn’t expecting, Nick dropped the master tapes off himself at his boss’ offices. The story goes that he handed them to the receptionist without a word and walked back out. Not angry or sullen, just….inward. Inside himself. Others discount the story, say he handed the music personally to the head of the label, but the point’s the same all the same. Pink Moon was a record for no one from a no one who had one last go in him.

On its release, Nick gave only one interview, for which he needed excessive coercion. The interviewer, Jerry Gilbert of Sounds Magazine: “There wasn’t any connection whatsoever. I don’t think he made eye contact with me once.”

Blood is meant to make us sanguine: lively, carefree, social, talkative, bubbly, out and about, personable, energized. Nick Drake must have been the most bloodless person the record industry had ever seen.

Yellow bile // fire — summer — spleen

One wonders what Nick Drake’s career might have looked like if it looked more like Kurt Cobain’s. I understand the comparison is imperfect, but listen. Both were on the hunt for fame under others’ assumptions, either posthumously or in their lifetime, that neither wanted fame. The unwilling voice of a generation, we think of it, or at least the sullen next big thing who accepts his fate with hands tied. The story is better this way—but it’s inaccurate, which saddens it. Nick Drake wanted to be heard. He wanted his records to sell. He believed he was a great songwriter and he wanted the rest of the world to know it. And Kurt wanted to be a rockstar. From day one, his idols were the Beatles, the Who, and Zeppelin. The big guns. He wanted to tour every country on earth and see his face on magazines and live in comfort.

Obviously, the former took his own life a disappointed nobody—in his own eyes—and the latter a disappointed anointed god. Kurt got what he wanted and much more than he’d bargained for; Nick tried and tried and tried one last time, and nothing. Third time was certainly not a charm—if anything, in hindsight, and maybe even more so at the time, Pink Moon seems like an unshackled fuck-it than any sort of last ditch grasp at success. But the record is perfect. It is a perfect record.

I think Nick Drake knew it. These songs are not tossed off. They’re meticulous. Some had been written years before, some were newer, but all show the clear signs of having been practiced, played, a thousand times before. The record feels lived in, coddled over, extremely precise. Nick Drake comes across like a watchmaker all throughout—there’s a reason Pink Moon covers are hard to find, and the ones that do exist are lifeless. They are not easy songs, but the way Nick plays and sings is all confidence. Choleric. Energized. Even aggressive.

Yellow bile is meant to bring this out, this lively temperament. And they are not words or ideals that you would initially associate with Nick, or with Pink Moon, I know. But they speak volumes beneath the surface. Talent can be that way. It can grab you by the hand, or the throat. Nick Drake dropped out of university halfway through to make music and see where the road could take him. He wasn’t failing academically, but he recognized his talent and pursued. He expected esteem for his work, as the choleric often do. Pink Moon is what he left to show he’d given up the chase. And no surrender has ever been so perfect.

—Brad Efford