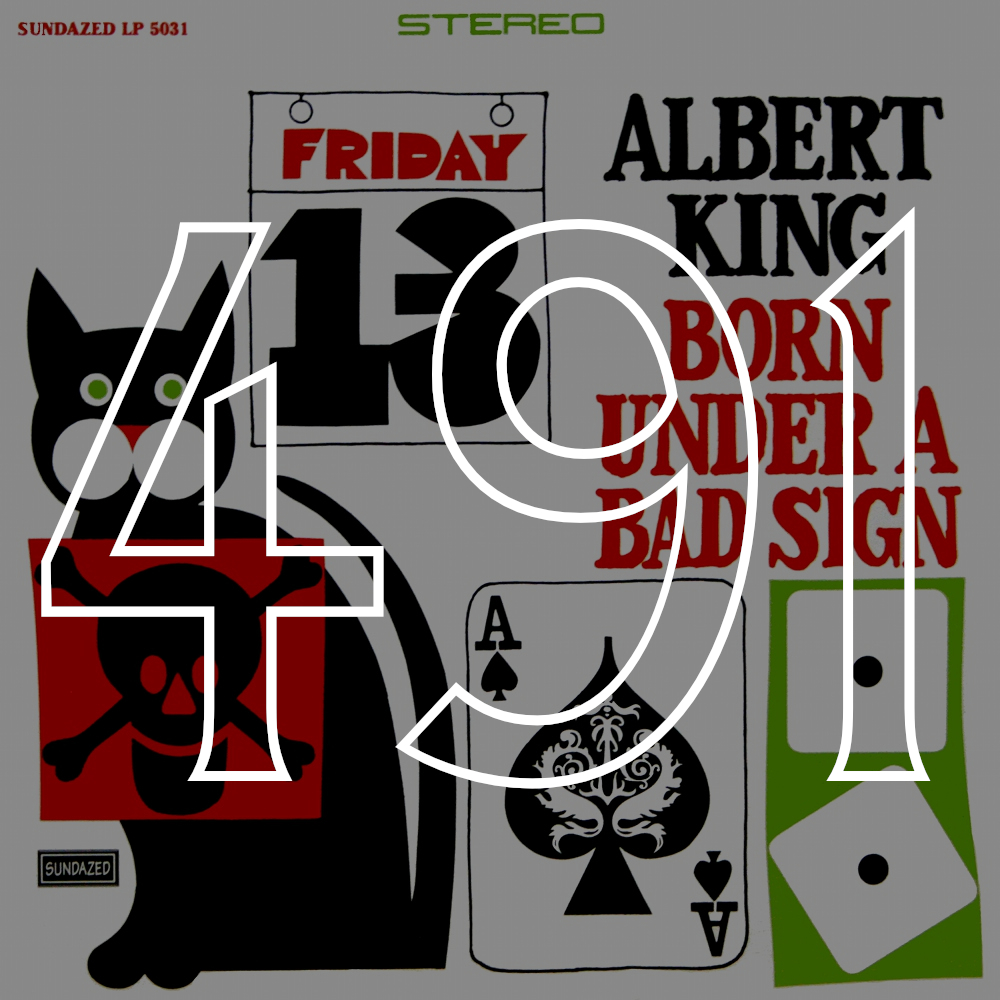

#491: Albert King, "Born Under a Bad Sign" (1969)

On our second bird walk around the neighborhood, Nancy crouched down on the sidewalk, flapping her arms to keep me from stepping on the feather, and shushed me like she was shushing a grenade. To a ten-year-old, her intent was clear: talk and you lose your throat. I kept quiet, but inched closer. Nancy picked up the feather and held it under her nose, moved it in front of her eyes, then settled it next to her ear.

“Sometimes you can hear the squawk,” she said.

I put my ear beside hers and heard a medley of birdsong, but like most everything else, it was only in my head. I held out my palm, hoping Nancy would let the feather float down. It was long and jet black with gray, leopard-like spots and looked softer than silk.

But Nancy hesitated. I was new to the neighborhood and a pretty ratty-looking kid, and how was she supposed to know if I was trustworthy? Nancy loved three dead things more than she loved anything living: John F. Kennedy, feathers of all kinds, and Albert King. Trouble was, she didn’t love them very much, either. Most days, Nancy referred to Albert as the husband she’d have chosen for her dearest, most annoying friend—someone she loved to see in small doses. Albert seemed like a guy you’d need space from. On her softer days, when her hands ached, she called him “Velvet B.” There wasn’t a walk that went by without Nancy humming a tune from Born Under a Bad Sign, which she believed was the only record of Albert’s worth listening to. “The other ones are twice as long, half as good, and three times as fat,” she told me once. But this was after she told me she was a feather finder. She always led with that, as though finding feathers was the part of her that mattered.

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

Because she didn’t like inviting people in, I only saw Nancy’s feather collection once, a few weeks before I turned thirteen. I thought it was a good sign that something lucky was happening to me before I was about to enter my unluckiest year. Nancy asked me inside, and then took me to her bedroom to stand in front of the nightstand and the shiny box carved from a cherry tree. I could see the moon-shaped reflection of the lamp in the wood. Nancy told me to open it, but I was afraid. What if it were a music box stuck on the blues, and, when I smoothed my hands on the box’s sides, Albert would ascend, granting desperate wishes I never should have wished? Or maybe, the box belonged to Pandora herself, full of every bad thing that ached to get out.

Of course, it was neither. It was a box full of feathers stacked on feathers, arranged from largest to smallest. Some of them smelled bad, and I said so. Nancy said, “Dead don’t go far.”

She was fond of speaking that way, in short pragmatic sentences. I hardly ever heard her expound on anything, and, in general, she wasn’t keen on words. I think that was partially why she loved Velvet B. Nancy didn’t sing many of Albert’s words aloud. “The blues don’t need words,” she said when asked. But I disagreed. I thought the lyrics made the song, and on bird walks I sung nonsense words along to Nancy’s melodies, which often earned me a soft knock on the noggin, her way of inquiring whether or not there was anything in there.

After enough pestering, she let me look at the album cover of Born Under a Bad Sign. I dissected the truly bizarre hodgepodge of a black cat, skull and cross bones, snake eyes, a Friday the 13th calendar page, and an ace of spades on the front, and then I moved on to the lyrics. I didn’t understand how these words fit with the songs I knew, and unlike usual, I was being too literal, asking questions like, What’s in Kansas City? Will I need a personal manager when I become a woman? Who goes on dates at the Laundromat? What kind of gun is a love gun? Nancy didn’t have answers for any of them; she just stated emphatically that I was missing the point. Albert didn’t write those lyrics anyway, and I would do well to turn my attention to the guitar, his fingers on the strings, the riffs and sounds that would shape guitar gods for generations to come.

*

Shortly after I turned thirteen, I left my house one night at dusk to walk off a stomachache. I took the back way to the park, through the gravel alley where I liked to knuckle-thump trashcans and bowl with acorns and squirrels. Circling back around just as the sun disappeared behind the hills, I hopped the fence to my backyard and climbed the rope ladder up to my tree house.

I heard the flapping before I saw the hawk. Trapped inside, it must have flown in the window that had since blown shut. The hawk was red-tailed and his left wing was broken, the bone jutting out into the air. When he tried to fly away as I approached, his body only scooted against the floor. I knelt beside him and looked him right in the eyes, the way you’d look at someone to show you empathized. His talons were curled in and tense from hours of trying and failing.

What is it like to lose your ability to move? To move is to be alive. I imagined my legs falling off and dragging myself across a splintery wooden floor toward a doorknob too high for me to reach.

The hawk crowed. I scanned the tree house and, as soon as I saw it, went for the baseball bat in the corner. I wrapped my fists around the barrel and swung at the hawk until the squawking stopped and the feathers flew. Red, gray, brown and white, tail, flume, bristle and downy, they floated and landed all around the interior of the tree house. I sat, cross-legged, and folded my hands in my lap. I pictured Nancy in her recliner, Albert on the record player, born under a bad sign, toothy licks, gritty and buttery at the same time, D to A to G. I stayed there for hours as the night went black, humming to myself, waiting to be found.

*

Years later, after Nancy had passed, I discovered that scientists have studied which astrological signs are associated with negative human traits. One such study on hospital admissions showed that Aries are more likely to enter the hospital but Pisces are more likely to stay. It was fascinating, and I wanted more. Don’t we all want nature to explain why some of us are lucky, some of us criminal, hurting ourselves and others, some of us so, so blue?

The data isn’t there. At least not yet. I keep going back to the signs, to the knotty horns and the slimy gills. I read the horoscopes and measure how far the moon has traveled from the oak tree in my yard. I have to be honest: the ram and the fish do nothing for me. Their mystery feels too small. And the rest of the signs feel limited, too, as far as explanations go. The virgin and the scales, the bull and the goat and the ugly crab, all so easily lost. The centaur gets close, but then even it is not able to fly. I am looking for a different sign, one that leaves behind tangible things which you can find on the ground or, if you’re lucky, sit among quietly and wait.

—Lacy Barker