#482: Steve Earle, "Guitar Town" (1986)

There’s not a lot of room in my life for country music. I like folk, and pop, not to mention the numb, unconsoling murmur of Swedish alt rock. Sometimes I jam out to 90s confessionals—Nada Surf. Something Corporate. Hey, It’s a Shame About Ray. Stacks of CDs clump in tiny Trump Towers in the foot wells of my car, in amongst the socks and receipts and forever-damp umbrellas. But not one of them is country.

Where I live, in your typical New England landscape, trees crowd close, and it’s a slow, bright creep until winter, when the leaves drop and you can finally see the sky. A daily commute around here might contain the right number of cows and barns and agile steeds to suit a Midwestern ballad, but the barns, mostly for drying tobacco, are in poor repair from disuse, and their support walls have warped like wet paper, giving the whole sloppy scene a lop-sided, fun-house mirror mien.

Instead of cowboys we have tax accountants, slumped over their steering wheels, breathing their soft animal breaths as they flock to the city. There are no quiet streets, no lonesome roads until well after midnight, though the local Starbucks closes at 8 p.m. on Saturdays, and the parking lot of Double Take Double Take Consignment is deserted by mid-afternoon. Still, there are people everywhere you look, taking silent walks down the bike paths at lunchtime, or else making urgent purchases at Benny’s Deli, stomachs clamoring to be fed. At half past five the neighborhood swells with the chatter of traffic. Dogs come out to reunite with their own front lawns. Governed by instinct, I drop my eyes as the Kauffmans march past, little Benjamin, mute with protest, sulking in his red wagon as it trails them.

To tell the truth, I don’t think country music is lonely enough for a place like this. Country music is all about isolation due to a lack of proximity; New England is isolation due to intimacy. The only way to live, when your neighbor’s bedroom is 12 aerial yards from your own, is to not know him at all. How else can you keep your edges clean, and stand fast in your enchantments?

In the Grammy-nominated title track from his 1986 album, Steve Earle promises to “settle down” and take his girl back “to the Guitar Town.” There aren’t any Guitars in the United States (I checked), but if there were, I think the reality might disappoint. According to the song, Guitar Town is just another place where “nothing ever happen[s].” Sure, there’s the siren song of a “lost highway” leading out of town, but there’s nothing appealing about highways. At least, there shouldn’t be. They’re cracked, strewn with garbage, and generally overrun by a cavalcade of businessmen jonesing for smokes. If the strangled lanes of the interstate sound like liberation to you, maybe you should head for somewhere new. But it doesn’t mean things will get better.

Just as country music romanticizes the open road, so too have Americans lathered suburbia with all the fancies of misdirected love. There is just no reason for it. The fewer people there are per square mile, the happier those inhabitants become. We may say there’s comfort in numbers, but mankind exchanged the herd mentality for something leaner long ago.

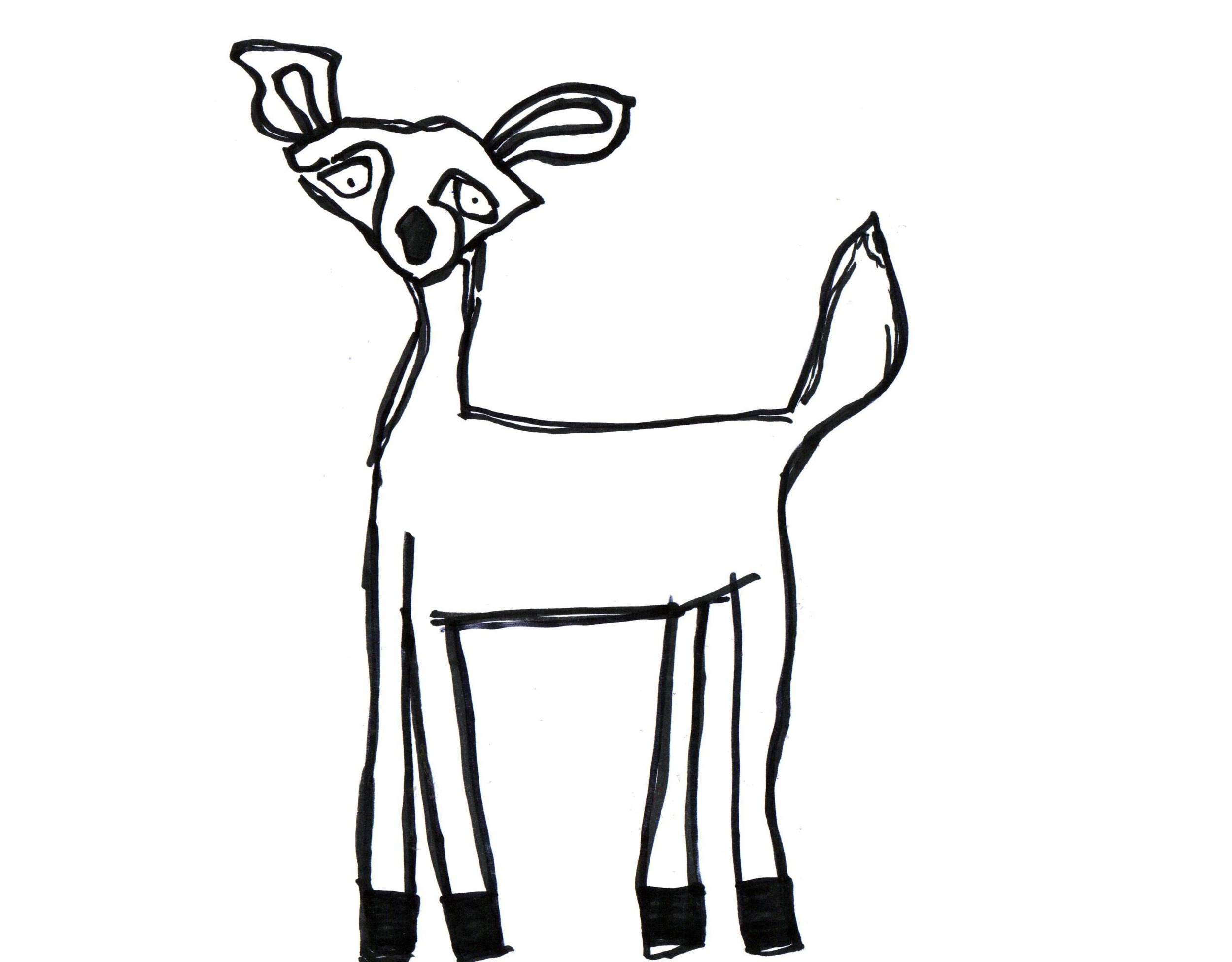

Illustration by Annie Mountcastle

Take deer, for example. Have you ever seen a herd of deer traveling together (with their little deer valises)? First there is nothing but a thin mist spreading through the trees, the shuush-shuush of your ponytail as it swings against your jacket, the precise sound water makes opening around stones. Even this is enough. You are the loudest thing here; a chipmunk shrinks from your thunderous approach. You still, hoping to appease him, when suddenly they are upon you, flashing past on the left, or the right. Everything narrows to the heat and noise. They are a hot wind. An open vein.

You become invisible in those moments, frozen like the chipmunk, too insignificant to fear. This is where freedom comes from. But in suburbia, the deer travel in twos and threes. They step sweetly through untrimmed grasses, growing stern when approached. A sharp stamp has sent me veering more than once. Deer, like the neighbors, keep a close eye on you. Do I sound like I’m kidding? I’m not.

Don’t get me wrong; I love my neighbors, and I’m pretty sure they would call the paramedics if I fell and I couldn’t get up, but you don’t love something because you need it to feel safe. And you don’t settle in Guitar Town without weighing the delicate ferocity of a deer’s footstep. You don’t forget what it feels like to run.

—Eve Strillacci