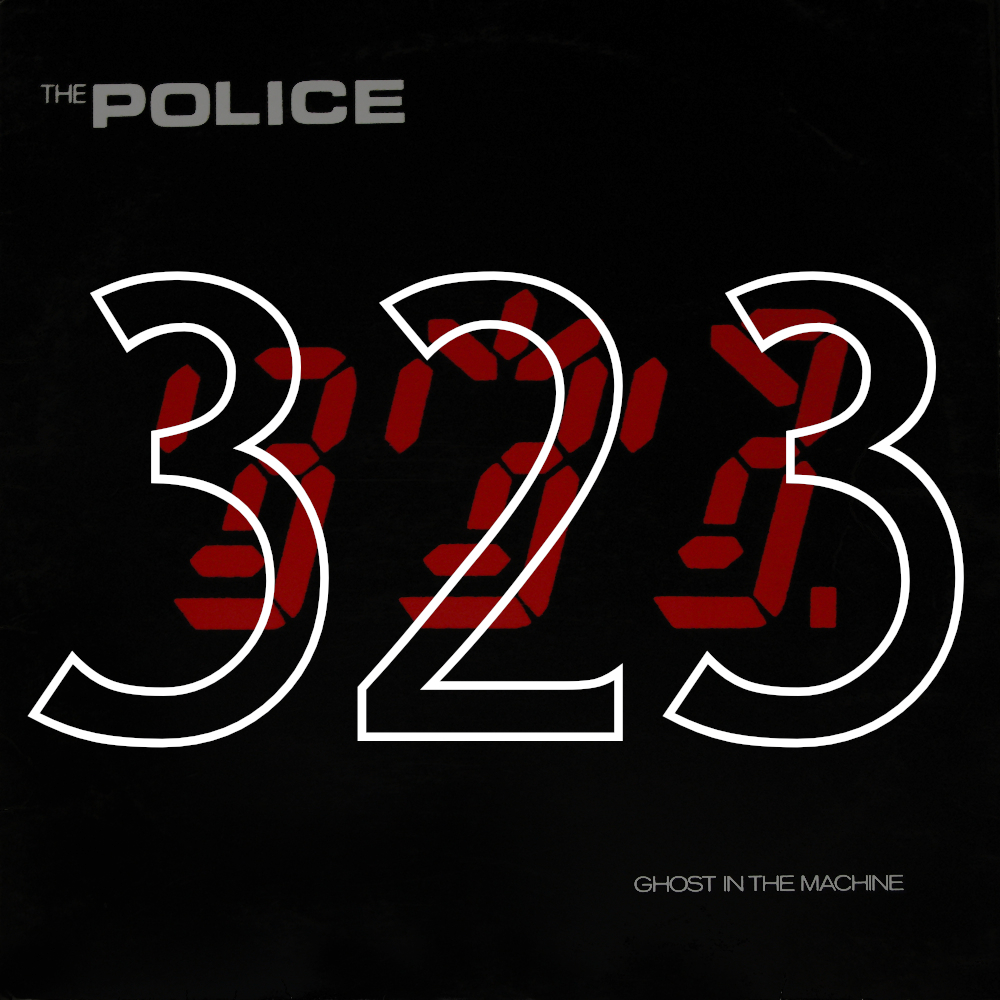

#323: The Police, "Ghost in the Machine" (1981)

Two weeks after my brother came home from Iraq in a coffin, I received a letter from him in which he said that if anything were to happen to him, his magic books were hidden in an old Converse shoe box on the top shelf of his closet. My brother—ten years older than me and therefore my idol who I worshipped with an intensity I wouldn’t see again until I discovered whiskey at the relatively advanced age of 22, being a late bloomer in drinking as I was in everything else—was a magician. Not the pulling rabbits out of a hat, sawing coffins in half, escaping handcuffs, death-defying type of magician, in a top hat and suit, standing on a stage in front of an audience of hundreds. My brother specialized in sleight of hand, card tricks, hypnosis, and, his favorite, mind reading. He carried a set of index cards and a permanent marker in his pocket at all times, where he would write down his prediction of what I was going to say. I’d put the folded-up card in my pocket and let him lead me through conversations, always confident that I could outsmart him, only to find, at the end, when I unfolded the card, the items I’d chosen scribbled there.

He’d written the letter the day before the IED hit his tank, killing him and one other. The letter came to me with a note from someone, another soldier presumably, who said he’d found it while packing up my brother’s belongings. He said the letter hadn’t even been put in an envelope yet, and so he’d read it, and thought that since it seemed private, it should come directly to me, rather than in the box of my brother’s belongings that arrived at our house with his body. The note was signed with initials, T.J. Years later—after the discovery of whiskey, at least a third of a bottle in—I’d wonder if the letter had been sealed but T.J. had opened it. I’d wonder if T.J. had been in love with my brother and needed to know what his nearly-last words had been. And then I’d cry for poor T.J., the love of his life killed in an explosion, shipped back in a closed coffin to a family T.J. would never meet, like maybe sending that note to me, the little sister, was his attempt to form a connection with us, and I, being only thirteen, had ignored it.

After I read the letter, I went into my brother’s room. My mother had closed the door the day he’d shipped out and forbidden anyone to enter, like she had somehow known what was to happen, just as my brother had known what numbers I’d choose, and was turning it into a shrine early, though I’d often heard, through the wall that our bedrooms shared, the squeaking of his box spring as she sat on it, followed shortly by the muffled sniffs that marked my mother’s tears. But I knew she wouldn’t come in while I searched for the book, as my aunt had dragged her—against her will—to a grief group after dinner. My father was downstairs, lost in a glass of whiskey. It was just me and the letter and T.J.’s note and my brother’s room, where I dragged his desk chair to the closet so I could reach the top shelf.

In his letter, he’d said the books were hidden, but I found the shoe box easily, stuffed behind an old duffel bag filled with the plastic dinosaurs he’d loved as a child. I pulled the shoebox down and sat on the desk chair, still facing into the closet so my brother’s letter jacket from high school—football and track, both received his senior year so he’d had just one winter to wear it—was inches from my face. It still smelled of leather, and the sleeve hanging in my vision was barely creased. I looked at that sleeve, at the patches for his sports, and I let my hands rest on top of the cardboard box. I was surprised at how light it was; I’d thought his magic books would weigh more. I’d pictured large tomes, ancient volumes of secrets. Even at thirteen, I knew I’d been romanticizing it, but he’d been the typical older brother, never letting me in his room, and so I’d built it into some kind of secret lair in my mind.

I remember, now, that what struck me most, at the time of my brother’s death, was the way everyone kept lamenting how young he was. And he was—his twenty-third birthday had been just two months prior to his run-in with the IED. But for some reason, at thirteen, these sentiments angered me. “So young,” his 11th grade English teacher said at the funeral. “Only 23!” said my aunt through her tears. “He was in his prime,” my father’s best friend said. “It should have been me,” said my grandfather. Every time someone mentioned or alluded to my brother’s age, I wanted to scream. Like younger children didn’t die all the time. Like he was the only 23-year-old to ever be killed. Like we weren’t all at danger, every day, of being hit by a car, falling out of a tree, struck by lightning, the odds of which, to me, anyway, seemed greater than a truck hitting an IED in some desert country halfway across the world that I couldn’t even picture. I think now that what angered me weren’t the lamentations of his age, but the platitudes they came in. They were impersonal, and made my brother feel like he was made of the same cardboard as the Converse shoebox in my hands. I know now that when the worst thing happens, people resort to pithy sayings and clichés because they’re in shock, because they understand that there are no words to describe their anguish, but that saying something feels better than keeping silent, but I was too young then to understand any of this.

What I remember, very clearly, is my decision not to open the shoebox. I suddenly couldn’t stand the idea of my brother’s secrets being revealed to me. For his tricks that so astounded me, even at thirteen, when I felt so wise about so much, to turn out to be mere hoaxes that I could learn myself felt like my brother would die all over again. I pushed the chair out of the closet and, hugging the shoebox to my chest, ran out of his room, down the stairs, past my father in the living room, who looked up at me from his glass but said nothing, through the kitchen, my socks slipping against the linoleum floor, out the back door, dashing across the sidewalk until I reached the big black dumpster in the alley next to the garage. I threw open its lid and set the shoebox at my feet. Then I picked up each book, one by one, and ripped out the pages. I didn’t even look at the titles. There were four books total, paperbacks no thicker than the Patrick O’Brian sea adventures my father loved so much, and I destroyed each of them, threw their words into the cavernous mouth of the dumpster until they were in shreds, all four of them, and then I dropped in the shoebox and closed the lid and sat down on the concrete driveway and cried.

And I thought then not of my brother as he must have been in his last moments before the tank exploded in a burst of heat, not of the way he lifted me off the ground when he hugged me goodbye, not of the fact that his favorite flavor of ice cream was cookies and cream, and he liked Pepsi better than Coke, and he plucked the stray hairs between his eyebrows, not of T.J. and the love he may or may not have borne my brother, love which may or may not have been reciprocated, but of the first magic trick I could remember. I was three, maybe four, in a booster seat in the car on a long ride to somewhere, my brother sitting next to me, our parents in the front, and my brother turned to me and said, “Look, I’ve lost my thumb.” He’d just folded it down, hidden it between his other fingers, but I didn’t know that. I screamed in terror—he’d lost his thumb!—and my mother snapped at my brother and my father laughed, and my brother held up both hands in front of me and said, “Look, it’s just a trick. See, just a trick.” I grabbed onto his two thumbs with my two hands, and they were so big, bigger than my hands, and both real, both there, and I stopped crying, because he was right. It was just a trick, and he was fine.

—Emma Riehle Bohmann