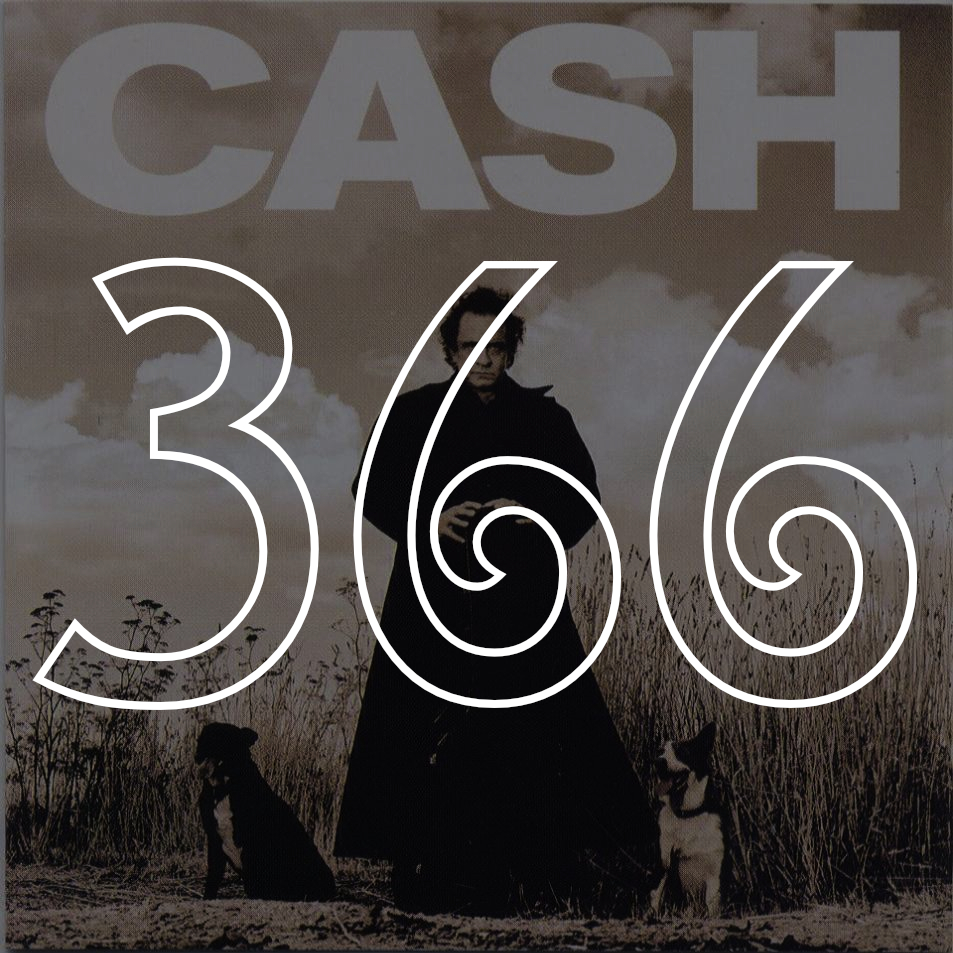

#366: Johnny Cash, "American Recordings" (1994)

Here are some facts about American Recordings that help explain the total insanity behind its existence, which one might not necessarily garner simply by listening to the music, which sounds largely if not entirely like a collection of some pretty good country songs:

American Recordings was Johnny Cash’s 81st album.

When American Recordings came out in 1994, Johnny Cash was 62 years old.

Johnny Cash made his first studio recordings in 1955, which means he’d been recording music for just under 40 years when he made American Recordings, which was his 81st album. That is a whole lot of music to record in 40 years.

American Recordings was the first in a four-album run that is across the board considered the second-best period of the across-the-board second-best country music artist of all time. At the end of this period, Johnny Cash was 70 years old. The period only ended (probably) because he died.

Rick Rubin produced American Recordings.

This one is big and weird and cannot be understated: Rick Rubin produced American Recordings.

Other albums produced by Rick Rubin within the two year window on either side of his producing American Recordings: Sir Mix-a-Lot’s Mack Daddy, Flipper’s American Grafishy, the Last Action Hero soundtrack, Slayer’s Divine Intervention, Sir Mix-a-Lot’s Chief Boot Knocka, Red Hot Chili Peppers’ One Hot Minute, Andrew Dice Clay’s Dice Live at Madison Square Garden, AC/DC’s Ballbreaker, Sir Mix-a-Lot’s Return of the Bumpasaurus.

Needless to say, none of these albums sound much like American Recordings.

Rick Rubin is (probably) the most important producer of the last 30 years, but everyone’s favorite story about Rick Rubin is still this one: when he was 17 years old, Rick Rubin got all his friends to come heckle his band at one of their shows, and also got his band to get into a brawl with his friends in response to the heckling, and also got his dad to wear his police uniform and break up the brawl, even though his dad had no jurisdiction in Manhattan, where the show was taking place. At 17 years old, Rick Rubin orchestrated local buzz around his own band by orchestrating a fake riot, which required a lot of help from basically everyone he knew and explains a lot about who he would grow up to be.

In 1993, Rick Rubin changed the name of his record label from Def American to American because he found the word “def” in the dictionary and declared it (essentially) no longer cool.

When he changed the name of his record label, Rick Rubin held a funeral for the word “def.” 500 people attended. The Reverend Al Sharpton presided. This is how the Los Angeles Times described the funeral: “Mourners followed a 19th Century-style horse-drawn hearse and a six-piece brass band playing ‘Amazing Grace’ past the mausoleum that holds Rudolph Valentino’s remains to a freshly dug grave with a simple black granite slab inscribed DEF.”

Rick Rubin held a funeral for a word and then within six months had signed Johnny Cash, who then made what would become probably the second most famous of his then-81 albums.

This is not always the case, that the facts which coalesce behind a record become the reason a record is so beloved.

That last sentence, actually, is almost patently untrue. Many, many very famous, beloved records are famous and beloved largely due to the facts behind their very existence more so than the music on the wax. Some of them, like American Recordings, are comeback albums—this makes sense, because everyone likes a good comeback album (and no one likes a bad one). Others are harder to explain: Rolling Stone, for example, considers Sgt. Pepper’s the greatest album of all time, a reasoning it explains with eleven paragraphs detailing first-hand stories behind the album’s importance and creation. Sometimes the music itself is mentioned, but pretty much always in the context of its “firsts,” rather than, say, its sonicness or sweet-ass harmonies. Another: Nevermind, no one’s favorite Nirvana album and definitely not their best, is the most famous and beloved album of a whole generation of Americans because of what it meant when it was released. James Brown’s classic Live at the Apollo is basically 20 percent Brown’s voice, 10 percent showmanship that you can’t see because you can’t see audio, and 70 percent screaming teenagers—it’s more cultural artifact than listenable record, but that doesn’t negate its bigness. The story simply surpasses, again and again.

American Recordings is this kind of collection. It’s 13 songs long, two of which were recorded live at Johnny Depp’s nightclub (you be you, 1994), the rest in the Man in Black’s literal living room in Tennessee. It documents an aging legend using only his aging, legendary voice (more legendary than aging, tbh) and an acoustic guitar. Sometimes he says fuck it and just sing-song-talks. It’s in parts both moving and nice to listen to. It is never amazing. (The closest it gets is the nearly transcendent, v funny closer “The Man Who Couldn’t Cry,” mostly effective thanks to the live audience providing laugh track to all the right parts.)

But it doesn’t need to be, not really. There are 12 good reasons at the top of this page why not, and about two dozen you could add to those. It’s one of those album where we all agree: sometimes just existing is enough. Sometimes maybe even preferred.

—Brad Efford