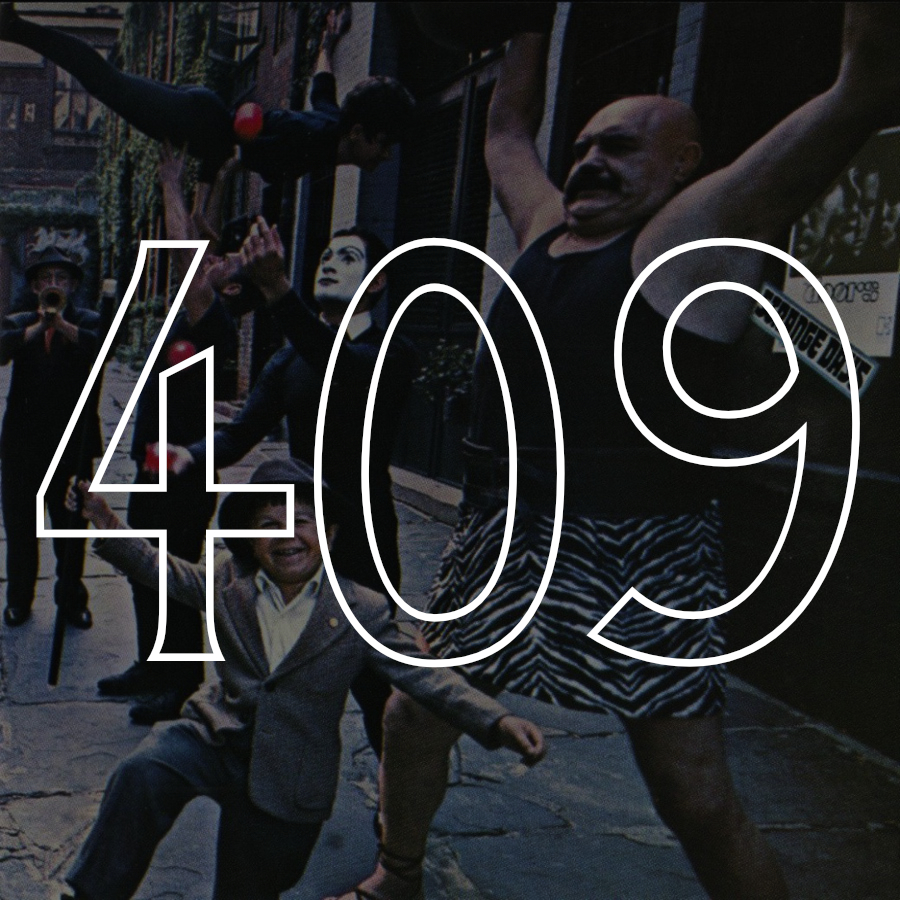

#409: The Doors, "Strange Days" (1967)

With his beaded necklace, oily ringlets, and feline glare, Jim Morrison peered over my bed throughout my years in high school. I don’t know what possessed my adolescent self to tack up this particular poster, as his melodramatic, shirtless pose embodied one of the many qualities of the Doors that I derided: the exploitation of Morrison’s charisma to maximize the band’s teenybopper appeal. But there he was, the Lizard King, Mr. Mojo Risin’, unblinking and aloof while I learned to knot a necktie, solve equations with two variables, and meander through the pentatonic scale on my Gibson. Sometimes at night, cocooned in headphones, I would rhapsodize about traveling through time to become the bassist the band never had. Gig after gig, our primal, organ-drenched vamps would entrance Morrison, beer sweat pouring through our clothes, as he prowled those stoned children in the pit. We want the world and we want it NOW. I avoided thinking about his beard streaked with grey, how bloated he looked in his last Parisian snapshots, how melancholy and deep his baritone sounded on “Hyacinth House.” Like most teenagers, I policed my fantasies for signs of consequence. Instead, in the flood of imaginary spotlights, my jazzy runs held our nightmare jams together as we careened from exaltation to madness and somehow made it back.

At the close of 1967, the Doors were America’s most dynamic rock band. With the exception of Love—their Elektra label-mates—no other California group from the late 1960s unified such a disparate range of influences and distilled them into an original, cohesive sound: blues, jazz, surf, flamenco, pop, psychedelia, chamber music, cabaret, and French surrealist poetry are all ingredients in the Doors’ cosmic stew. That the band recorded six studio albums in five years is nothing short of remarkable given their combative personalities, relentless touring, and Morrison’s various extravagancies. Their self-titled debut, released in January of that year, is the stuff of legend. The band’s sophomore effort, Strange Days—released just eight months later—is both hard to praise and hard to hate in its entirety. It is an album jarring in its uneven compositions, poor sequencing, and relative brevity (it only runs 35 minutes), yet it somehow maintains a brooding fortitude. Much like the Doors’ oeuvre itself, Strange Days is best remembered for its haunted songs of forlorn love and social disillusionment, which, four decades later, still endure as a visceral counterargument to the harmonious platitudes of the sixties.

The album’s strongest songs find the Doors unchanged in sound but far more cynical in worldview. The album’s kickoff track, the dismal and reverb-drenched “Strange Days,” made for a peculiar single, and its uninviting moodiness still renders it a poor place to start. Regardless, the propulsive bass lines from studio musician Douglass Lubahn and the song’s major-key bridge keep its uninspired melody from devolving into a rainy day personified. “Love Me Two Times” is a raunchy goodbye ballad that foreshadows the straightforward sound the Doors would discover on Morrison Hotel, which has always been my favorite among their records, as it captures them as The World’s Darkest Bar Band. “You’re Lost Little Girl,” with its subdued textures alluding to the Beatles circa Rubber Soul, harkens back to “The Crystal Ship” from their first album, with Ray Manzarek’s organ and Robby Krieger’s guitar in perfect conversation. “Moonlight Drive” is perhaps the only Doors song that is truly evergreen—it would have fit on any of their albums—the result of it being their oldest collaboration, honed by years of tweaking. Finally, “When the Music’s Over” is a gritty, growled retelling of that other ten-minute odyssey, “The End,” but lyrics of failed romance have been displaced by a mocking, self-referential examination of rock’s transitory bliss.

The bad material on Strange Days is truly bad, and only matched by The Soft Parade—the Doors’ one true flop—in terms of its inanity and disposability. I’ve never been able to fathom why “People Are Strange” has endured as one of the Doors’ iconic songs since it sounds like it was written by a twelve year old, and they perform it with the hesitancy of a cover band playing their first frat party. Campy and obnoxious, it begins as a show tune and ends as pub singalong. “Unhappy Girl” and “My Eyes Have Seen You” strain toward goth-pop, the latter of which sounds like a rip-off of the Zombies. “I Can’t See Your Face in My Mind” is too wispy and repetitive to be a successful song, which make it the stereotypical deep album cut that most listeners skip whenever the >> button is within reach. Last and certainly least is Morrison’s spoken-word poem “Horse Latitudes,” rendered with such mawkishness that it is impossible to take seriously. To this day, its hokey sound effects remind me of the Trojan rabbit catapulting over the castle’s parapet in Monty Python and the Holy Grail.

As a lifelong fan, I’ve accepted that the Doors’ legacy is equal parts muck and magic, but reading Stephen Davis’s Jim Morrison: Life, Death, Legend in the fall of 2004 gave me context and compassion for the band’s various blunders. From Oliver Stone’s bombastic 1991 film to that starry-eyed book of myths No One Here Gets Out Alive by Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugarman, the Doors have always suffered from a lack of credible biography. Davis’s critical and objective meditation filled the gap. I read his book a year after visiting Morrison’s grave in Paris on a drizzly day of sightseeing with my friend Andy. My most vivid memories of that long, melancholy afternoon are study abroad clichés: trying to decipher a cartoonish city map written in French, searching out a lunch we could both stomach and afford, and shuffling through Pere Lachaise Cemetery with rain-sogged shoes. The following fall, I breezed through Davis’s tome on Sunday afternoons reclined in the tub of my drafty Toledo apartment—the grim irony of Morrison’s body being found in his bath escaped me—soothing the war wounds I earned playing pick-up football with my grad school pals. The bathroom’s emerald tiles glinted in the autumnal light, relics from the gaudy decade about which I was reading.

Suds-covered, groggy, and bruised, I finally saw the panoramic sweep of Morrison’s confliction and the band’s perseverance in the face of constant skirmishing. A bourgeois military brat, his childhood relocations left him a detached, habitual liar. (In his early interviews, he tells reporters that his entire family is dead.) Morrison’s secretive bisexuality compromised his ability to form relationships, and his covert liaisons were often a liability for his bandmates and their handlers, as their fortunes relied in no small part on his heterosexual machismo. Most significantly, by the time he was in his early twenties, Morrison’s alcoholism was the central force in his life. A dabbler in psychedelics, booze was his disease, and his adulthood was a prolonged drunkenness punctuated by brief moments of sobriety in which he wrote poems of naïve promise. In that tub, my silly, anachronistic yearning to be the band’s bass-slung backbone morphed into a young man’s appreciation and pity. When I closed my eyes and drifted off, I imagined Manzarek, Krieger, and Densmore wincing on stage amid the feedback squall, the slurred lyrics echoing through their monitors, and the manic adulation of fans who kept their arms outstretched in the arena’s clammy darkness. The band wore the shadows of Jim’s spoiled tragedy. Hunched and solemn, they shut their eyes until he howled again—bestial, unknowable, midnight’s clown.

—Adam Tavel