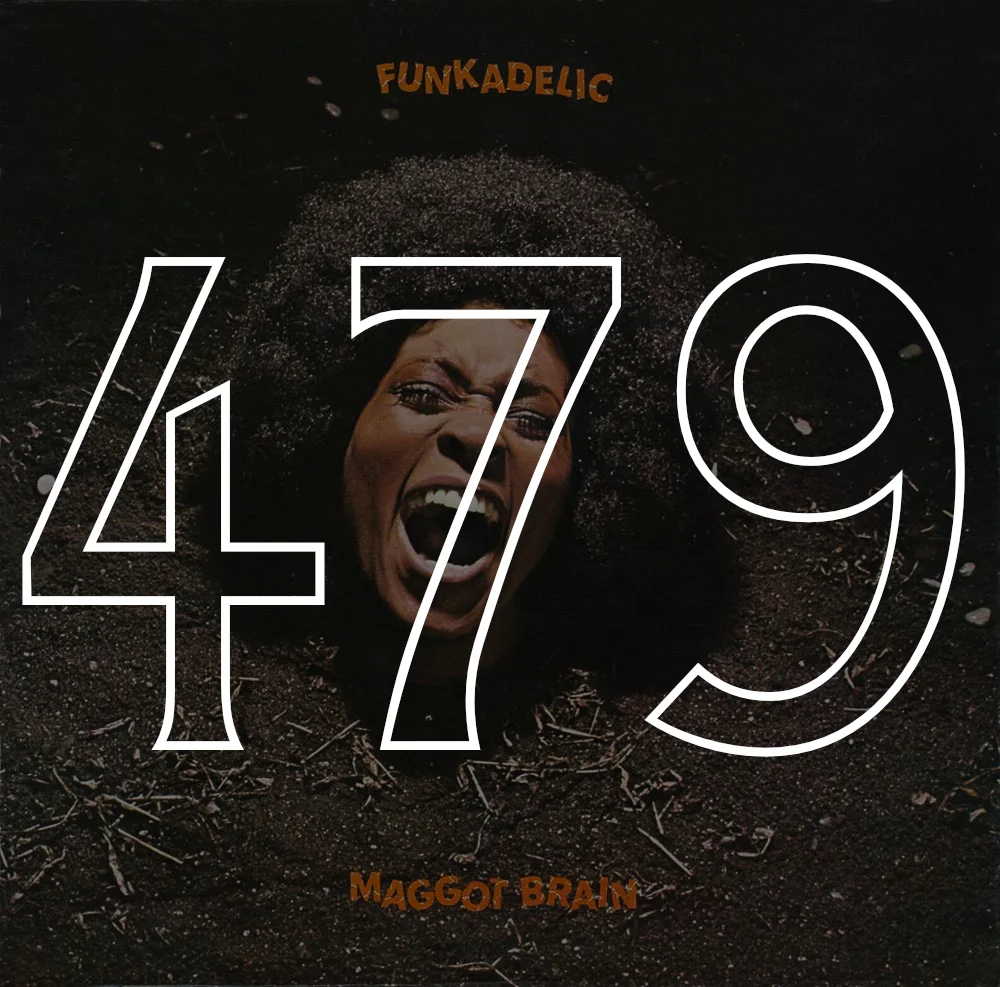

#479: Funkadelic, "Maggot Brain" (1971)

Arizona, 1974

It’s a viciously hot afternoon in Phoenix, Arizona and I’m driving with my mother to a large bank downtown where important transactions happen. We’ve passed a cigar store Indian on the sidewalk and crossed Van Buren Avenue, poor and down-trodden then as today. Vietnam’s nearly over but in our household you’d never know it had begun. We are isolated, insulated, and air-conditioned. Inside the bank, I hear the cool click of her heels on the tile floor. She means business. A mural behind the teller depicts stagecoaches, copper miners, and an ever-westward expansion into endless wealth and prosperity. There’s something in the safe deposit box my mother needs. A deed of trust.

On the ride home, my mother lets me turn the dial on the AM radio. Neither of my parents ever share much of their taste in music. They own a record player that will unceremoniously disappear one day and a few Dave Brubeck albums I never hear my father play. In the living room, my mother occasionally reads sheet music and plays the organ; she makes everything sound like church. What do we hear that afternoon, desert light streaming through the station wagon windows? I’m six-years old and hopeful the randomness of radio will offer up The Captain and Tennille’s “Love Will Keep Us Together,” or “Brandy (You’re a Fine Girl),” or Sammy Davis Jr. singing “The Candy Man.” I could turn and turn the circular dial through the infinite bland of AM pop and never hear a sound like Funkadelic.

Eddie Hazel’s Mother

Eddie Hazel, the lead guitarist on Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain, a seriously guitar-driven album, was born in Brooklyn but his mother moved the family to Plainfield, New Jersey, supposedly to limit the influence of the big city on her son. Without knowing it, she’d moved Eddie within the radar of George Clinton and his doo-wopping Parliaments who would later break all the rules and cross all the musical lines as Parliament/Funkadelic. Hazel was only 17 when Clinton tried to recruit the guitarist for a tour. Hazel’s mother refused the invitation on her son’s behalf, but Clinton was persuasive, a performer, and managed to change her mind. Eddie Hazel entered the world of rock ‘n’ roll and would be dead by age 42.

Maggot Brain and “Maggot Brain”

The legend goes that when Funkadelic went to record “Maggot Brain,” the album’s title track, Clinton told Hazel to think of the saddest thing he could imagine. Hazel imagined his mother’s death and launched into a 10-minute mournful wail of a guitar solo. You can’t dance to it; you can’t hum it. Like all things Funkadelic, the song emerges from its own world, opening with an odd voice-over, the song’s only lyrics, which are finished in the first 30 seconds of a 10-minute song:

Mother Earth is pregnant for the third time / Y’all have knocked her up. /I have tasted the maggots in the mind of the universe / and I was not offended /though I knew I had to rise above it all / or drown in my own shit.

Maggot Brain’s seven tracks move between psychedelic trance, crunchy rock, and even acoustic-laden folk. “Can You Get to That” features a rhythm guitar line pulled from the children’s song “The Old Gray Mare.” The up-tempo “Hit It and Quit It” riffs on James Brown but pulls the Godfather squarely into the rock arena. There are no horns on Maggot Brain.

These days, musicians can do anything: bands slip in and out of identities between different releases; players move between side projects with fluidity and fewer legal ties to single record labels. With so much music available on the Internet, songwriters sample past styles with ease. If we take such freedom for granted, bands like Funkadelic deserve some of the credit: they took the chances, writing the songs they wanted to write, finding an audience that was willing to follow their way of taking it to the stage.

Mothership Connection

The first song on Funkadelic’s self-titled debut album was called “Mommy, What’s a Funkadelic?” The most far-out Parliament album was “Mothership Connection.” Other tracks included titles like “Music for My Mother.” “Cosmic Slop” features the refrain, I can hear my mother call / I can hear my mother call.

What’s with all the mother talk?

The secret of funk is that the music draws from tradition as much as from psychedelic and sonic experimentation. Funk is about freedom, about crossing lines. You can’t blend sounds (funk it up) until you know your traditions. George Clinton knew how to make something of musical connection and contradiction. He grew up in the doo-wop era; Parliament and Funkadelic always showcased great vocal harmonies. The funk of the early 1970s wasn’t just party music; it was the sound of burning cars and broken windows. The music on Maggot Brain sounds like a music that knows people are dying. Vietnam is raging and there are riots in the street. How can the music not absorb this? Something’s dying from the past as well, and Funkadelic carries those doo-wop and folk sounds forward even as the band knows it’s moving away from a home to which it can’t return.

*

For their 1974 album, Standing on the Verge of Getting It On, Hazel wrote most of the songs, but he gave the song-writing credits to G. Cook: Hazel’s mother, Grace Cook. Funk was always trying to get back home, even when that home was lost.

Eddie Hazel’s obituary in The Village Voice said that Hazel “raised guitar playing to aristocratic heights through shamanistic means.” When he died, they played “Maggot Brain” at his funeral.

Music for your mother. Can you get to that?

—Keith Ekiss