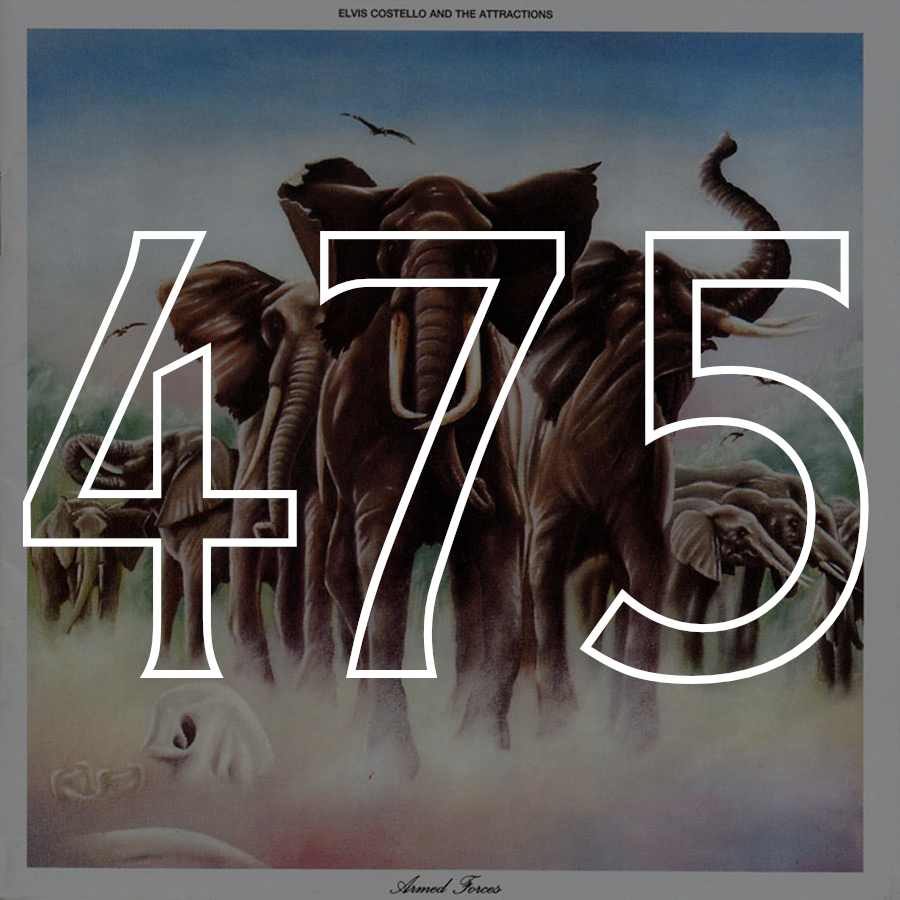

#475: Elvis Costello and the Attractions, "Armed Forces" (1979)

Dear Women For Whom I Made Mixtapes Between the Years 1996 and 2005:

I’m 38 years old, which plants me firmly in middle age. You too, I suppose, although when I think of you all, you are still your twenties selves, past the naivety of the teenaged years but not yet into the carried weight of our thirties, with its mortgages and retirement funds and, for some of you, children.

If you’re like me (and I suppose that romantic pasts imply at least a little similarity between us), then nowadays, you think often about being older. There are the regrets of recognizing that certain avenues are closed off, of what might have happened if only someone had said or done a certain thing. There’s the realization of doing old-person-type things for the first time: wincing at how loud a movie is, starting a sentence with “nowadays.” And there’s gratitude, too, a thankfulness for having grown up in the time that we did, an understanding of how lucky we were to feel the wind in our hair while riding a bike helmetless, how lucky we were to have found out what sex was slowly, rather than discovering all its possibilities and terrors from the front page of RedTube.

Music was a physical thing for us, too, sold in stores and through 12 CDS FOR A PENNY magazine ads. We had mixtapes, first on cassette and later on CD. I miss them a lot. My friends now do year-end playlists on Spotify and in .zip files, and I download them, but I miss the joy of opening the mail to find that package bulging with possibilities, a tape or disc of songs I knew, songs I didn’t know, songs about which I’d only heard rumors.

(I know that I am in full nostalgia mode with you now; forgive me. I’m not prone to thinking about you, happily married as I am, but I have never made my wife a mixtape, and so this territory is yours.)

But those mixtapes were fanboy-to-fanboy, designed to wow and amaze not with emotion but with rarity. Unknown bands and the B-sides of import singles, the results of digging through racks of CDs in used stores until the tips of our fingers were black from a slowly accumulating dirt, digging for that which we knew had never been heard—these were our pursuits before Napster came along and rendered it all irrelevant. Once you could download someone’s entire collection in a few hours, the point of those racks vanished.

The mixtapes for you, though—they were an art unto themselves. I labored over them for hours, far beyond the 80 or 90 minutes that the formats could hold (never the 120 minute tapes, which held so much that they would eventually, too soon, break under the strain; I’d make a metaphor of them and our relationships if I’d used them, but I didn’t). I would stand in front of my collection and think carefully about what I wanted the tape to say about me. Then, I’d cue a song, press record, and begin.

Because this is what I believed about myself in those days: that I was what I consumed. What I watched, what I read, what I listened to most of all—these were the things that I believed I was. This is why I worked so hard on those tapes—because I was giving myself, I thought, to you. This is why I have never made a mixtape for my wife.

When I think of you, I am sorry for things—sometimes for how I treated you, and sometimes for believing in you. I am sorry for my youthful pretension, and most of all in that pretension, I am sorry for all the Elvis Costello songs on those mixtapes. You see, I loved him, all of him. In my collector’s obsession, I tracked down the reissued albums (the ones with all the bonus songs), the limited edition EPs and box sets, the albums he did with country musicians and jazz musicians and even the terrible concept album with the string quartet. You saw me in contact lenses in those years, but when I took them out at night, I wore glasses like his, glasses that are in fashion in 2014 but felt like my secret connection to him back then.

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

I’m sorry for the Elvis Costello songs not because they are bad music—I can make a great argument for his first five albums and a decent argument for the next seven. I’m sorry because they’re songs about being a young man motivated solely by jealousy and lust (as Costello said he was in those days), and because I decided that four or five minutes of my love letters to you needed to be occupied by that.

The original title of his third album, Armed Forces, was Emotional Fascism. I knew that, and I still thought that its songs stood for me. I saw the cover art, tinted green through the trademark Rykodisc CD case, and its stampeding elephants felt like my heart, charging forward. It’s only now that I realized they were trampling everything in their path.

The cover art didn’t matter because I didn’t put the cover art on the tape. What mattered were the songs you heard, and they’re wonderful songs—the leadoff of “Accidents Will Happen” (“used to be a victim / now you’re not the only one”) into Steve Nieve’s majestic piano chords ringing out in “Oliver’s Army” (I would rather be anywhere else / than here today”). “Party Girl” and “Moods For Moderns” and closing the album with “(What’s So Funny ‘Bout) Peace, Love and Understanding”—the whole album is tightly wrought with furious playing and sneering lyrics and a stance of defiance that resonated so strongly with me that when I heard them, my body felt like a bell had rung right next to it.

That undercurrent, though, of resentment and fear and disdain (“you can please yourself / but somebody’s gonna get it”)—that should have been a warning to us. A warning that I didn’t know what I was doing, a warning that I too might have been far motivated by jealousy and lust than I understood. Fascism requires a fanatic audience, and I was ready to put on the uniform.

I should have put Armed Forces aside. I should have put on an extra R.E.M. song, or something from Nirvana’s Unplugged, or something that said anything besides I am capable of terribleness in love. I didn’t. But regret is another middle-aged tendency.

I still listen to Elvis Costello now, but I don’t need him the way I once did. Something’s changed, maybe in me, maybe in him, maybe in the way neither of us is an angry young man these days. After Armed Forces, Elvis Costello and the Attractions made a twenty-song tribute to their love of American soul music called Get Happy! These days, it’s my favorite of his albums. It’s not me, though. I get that now.

As I get older, I find nostalgia’s pull a strange thing. I hear music I hated in college and feel a joy in remembering those days of hating it. And so even though you and I didn’t end well, for whatever reason, I hope that if your Pandora station brings up “Chemistry Class” or the spectacular live version of “Accidents Will Happen,” you think of good times. Like Elvis sang on a later album, I hope you’re happy now; the difference between me and him is that I mean it.

Sincerely,

Colin

—Colin Rafferty