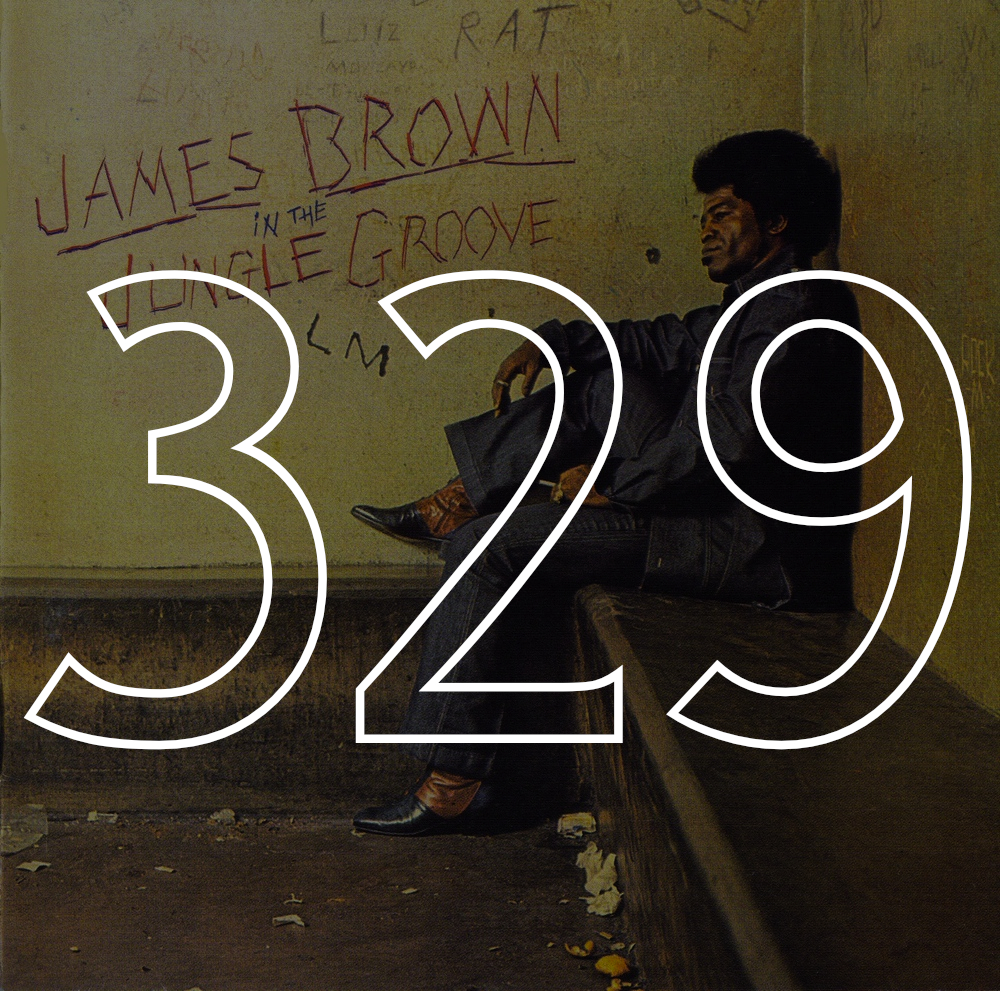

#329: James Brown, "In the Jungle Groove" (1986)

FELLAS THINGS DONE GOT TOO FAR GONE

Clyde could barely feel the weight of the sticks in his hands; they hung at the ready as he shifted his body. The stool behind the kit was tilted. The walls hung with carpeting kept the sound penned in. There were no windows.

But James’s voice hung like a chandelier in that cramped room. Others chimed in over the intercom as the tape reels began to spin and Jimmy broke out with a bold stroke. The air jabbered. Horns flanked from either side and with a quick eye from the man Clyde laid it down. James took to the rug and got to work.

Soon the room was taken in by the groove—the kicks, snares, claps, and cymbals rode the ebb and kept the pace. It was give and take. Each player sharing the ring, bobbing and weaving, sparring like the prelude to a fistfight, or rather giving each other space to walk it out.

Throughout the session there was no fanfare beyond their noise. Streamers didn’t fall, and by round of applause they were not crowned the winners. But pressed in the grooves, housed in the vinyl, the moment gestured to a time beyond the known horizon; waiting in the crates like a quiet storm.

CAN I SAY SOMETHING?

In The Jungle Groove was not a record in the proper sense. Its intention was to capitalize on a sound that was beginning to gain traction among a burgeoning generation of music consumers. A compilation of tracks remixed and unreleased that captured the shards of funk and soul that went on to be the seeds of hip-hop; if anything, this record was a greatest hits for what would be the foundation of a genre.

Released in August 1986, the album boasted cuts recorded almost two decades prior that had gathered dust, or lacked the grace of a proper pressing. Aimed at “true students of the Godfather” and eschewed for passive listening, what it was was a weapon. In nine tracks and clocking in at just over an hour, what followed was a veritable arsenal of samples: horns, yells, cuts, grooves, loops, and breaks that when pulled tight caught voices in a soft landing.

For MCs that needed training, it was an arena—to run tires and jump rope, to make sense of a world that demanded stillness in the wake of oppression. For producers, it became the hallmark of a sound.

CAN I GET A WITNESS?

It’s windy and raining. The traffic off the lake hums at midday, the din of engines idles. Inside the record shop, behind walls of glass blocks, the light spills across the crates in dishwater grey. Thumbing through, your hands pause over the image of a man at rest, leg up, in a train station, at a bus stop, in a holding cell. Dressed in all denim with an unlit cigarette. In The Jungle Groove scrawled in graffiti script. You’ve heard of James Brown, sure, who hasn’t, but never this. Stuck to the plastic cover above his profile someone’s written in marker:

“Quintessential” “An underground number one” “—a classic”

And before you know it you’re making your way across the store to the listening station.

“Be careful with that one, and no scratching,” the owner punctuates with a nod toward the vinyl in your hand. Scratching? You carefully remove the record and place it on the table. Adjusting the headphones, you drop the needle on side one and wait in cushioned silence. Then that voice: “Fellas, things done got too far gone…” and you’re hit full on with horns, drums, guitar and your mouth slides open without you noticing.

The minutes fall away. You have a sudden urge to feel the record, a tactile desire. To pull back the drums, to walk back the voice, that voice. You look around. You can feel the grooves in your prints circling below; that drag. Shoulder pressed to ear and you lay your tips down on the track like a hand to a lover’s back. And suddenly you bring it back with the angle of rotation on the table like ERREEEHHKK and then the guy from behind the counter pulls you back.

CAN I TELL ‘UM?

When sunsets burned low to the smell of charcoal the heat was the last thing to break: the cooler and bottles sweating, the hydrant cracked open. The layered voices and fading sun caught in blocks by the smoke. Clotheslines hung over the block like banners and flags as children and neighbors hopscotched, slapped thighs, and told stories. From inside the needle on the song spilled a groove into the street; the ricocheted shuffle off the record, the arm jumping with soles on the parquet as plastic forks scraped paper plates.

At the end of the block DIY contraptions and repurposed amplifiers rose from milk crates and garbage cans. RCA turntables pulled from home stereos came together on a broken door set on cinderblocks with power cables running to the streetlights. With everything connected all eyes turned toward the sun and its descent. Falling from full orange roundness to half, to a sliver of light above the buildings, and like a synapse the city grid rushed to fill the encroaching darkness. When the bulb above threw its glow the equipment began to hum, the energy kinetic. Hands up and down the block went up with a cry as the needle hit the groove and sound rushed to the corners of the evening.

PUT YOUR HAND ON THE BOX AND FEEL THIS

The boombox entered the park at shoulder height, held fast by a heavy ringed hand with volume on full blast. It was just after sundown, and the gazebo at the center, old fashioned and weather-worn, hung in a halo of sodium light. Unremarkable were it not for the brothers dragging cardboard, pounding it flat on the wooden floor, milling about, stretching. And with the mounting of steps, the sound amplified naturally under the vaulted ceiling, and the bodies closed in around it. A mesh of chatter and trash talking hung just below the drums.

“Who we got on deck?”

“My man stole fire, you cut this tape?”

“My ol’ man worked late so I copped his stereo.”

“Shit’s hot!”

“Man how you get it to ride on like that?”

“Some cats, they tape up their breaks. I catch mine right every time.”

“Shit man, get outta here.”

“Ha almost copped yourself a foot!”

“When you see a man doing a windmill you stand down.”

Each tight coil of limbs unfurled into the physical embodiment of sound. The legs swung with the sticks, hands working overtime. When the tape faded into hiss the ringed hand would flip sides and it all picked right back up. Entering one by one they took turns, paid homage to the music, and kept it cool as ice.

KEEP ON SINGIN KEEP ON SINGIN KEEP ON SINGIN

KEEP ON SINGIN KEEP ON SINGIN KEEP ON SINGIN

KEEP ON SINGIN KEEP ON SINGIN KEEP ON SINGIN

Never in your life had you been told to fear the pavement. You learned to walk on those sun-hot slabs that scraped away the skin from your knees. Now you’ve had to offer way more than skin. The murmurs that you’d heard, that hate had taken over. It was never real beyond what hung like sour apples in your feed. You think for just a flash about the first place you tasted caramel, the sound of sirens blurred with horns, the word petrichor and how it used to rain.

Ultimately your mind hurtles back to a time when your family went out walking on a Sunday. Hand in hand by the lake and your momma held your hand with her hair tied up like when you said you think of her wearing nothing but that scarf and a smile. How that skin meant the world to you, a hunger for the taste of salt. Pretty soon it’s just dark but the feeling stays to linger.

You worry now just like you used to, but now the film whispers too in place of just you. We move as a team, we never move alone.

So when I say hut motherfucker you run like your momma calling. There’s no room for spare luggage. There’s no ‘I'll meet you there,’ it's a we all go or we ain't moving. I got nothing but love for you baby can you dig it?

—Nick Graveline