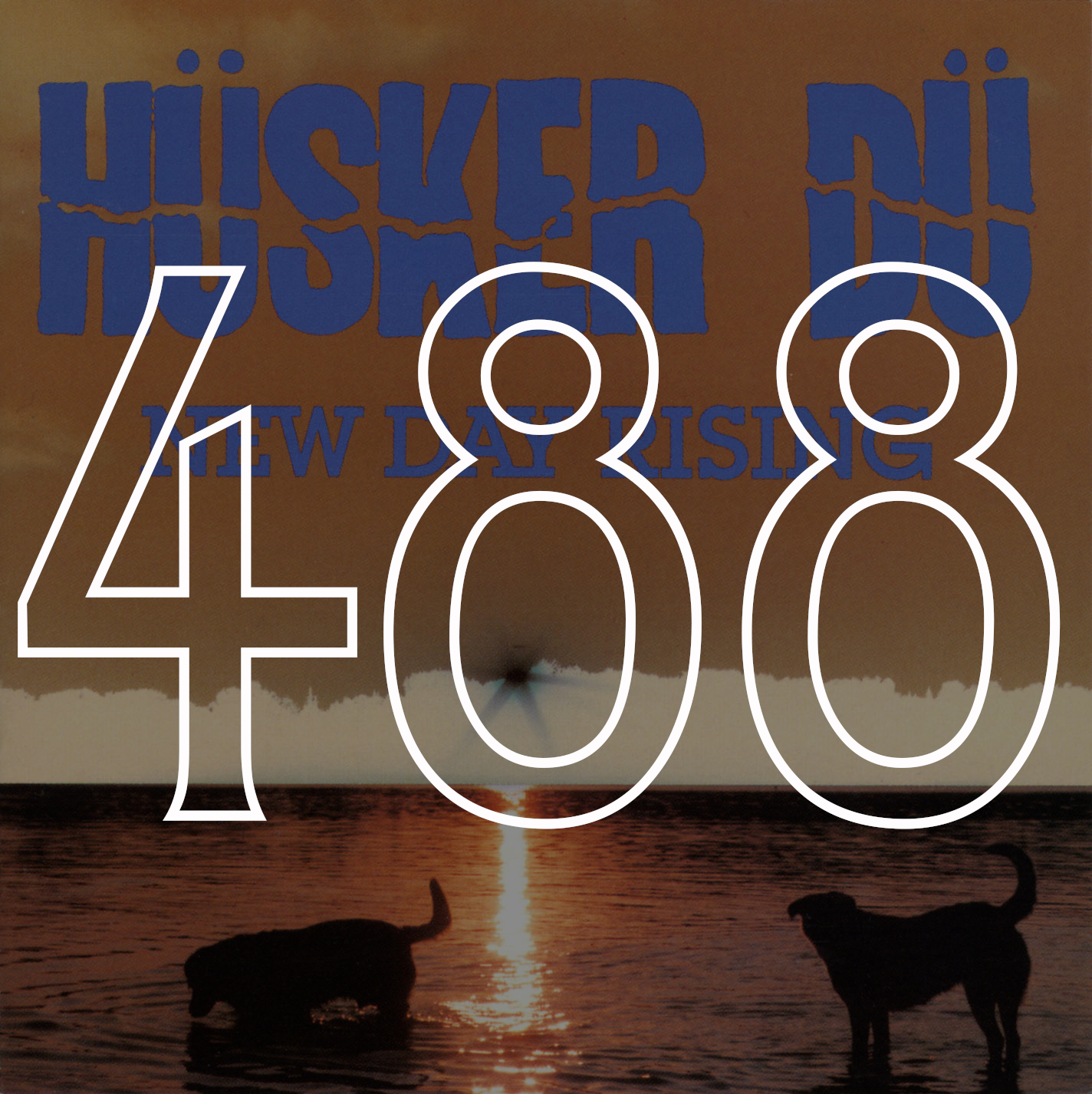

#488: Husker Du, "New Day Rising" (1985)

Mary Richards bolts her door at 119 North Weatherly and, after hanging up her coat and setting her shoes neatly beside each other in her closet, turns off most of her lights so the neighbors don’t know she is home. This is long after Rhoda moved out to New York, after Phyllis moved to San Francisco, after Lou Grant died, after Murray’s novel won a Pulitzer, but before Mary meets her future husband, Congressman Steven Cronin, and moves to New York. Mary walks on her toes so her downstairs neighbors don’t hear her, and when she turns her television on, she sits close with the sound low. Mary Richards does these things because her neighbors make her uncomfortable. She doesn’t like that this is the case, but it is.

The girl upstairs is bookish and vague, nice enough, but awkward. Mary met her a few months back on a Saturday, right after the girl—whose name Mary can’t remember for the life of her—moved in. Mary held open their building’s exterior door for the girl, whose arms were full of books. With the warmth she was known for when she was producing the nightly news at WJM, Mary asked the girl what she was reading, and the girl said, “Books,” and hurried up the stairs to her attic apartment. Later that day, bored with the sports and movie matinee options on her television, Mary made a pot of coffee, poured two cups, arranged a plate of wafer cookies and carried the spread upstairs to the girl’s apartment. She balanced the tray in one hand to knock on the door. After a moment, the girl opened the door. Mary was taken aback by the room’s darkness. She said, “I brought some coffee.” She said, “You’ve lived here long enough, I thought we could get to know each other.” The girl said, in a small voice, “I guess.” The girl said, “You can come in.” Then again, “I guess.”

Inside, the young woman neither invited Mary to sit nor offered a place for the tray. Mary started to set the tray on a stack of books. The young woman said, “Wait,” and moved the books to the floor. Mary set the tray down, and smoothed her skirt behind her as she sat on a small, plush chair, covered with a black sheet. Mary asked after the girl’s interests. The girl didn’t answer immediately, and when she did, she didn’t quite answer the question. She said, “Did you know there are approximately 200 UFO sightings reported every day.” Mary said she didn’t know that. She said, “So you’re interested in UFO’s?” The girl nodded her head, then said, “Kenneth Arnold’s 1947 sighting was the first to be shared with a large audience. Now lots of people make reports.” Mary said, “You know, I didn’t know that,” then she asked the young woman if she wanted coffee. Even through her discomfort, Mary was radiant as always. The young woman declined the coffee, but helped herself to a wafer cookie. Then she said, “You know it’s not like in the books.” And Mary, ever somehow both awkward and graceful, said “What? What isn’t like in the books?” And the bookish young woman said, “Being abducted.” She said, “There isn’t a bright beam of light, and they don’t tie you down.” Mary was just listening at this point, not knowing how to respond. The bookish young woman said, “But they test you. That’s why they take you away from your home, from your bed, so they can test the way things feel.” And here, Mary felt something sad turning over inside herself, and reached out to touch the bookish young woman’s knee, which only caused the woman to flinch. Mary backed off and listened as the girl finished her story. The girl said, “That’s why they take you. They want to know how you feel, to know if you are dangerous or weak.” The girl’s use of second person made Mary uncomfortable. The girl continued, “They want to know if humans are friendly. Then when they’re done, when they’ve seen how you feel things, they put you back where you were, on a street or in your bed.” Mary felt like crying, but she didn’t know why, and she felt like saying something, but she didn’t know what to say, so she said, “Oh, I’ve forgotten I need to pick a friend up from work.” Mary left without taking the tray with the coffee and wafers, still untouched save for the single wafer taken by the bookish young woman, and said, “Stop by any time,” as she saw herself out of the woman’s apartment, then out of the building to her car so she could drive aimlessly around Minneapolis for just long enough to seem like she might have actually been picking up a friend from work.

Mary likes to avoid her downstairs neighbors for different reasons. Living in the house’s main floor, in the apartment that Phyllis, and Lars, and Bess used to inhabit, are three young men who keep odd hours and work odd jobs and listen to odd, loud music late into the night. Mary Richards hates that she hides from her neighbors. Ten years ago, when she was still working at WJM, she would have gone downstairs and, not given them a piece of her mind, exactly, but gently asked them to be quiet, to be mindful of their neighbors, and they would have listened because she was Mary Richards, and people liked Mary Richards, and they did what Mary Richards asked. These boys, though, the one and only time Mary knocked on their door to ask them to be quiet, did not like Mary Richards.

The night Mary met the young men who live beneath her, she was, of course, asking them to be quiet because they were listening to music like buzz saws at ten o’clock at night. Ten o’clock! Mary was beside herself, so she knocked on her downstairs neighbors’ door, and was greeted by a man of average height and weight with short hair and a mustache that curled up at the ends. At first, Mary had to struggle not to laugh because she hadn’t seen a man, and a young man nonetheless, wearing a mustache like that since she was a little girl. She tried to ask the man to turn down the music, but the music was still so loud that he couldn’t hear her, so she stepped into the apartment, and shouted, “Can you turn that down?” while covering an ear with one hand and pointing down at the ground with the other. This was enough for the man with the mustache to understand what was happening, so he walked across the room and turned down the stereo. As he navigated the mess of empty bottles, discarded clothing, and piles of books, Mary scanned the apartment, spotted a long-haired man, seemingly asleep on the couch and a third, relatively clean cut young man sitting on the floor, cross-legged, holding a book open on his lap. How these young men could be sleeping and reading through the racket was beyond Mary. Mary also saw, on the far wall, just to the left of the stereo, a poster that read, “We feed the rats to the cats and the cats to the rats,” in large, block letters. There were smaller words beneath. Once the music was down, Mary asked, “What’s the last line of the poster say?” The man with the mustache looked up at Mary, seemingly confused. He looked around. Mary pointed at the poster, said “What’s the small print say?” The man with the mustache said, “And get the cat skins for nothing.” Mary didn’t understand for a moment, then the implications of the words slowly untangled and began to make sense. Mary said, “That’s,” she paused, then, smiling, continued, “nice.” Then she said, “Can you guys keep it down.” Her voice was high, waivered a bit. She went on: “I have to be up early for my job, and I can’t even begin to think about sleep with all this racket down here.” The man with the mustache said, “You don’t have to go to your job.” Mary said, “I have to go to my job.” The man with the mustache said, “It’s just a job.” And Mary, losing her temper, which she rarely ever does, said, “When you’re older and have a real job, you’ll understand.” Before Mary could leave, the man with the mustache said, “I could never be like you,” and Mary had nothing to say, she just stared right in his eyes. She wasn’t sure what she saw there, but whatever it was it was not what she expected—she didn’t see a lazy burnout, but something intangible and wise, gruesome and beautiful at once, a raw depth of emotion and disappointment and anger and grief. Mary said, “No, I don’t suppose you could be.”

When Mary left her neighbors’ apartment, instead of returning to her own, she walked out of the building, and onto the lawn. She looked up at the sky and felt a tightness in her chest. It wasn’t a heart attack, Mary knew that, but she wasn’t quite sure what it was. Her breath shortened and she thought that maybe she was having a panic attack. Mary wondered why she would be having a panic attack now, for the first time, and that’s when she looked up at the roof of her building and saw the girl from the upstairs apartment sitting in a lawn chair, looking up at the sky. Mary wondered if anyone or anything was looking back at the girl, and then her chest relaxed, and her breathing slowed. Right then, she knew that the man with the mustache was right—these people would never be like her, and they shouldn’t be. They were something new, Mary thought, a new day rising, a new type of person. New to Mary, anyway.

As much as Mary hates to admit it, this newness scares her. She doesn’t know what these people are or why they are the ways they are, and knowing these people makes Mary’s Minneapolis feel a little bit darker, and a little bit sadder. So now, most nights, when Mary gets home from work, she keeps the lights and television volume low and walks softly across her floor even when the girl upstairs is on the roof, even when the boys downstairs play their music loud, even when she feels so out of step in this strange new world surrounding her that she wonders if anyone would notice her at all.

—James Brubaker