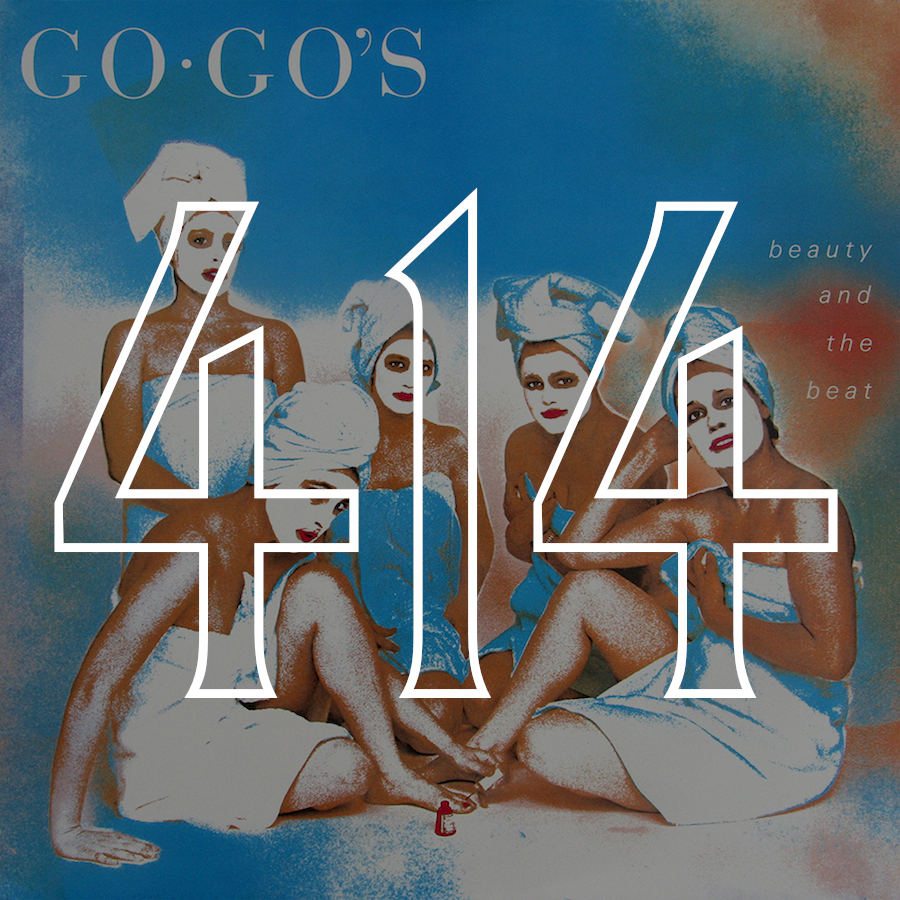

#414: Go-Go's, "Beauty and the Beat" (1981)

I was eleven when my parents divorced, which was just old enough to appreciate the fact that the house was quieter without their constant screaming at each other, but young enough to still feel that it was my fault. My father took me out for ice cream the day after my birthday, and as I was trying to lick the peppermint bon bon off the edge of the cone before it melted into a puddle on my hand, he told me that he’d be moving out, thereby taking a hammer to the mirror that was my world and smashing it into pieces. The peppermint bon bon dripped and dripped, and I cried, and my dad said, “Cynthia, this doesn’t mean I don’t love you,” and then he went inside to get more napkins to clean me up.

The next weekend, my dad moved out of the house he’d shared with me and my mom and into an apartment with the woman my mother referred to as “that skank” when she thought I wasn’t listening. The woman herself told me to call her Ella. I spent every other weekend with Ella and my father at his new apartment, which smelled like mold and old Chinese takeout, and which didn’t even have blinds over the front windows. My father gave me Sharpie markers and a coloring book, like he thought I was still five, and my mother was furious when I got home, because I’d managed to mark up my T-shirt.

Illustration by Annie Mountcastle

I tried to hate Ella, but I was only a kid and incapable of nursing a grudge the way I can now. She bribed me, and I fell for it. She gave me barrettes and braided my hair and told me I was going to be a rock star in middle school. She wanted to know what books I’d read, what movies were my favorites, what kind of music I liked. She took me to the library and we went to Saturday matinees at the cheap theater, where they still made their popcorn with real butter. When she found me singing along to her Go-Go’s record, she went out and bought me the CD. “Now we can sing in the car,” she said. She helped me put my hair in a side ponytail and did the same to her own, and dressed us both in baggy, bright sweatshirts and pronounced us ready for the 80s. “You’re going to grow up and make history, too,” she said. “Be a badass female. You won’t be able to help it.” I liked when she spoke to me like that, like I could do and be anything.

When I got home that Sunday evening, I played the CD in the boombox I had in my bedroom. I kept the volume low, but my mother heard it anyway and came in. She didn’t knock. She never knocked anymore.

“Where did you get this?” she said.

“Doesn’t matter what they say,” Belinda Carlisle was singing, “in the jealous games”—and then she fizzled into nothing as my mother hit the eject button.

“Where did you get this?” my mother said again. I mumbled something about borrowing it from a friend, but my mother said, “It’s from her, isn’t it? She thinks she can paint your nails and do your hair and be your best friend and I won’t notice. That skank,” she almost screamed, and I was surprised, because that was the first time she had ever called Ella that when she knew I could hear. My mother took the CD in her hands and snapped it in two, and the sound it made as it cracked seemed to echo through my bedroom.

My mother began to cry and say how sorry she was. She sat down on my bed and patted the mattress next to her. I didn’t want to be near her, but I sat down anyway. She was still holding the pieces of the CD. It had split perfectly down the middle. “I need you to do something for me,” she said. “Can you do something for me?” I nodded. “I need you to tell your father that you don’t like Ella,” she said. “I need you to tell him that you hate her, that if she’s there, you won’t go see him. I need you to make him believe you. Can you do that?” She leaned forward and her hair covered her face and she made a honking sound as she tried to blow her nose into her sleeve, something she’d always told me never to do.

I was only eleven, so I didn’t yet understand how love can make you crazier than you ever thought possible, how it can grab you with its teeth and thrash you back and forth to break your neck, how by the time it releases you, you don’t know who you are anymore. I hadn’t yet lain awake at night feeling like my stomach was twisting out of my body. I hadn’t moved out of apartments, switched grocery stores because I couldn’t stand to be in the same place where I had once been happy. I hadn’t cried so hard it sounded like screaming.

I didn’t know that my father had been sleeping with Ella for years while still married to my mother, that he’d known her longer than my mother, that he’d almost called off the wedding because he’d known he didn’t love my mother. I didn’t know that my mother had been calling him every night, alternately cursing him and begging him to come home. I didn’t know that he answered each time she called, that he called her honey and said that of course he loved her, he just couldn’t be with her, leading her to believe that she still had a chance. All I knew was my mother wouldn’t stop crying, and she had given herself the hiccups, and she had broken my CD, and I wanted her out of my room.

“No,” I said.

“What?” she said.

“That’s mean,” I said. “You’re mean. I won’t do it. I wish I lived with Dad and Ella. I want to live with Dad and Ella!”

“You don’t mean that,” my mother said. “Cynthia? Do you mean that?”

And then I did the cruelest thing that I have ever done. “I hate you,” I said to my mother. “I hate you!”

Illustration by Annie Mountcastle

It wasn’t the first time I had said those words. When you’re a child, you can say them for anything: no dessert, no second underdog on the swing, no sleepovers on a school night. But this was the first time that I meant it. In that moment, staring at my mother’s blotchy face, the CD pieces still in her fingers, the pale white line that marked where her wedding ring had always sat on her finger, I hated her.

My mother stood up carefully, like she was afraid she might break something if she moved too quickly. She set the pieces of the CD down on my bedspread. I didn’t touch them until she’d left the room. I tried to fit the two pieces back together, but I couldn’t. Some little tiny chip had come free when she’d broken it, had gotten lost in the weave of the carpet, and when I placed the pieces next to each other, it proclaimed itself by its absence.

I didn’t move in with my father and Ella. My mother and I never mentioned the conversation we’d had. She stopped calling Ella “that skank.” She stopped talking about Ella at all. I still spent every other weekend with them, but when Ella tried to braid my hair, I flinched away from her. When she asked me about my life, I shrugged.

As it turned out, Ella left my father just two years later. She stopped by to see me on her way out of town. She told me that she was sorry we hadn’t been able to stay close. She told me that I was still a rock star. She told me that she hoped I’d remember her when I was older. Then she reached her hand out like she was going to hug me, a squeeze across the shoulders maybe, but instead she let it drop, and she turned around and got into her blue sedan and drove away.

I went back inside, where my mother was waiting. She didn’t say anything, just watched as I went past her up the stairs and into my bedroom. My window overlooked the street in front of the house, but when I pulled back the curtain, Ella was already gone. I had thought that I would feel sad, but as I watched the front yard, where the tire swing my father put up for me when I was little was swaying back and forth in the breeze, I didn’t feel much of anything.

—Emma Riehle Bohmann