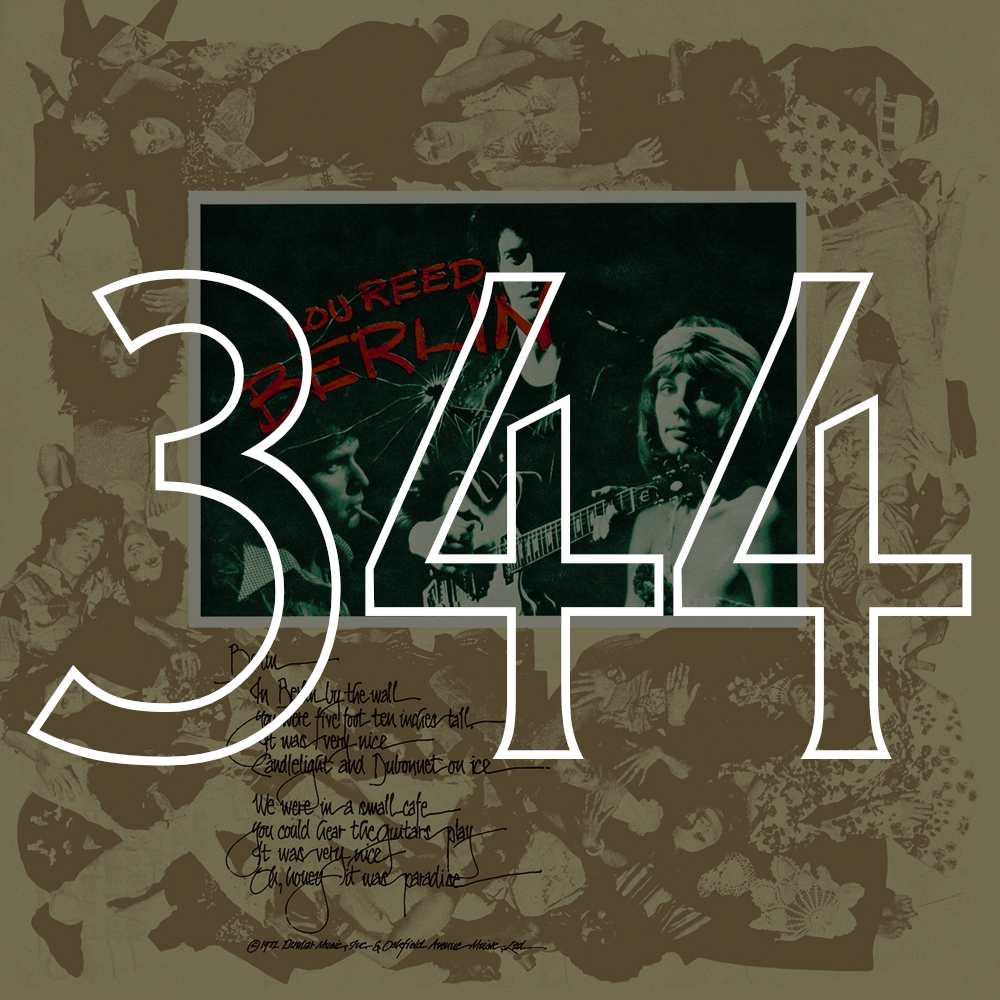

#344: Lou Reed, "Berlin" (1973)

I

Caroline says, “I love you. You know that, don’t you?” She cracks the passenger-side window and flicks out her cigarette. “I do love you, but sometimes love just isn’t enough.”

“I know you love me,” I say. “And I love you, but you’re right, it isn’t enough.”

Caroline and I are at the end of seven years—college sweethearts who later became residents of Oklahoma as I started my graduate career. But now, as we occupy the latter halves of our twenties, and after all those years together, the unit we once were has slowly bifurcated. I want to get married, and she doesn’t; I want kids, she prefers a life without; I’ll be starting my PhD in the fall, committing five more years of my life in this great state, while she has a career and a new job opportunity waiting for her in the District come December. With these last few weeks, Caroline and I are going to make the best of it, enjoy our time together, and when December arrives, I’ll drive her back east and we’ll become intimate strangers because love isn’t enough.

“Here,” she says. “This is the exit.”

We pull into Frontier City, a western-themed amusement park outside of Oklahoma City, just as the gates open. It’s a few days before Halloween and the kids are dressed in costumes. Princesses, superheroes, pirates and ninjas, some ghosts. The park itself is adorned in cheap K-Mart decorations and some of the attraction names have been changed—scribbled over in fake blood—to puns. On the Brain Drain grounds is a makeshift cemetery. An assortment of latex arms and heads burst up through the ground. The mechanical cowboy musicians that entertain and bewilder children and seniors are decorated with cobwebs and rubber guts and organs, with foam skulls and bones resting at their feet. They are now billed as the Rolling Bones.

Caroline and myself spend a few minutes looking at the park map and decide to ride Silver Bullet. The attendant for the rollercoaster is dressed in a werewolf costume, the irony lost on no one. In line I listen to the teenagers in front of us discuss their rollercoaster photo game plan. Billy Bob is going to do this when the rollercoaster passes by the coaster cam, and Mary Sue will do that. I remember doing the same thing when I was their age, coordinating outrageous and humorous poses with my friends as the rollercoaster passed the camera. But we never accomplished our goals. No matter how many times we discussed the plan, we were never ready. When the rollercoaster shot off or took its first plunge, we all reacted with terror, some with delight. We would watch the rollercoaster while in line, know its dips, turns, and screws, but when we were actually in the moment, our plans faltered.

II

Caroline says, “Lou Reed is dead.” She slides her phone into her purse and we walk through the turnstiles and onto the rollercoaster platform. We take our seats three cars behind the teenagers. I buckle into my seat and pull the bars down across my lap and then the rollercoaster slowly clinks forward.

As the coaster climbs, ascending to the drop-off, the point of no return, I think of Lou Reed. He was my favorite musician throughout high school and college. Growing up in a conservative blue-collar family of coal miners and truckers in West By God Virginia, I always felt like the outsider. I connected with Reed’s transgressive lyrics and themes. He was my hero. I listened to “I Wanna Be Black,” read Norman Mailer’s “The White Negro,” and considered myself an American existentialist, much like Reed. His view on American culture and its losers and misfits created a sense of belonging for me.

When I first started dating Caroline, I would sing Reed songs to her. I sang “Caroline Says,” but only once. “Why are you singing a song about an abusive and doomed relationship to me?” Caroline asked. From then on I refrained from Berlin songs, relying instead on tracks from Coney Island Baby: “You’re the kind of person that I’ve been dreaming of. You’re the kind of person that I always wanted to love…”

I would drive over to her house after class in those early days and we would crawl into bed together, becoming a mess of sheets, me singing to her: “You really are a queen...” And then I would leave and she would call me and say, “I can smell you in the sheets still.” I would turn my car around and return to her house and crawl back into bed with her, becoming a mess of sheets again, crooning, “And you, you really are a queen, oh such a queen, my queen…”

But now Reed is gone. I had read about his liver transplant earlier that year and the string of cancelled performances in the months following, all signs of an ailing musician. The truth still hits hard. I wasn’t ready. It seems like a silly thing not to be ready for, a musician I never met.

After exiting Silver Bullet, Caroline and I walk to the booth selling snapshots of the ride. I pull out my phone and read the responses to Reed’s passing on Twitter and Facebook. Caroline looks to the booth and then to me. “You’re fucking ridiculous,” she says. I have no idea what she’s talking about, but then I see. In the photo, everyone on the rollercoaster is screaming or laughing, the teenagers in front of us especially, except me. I look like I’m watching Sarah McLachlan’s SPCA commercial at 60 MPH.

III

Caroline says she’s ready to go. We exit the park and return to the car. I listen to music on the ride home, she reads. As we turn off the interstate and pull into Guthrie, still thirty minutes from home, Lou Reed’s “How Do You Think It Feels” comes on the radio. Caroline looks up from her book and laughs. “Look, Lou is communing with you from beyond.”

I chuckle, too, and Caroline returns to her book. After a minute:

“Hey, Caroline?”

“Yeah?”

“Did you know Reed’s Berlin was derided by critics when it was first released? That Rolling Stone called the album a disaster? And that thirty years later they had a change of heart, turned around and called Berlin a minor masterpiece? Did you know that?”

“I think you might have told me, once or twice. Why?”

“I don’t know. I was just thinking about it.”

Caroline nods and closes her book. Lou Reed gradually fades out and I reach over and turn off the radio. We sit in silence for the most of the ride back to Stillwater until Caroline turns to me and says, “Dillon?”

“Yes?”

“You know I love you, right?”

—Dillon Hawkins