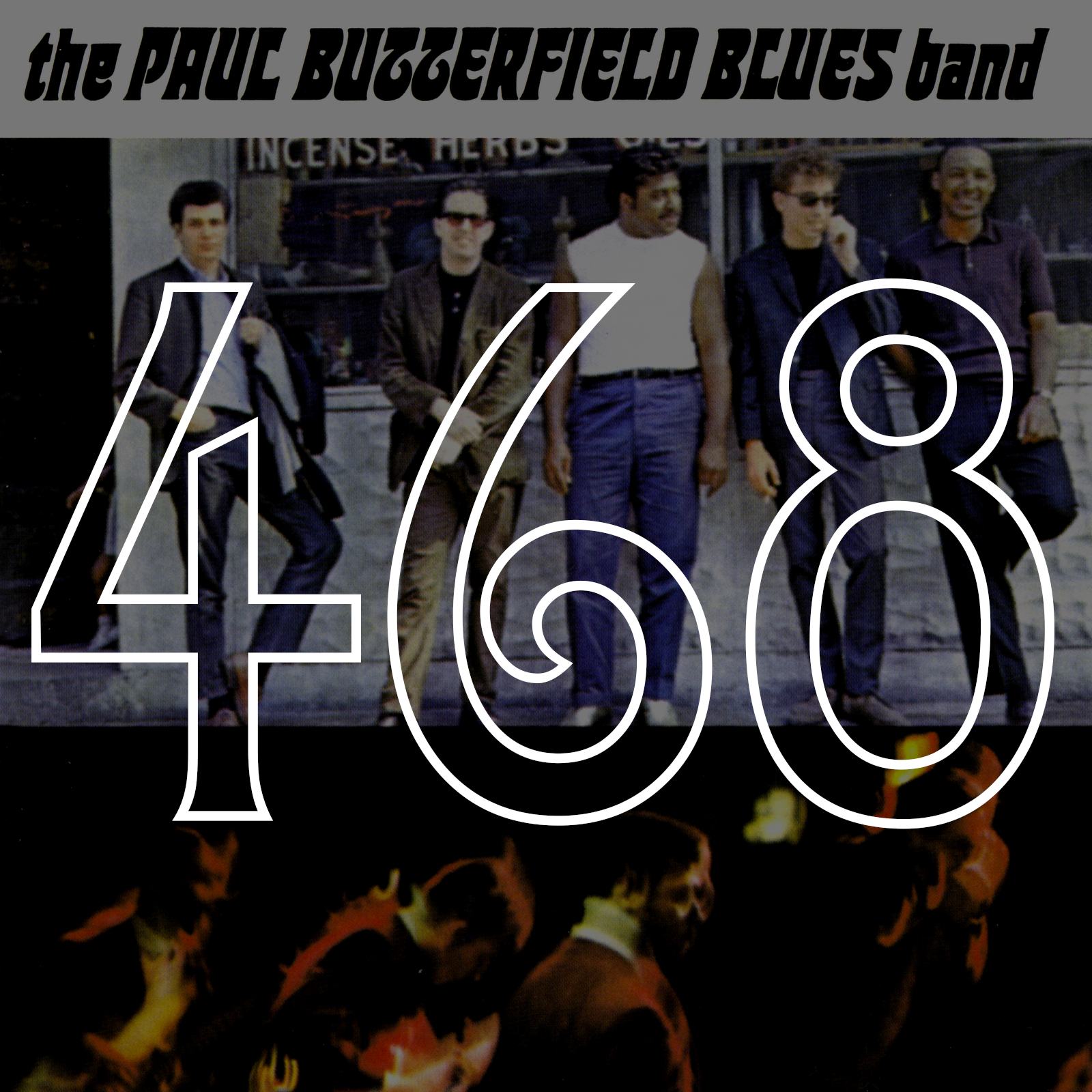

#468: The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, "The Paul Butterfield Blues Band" (1965)

There's a great video I've just come across of Michael Bloomfield and Son House giving separate, edited-together interviews during the 1965 Newport Folk Festival.

Bloomfield was, at the time, the 22-year-old guitarist wunderkind for the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, and Son House was, even then, one of the greatest living bluesmen in the history of recorded music—he would have been 63 in the summer of '65. Both men are dead now—Bloomfield in 1981 at the supremely young age of 37 (drugs), and Son House years later, at the much more respectable age of 86 (cancer of the larynx, a singer's nightmare). Anyway, the video is a real trip to watch. It keeps cutting back and forth between the two men: one very clearly representing the new upstart vanguard of white blues guitarists, and the other what most who care about this kind of thing would still consider a flag-bearer for "real," "authentic" blues. Bloomfield, to his credit, admits that he basically has no right playing the blues, or at the very least, calling what he plays "the blues." He's from a very well-to-do background ("My father's a multi-millionaire, y'know? I've lived a rich, fat, happy life, man. I had a big bar mitzvah, y'know?"), which he speaks about as if it were some cosmic joke that he should ever have been born into such a scene.

Still, what can playing the blues possibly mean to him, beyond just hitting guitar strings in an aurally pleasing way? What can it mean to any white man? Or any person so financially secure at such a young age? Does color matter? Should it? Rock 'n' roll critics have been flailing around helplessly in some attempt at answering these questions for 50-plus years, I know. But still.

And, too, just to complicate shit: Bloomfield himself, while alive, seemed to flip-flop on his own specific connection to the music. In this video, he passes over his Jewish upbringing as a way to flippantly explain why the blues couldn't possibly be his to possess. "It's very strange," he says, "'cause I'm not born to blues, y'know? It's not in my blood, it's not in my roots, in my family, man. I'm Jewish, y'know?" He laughs, and the faceless interviewer laughs with him. "I've been Jewish for years."

Then later, as that very young man got a little less young and much more famous, he went on record giving that same Jewishness as reason for his ability to truly know the blues after all: "It's natural. Black people suffer externally in this country. Jewish people suffer internally. The suffering's the mutual fulcrum for the blues." And maybe he's right, in a way, but is it really the same? Could the blues really just be a channeling of the suffering of a whole people, even if the one expressing it hasn't experienced said suffering himself? I don’t know. Maybe.

But check out Son House in this video. He isn’t being interviewed physically alongside Boomfield, but you get the distinct impression of what he thinks of the young man, or at least what he represents, that House’s own thoughts on the subject of race and authenticity and the blues are that of an old-timer stuck firmly in his ways. The thing is, you could easily argue that these ways are very much the right ones to have. After all, Bloomfield does insist that he’s “no Son House,” and when you watch the elder bluesman play, you get what he means without him having to explain in the least. It’s all there in the way House’s right arm flaps like a bird with a busted wing-bone and his left one herky-jerks up and down the neck like it’s trying to catch that bird and throttle it. The whole blues narrative we’ve come to know, right there before us: eyes closed, swaying as though possessed.

I’m simplifying to make some semblance of a point, obviously, which is to wonder if the blues was ever—could ever—be intended for a white audience and white musicians. And if white folks get bluesy, if they get into their licks and start swaying in the crowd, is that inauthentic? Or just some other kind of possession? Some totally other kind of music?

I know I’m not the ideal person to be writing this—I’m not black, not even Jewish—but does that fact in itself make the questions, the observations, inauthentic? Maybe even totally void of an argument? Moot, as they, completely beside the point. I can’t answer that, I don’t think (though the answer, probably, is yes, absolutely).

So, what, then? I listened to The Paul Butterfield Blues Band like three times, and then it got boring, just those same 12 bars on and on, the same high-flying solos tossed in between. And then I thought, but is that their fault? Maybe the blues just never should have been Butterfield’s bag. Maybe when, in the video with Son House, Bloomfield swears up and down that his band’s frontman is “in there all the way,” that “there’s no white bullshit with Butterfield,” it’s just a 22-year-old kid who likes playing his guitar and promoting his new band. It’s not impossible. (In fact, both things, I’d say, whether or not they negate his authenticity, were pretty much undeniably true.)

This record came out in 1965, and is considered one of the first blues albums to prominently feature a white singer, after The Yardbirds first toured, yes, but still just before Fresh Cream and a few years before Zeppelin I (or II, or III…). I guess, in a way, that means it was before its time. But is its time worth celebrating? Take one look at Rolling Stone’s 500 Albums and it’s clear how riotously they continue to celebrate it. Would Son House be cool with that? Does it really make a difference? (No, and okay, yes.)

—Brad Efford