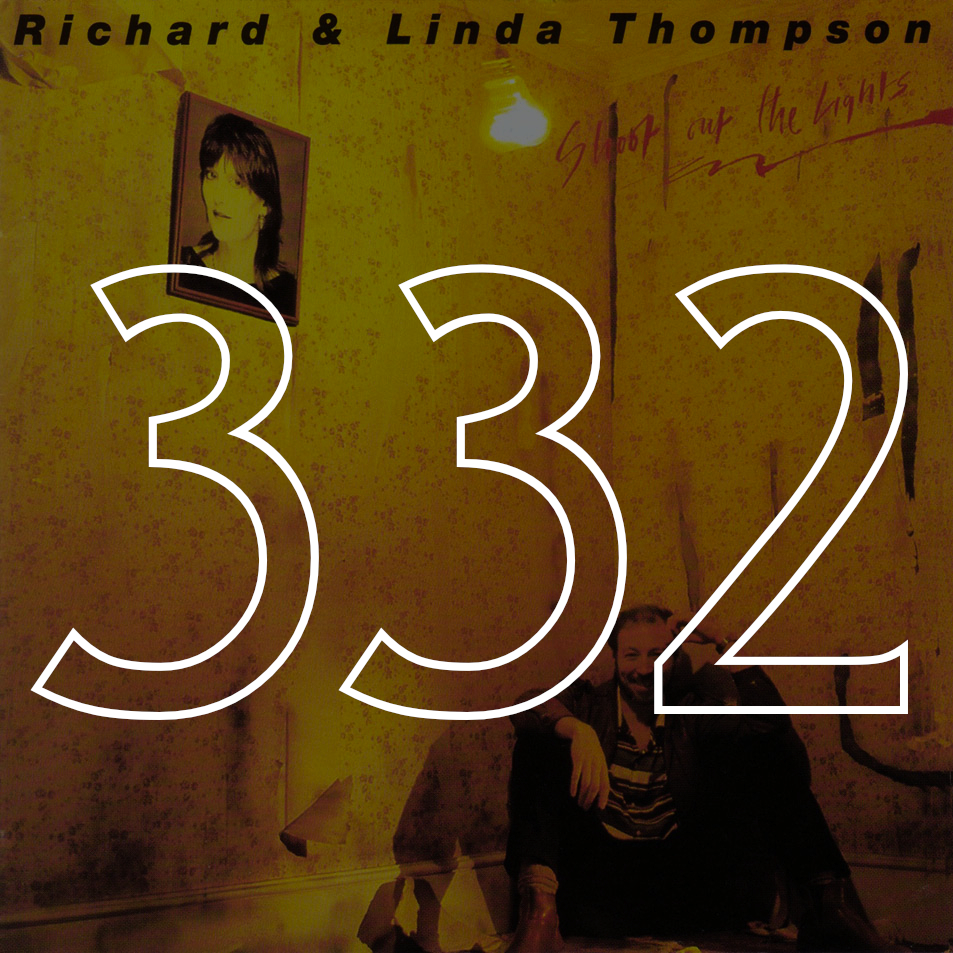

#332: Richard & Linda Thompson, "Shoot Out the Lights" (1982)

“Remember /

when we were hand in hand?”

But no, no—I don’t want to go there.

This is not a breakup album.

So many of the pieces on this site about rock and roll are about lost love, cruel break-ups, drift-outs, sappy, hapless exits. So many of the first lines are laced with bittersweet nostalgia:

“My mother listened to Springsteen’s ‘One Step Up’ when she left my father.” (#467)

“We were on a mountain in Switzerland when Beth told me she didn’t think she loved me anymore.” (#383)

“That I loved him there is no question, I can say that now that he is gone.” (#425)

“The last time I saw Tiff…” (#471)

“Where the fuck was she, anyway?” (#460)

“We were about one year in, and I’d already learned not to open myself up to your judgment. But I wanted someone

to help me choose new glasses.” (#355)

“At some point in college I acquired a Smiths album.” (#473)

“In graduate school, a common seminar move was to say, “I think we need to talk not about [singular noun] but about

[plural noun]”—not sexuality, but sexualities.” (#400)

“But then her cat died.” (#354)

“Most of all, he remembers her scent.” (#384)

“Is it fair to love an album for its last song?” (#395)

I had an anti-romantic image in my mind of what my first contribution to this project—this website about rock and roll!—would be. It would be baroque and unrelatable. It would not be about youth. It would not be about loss or college. It would be inedible.

A wild futuristic fuck you!

An anti-punk arabesque snake temple for old people!

If there needed to be cybernetics, there would be cybernetics!

And then my turn came, and Shoot Out The Lights was up for grabs, and I salivated and snatched it up. —I love this album! —It’s about taking aim. And darkness. —And Richard Thompson is on the cover looking smug. —And there’s only one light bulb left in the spaceship! —And he’s shooting it out!

And having chosen this flickering force field on which to map my progressive essay not about love and not about loss and not about heartsickness or my 20s or 30s—

I caught the cool eyes of Linda Thompson, looking down at me warily from her portrait on the peeling wall, and I remembered what this album is. Or, what it’s supposed to be: One of the great albums about the end of a marriage. One of the great albums about love in its death throes.

Maybe, definitely, like, the 3rd greatest late-70s/early-80s rock and roll breakup album.

And what could be sadder and lovelier and more bitter than Richard Thompson writing lines like “Don’t use me endlessly / It’s too long / too long to myself” and getting his soon-to-be-ex-wife Linda to sing them?

And what could be better nostalgia-fodder than an undeniably great love letter lost in the iPod shuffle (despite its greatness) behind those cooler, flashier “see ya” albums Blood on the Tracks and Rumours?

And so I’m tempted to write a narrative of love and loss and young romance that would pit this album against Dylan’s bleeding heart, and give Stevie and Lindsey a run for their witchy money. To write a romantic gut-punch that gives Richard and Linda’s story the 20th century gravity it deserves…

But I’m not going to do that.

Because this is not a breakup album, okay?

This is an album with the lines “The motion won't leave you / won't let you remain, don't worry / It's a restless wind / and a sleepless rain, don't worry.”

And it’s an album with the lines “In the dark who can see his face? / In the dark who can reach him?”

And even the most beautiful, heartbreaking song on the record—a song that’s obviously about Richard and Linda’s fraying love affair—

“I’m walking on a wire /

I’m walking on a wire…”

—calls to my mind a narrative not from my past, but from the other side of the world’s precarious sci-fi present:

In the last shot of Jia Zhangke’s film Still Life, we see Sanming, one of the two main characters, turn to face the jagged silhouette of the buildings he has been helping knock down.

Sanming is a coal miner from northern China, who has come far south to the Yangzi River to find his errant wife and daughter. While he searches for them, he finds work on a demolition crew. He spends his days tearing down the houses of Fengjie, an ancient city which, in a few months, will be completely submerged by the waters of the Yangzi as they rise behind the Three Gorges Dam (the enormous weight of which, it’s been calculated, will shift the earth’s poles and slow its rotation).

On his way home, Sanming looks back at his day’s work and sees a tightrope walker, calmly stepping through the air on a line strung between two half-destroyed buildings.

There is no explanation for any of this: the artist’s exercise, his risk and his flourish, as he balances between the two buildings doubly doomed by hammer and water. Sanming’s speechless watching. Our watching them both work their endlessness into the scar-scape. The film is over.

When Richard and Linda sing “I’m falling” together for the last time, they sound triumphant. It makes no sense.

And in the last moment of “Walking on a Wire,” when all he has to do to end the song is pluck his guitar one last time and bring the pain to a close, Richard Thompson hesitates.

The previous note is fading; the moment to act seems lost.

And when he finally ends it, too late, he knows damn well that with that pause and with that moment’s sweet tension, he’s embedded in our muscles the longing to hear it all again.

“Do it all day, the backstreet slide…”

Why do we want to write about our past when we write about music?

Is it an essayistic privileging of the music’s placement (its lyrical aspect, what it means to us, what it means to the culture) over its displacement (its geometrical aspect, its bullet in the brain, the lights it shoots out)?

This need to distance ourselves from a piece of music by “putting it in its place,” and comparing it to other, better (or worse) musical experiences—it’s the conceit that’s given order to this whole project. But does it come from the same hierarchical function of the brain which, as we get older, loses its nuance, keeps elevating one arbitrary set of memories over the rest, and eventually rigidifies into nostalgia?

“Oh, you've got to ride in one direction /

Until you find the right connection…”

Maybe the only way to do justice to loss is to never lose.

I think I could listen to “Walking on a Wire” for three hours on repeat and feel a thrill from it each time.

But if I distance myself from the music (and in the end, I have to distance myself) it should be by substituting space for space, sensory field for sensory field.

Writing can do this, if it’s got rhythm. If its presence hurts more than the absence it describes.

“Let me ride on the Wall of Death /

one more time.”

I listen to a rock song and I want to write. What’s happening to me?

It’s like reaching into clear river water to wash your hands and wanting to tattoo them. Like living and wanting to live.

So is it fair to love an album because its last song is called “Wall of Death?”

But no, no—because “Wall of Death” isn’t even a part of the album it nominally brings to a close. It transcends everything before it. There are those steely grinning, rising and falling, opening chords—and this is not a breakup album, and it never was.

This album is a carnival spaceship with a thousand light years to go! And only one light bulb left blurring—

—and in the star-scape of warp speed, Richard asks his estranged wife Linda to

sing with him a heroic ode to daring, to fear, to the wish to be as far away as anyone can imagine from security and domesticity.

It will be the last song on the last album they will make together.

But despite the love I have now, despite knowing I’ll remember it as love, I still want to write my anti-memory essay, my empirical orality play, my skin-tight depth-charge...

You can waste your time on the other rides, but I want the future, with its knife-edge and its garden hose running miracle blue! Its tangelos! Its speech bubbles shattering against the surface!

You’re going nowhere when you ride on a carousel, but baby, this website is a wall of death.

And through the steel cage I catch glints of where we’re headed:

#305: “The ghost of Lucinda Williams walks through Lake Charles. She’s blindfolded, holding a plastic bag with two goldfish in it. One’s the past. One’s the present. ‘Big Swirlie,’ she calls out to whoever will listen, ‘and Little Swirlie.’”

#235: “Her cabinet stands around her, their hands nervously twitching…but President Patsy Cline’s finger hesitates over that big red button. ‘Why should our destruction be mutual?’ she muses. ‘Why shouldn’t you have to survive, to watch me burn?’”

#206: “That little red corvette stays double-parked forever, collecting blue traffic tickets…”

#157: “The ‘again’ in the chorus of “Love Will Tear Us Apart’ suggests that love might also keep those two together.” – Graham Foust

#26: “In the future, time travel is possible. Your mission: go back to 1982, somehow get to Stevie Nicks. Tell her not to do anything else with this song, to just leave it like this forever: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RPEhIoKeTg0”

#16: “Bob Dylan’s in limbo, recovering from a carriage accident, his leg up in a yellowing cast. The cast, his living will and testament, has been signed by IBM’s robot overlord board of directors. ‘He’s left all his legacy to us,’ the e-board e-sings. Their hard drives have been uploaded directly from Dylan’s brain. But from a floral shadow in the corner of the hospital room, Woody Guthrie chuckles. ‘Take another look, knuckleheads,’ he says. ‘You’ve signed that cast in invisible ink.’”

#1: “Richard asks Linda to sing ‘Just the Motion’ with him one more time, ‘for the memories.’

‘What memories?’ they laugh.

They look back at Earth and sigh. How much of it, really, was about the music?

‘It’s clear that the Beatles are the only thing holding up the planet these days.

But…what’s underneath the Beatles?’

Richard grins. It’s an old joke of theirs.

Linda gives him that look. ‘Man, it’s Beatles all the way down.’”

—Joe Lennon