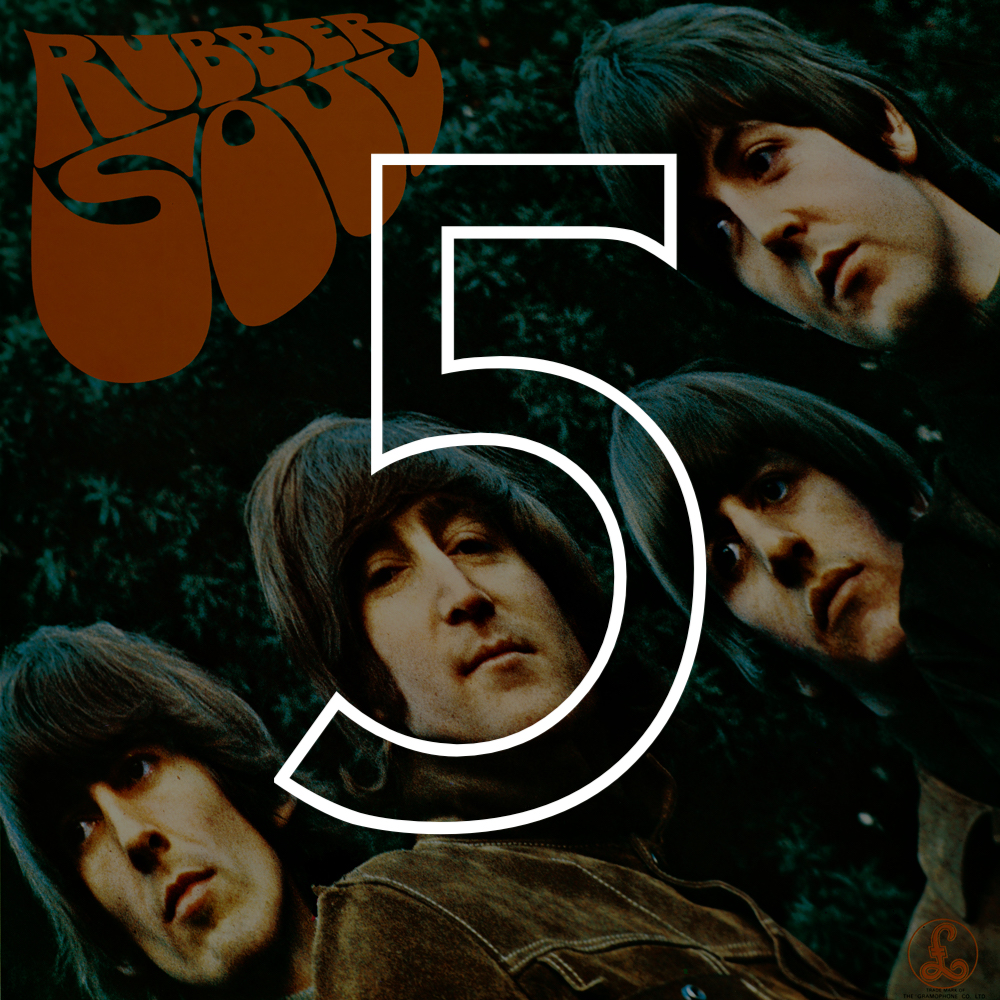

#5: The Beatles, "Rubber Soul" (1965)

It is summer 2019 as I write this. Over fifty years have passed since the Beatles’ final public performance, the legendary Rooftop Concert, and nearly as much time has elapsed since their final albums, Abbey Road and Let It Be, were released. John and George have been dead for decades. In that time, nearly countless books and documentaries and think pieces have sprung up around the shadow of the Beatles, including Julia Taymor’s film centered around the culture enlivened by the band, Across the Universe. All of these are attempts to keep their legacy fresh and impactful, their music and the discourse surrounding it in the spotlight. Innumerable products are named after Beatles songs, and satiristic takes on them still pervade media of all stripes. Many of these are accessible even to those who have never really listened to the Beatles. The Beatles, it seems, exist on a level wherein you don’t need to listen to them to get them. They just...are. The general consensus is often that the Beatles were the greatest band to ever exist, and thereby any discussion of that fact has fallen to the wayside in favor of considering the results of that supposed fact. After all of this, it seems that the only thing left to say about the Beatles is that everything has already been said about the Beatles. Unless, of course, you’re Danny Boyle and Richard Curtis.

Whereas Taymor imagined a world almost hyper-saturated with the Beatles to signify their importance, the pair appears to agree with the popular notion that the Beatles were the greatest band to ever exist, and then some. They believe this so strongly that their recently released film, Yesterday, wants us to believe that should the Beatles’ entire discography be erased from human memory and subsequently re-released in the late 2010s by a different performer, the songs would still rocket to the top of the charts, sell out arenas, save a desperate singer-songwriter from obscurity and have him team up with the still immensely successful Ed Sheeran. There are so many holes in this argument that I still have trouble understanding how the screenplay made it to popular release. To start, if the Beatles were so instrumental to the development of rock music we have today, how could Ed Sheeran of all artists exist in a universe without them? I find it hard to believe that we’d have “The A Team” without “Happiness is a Warm Gun,” or the multitude of songs penned by white men in the decades between them. The film’s premise rests, I assume, on the line of thought that the Beatles’ music is timeless in that it transcends time and generational tastemaking (as seen in the scene when the main character is asked to change “hey Jude” to “hey dude”), but that argument doesn’t sit well with me. Nothing exists in a vacuum, and context matters. Even if the Beatles themselves were born to be the same age as the protagonist, the Beatles that would have formed would not have been the Beatles we so desperately laud and mythologize. It is absolutely bizarre to argue that something means so much it ultimately means nothing at all.

Yet, despite its logical fallacies, the film has garnered $80.5 million at the box office just three weeks after its release, and as going to the movies is too expensive just to hate-watch something, there is obviously a vested interest in the film somewhere. Perhaps the bulk of viewers are fans of either Curtis’s and Boyle’s past films, or perhaps they are Beatles loyalists intrigued by what the world would look like without the music they have so adored over the ages. Maybe, more likely, they are casual viewers looking for a fun summer flick and a chance to hear a few catchy Beatles tunes, searching for another Beatles memory to add to their personal catalogue.

This, I think, is what bothers me so much about the concept of Yesterday (and indeed much of the discourse around the Beatles). In the pursuit of the Beatles’ Big Legacy, we lose sight of why music matters in the first place. None of the artistic innovation credited to the Beatles would matter if there weren’t rabid audiences waiting to hear them. The British Invasion would be pointless if it didn’t fulfill the dreams of thousands of teenage girls’ greatest wishes, and their prolific discography would seem like fluff if there wasn’t a generation which seemingly created a culture around and moved into adulthood in tandem with it. Music matters because it means something to people, and the Beatles mattered because their music meant something to a whole lot of people at precisely the right time.

*

My memories of the Beatles are mostly memories of wanting to have a connection to the Beatles. I had a yellow cardboard replica of the Help! movie poster hanging in my childhood bedroom for almost ten years, but I’d never seen the film (I still haven’t). I bought it at one of those kitschy music curio shops, the sort of place brimming with Jimi Hendrix flags and Bob Marley grinders and, yes, Beatles memorabilia to excess. I was thirteen or fourteen, and I was very desperately trying to mold myself into a person I wanted to be. I had music I loved desperately—mostly pop punk a la Fall Out Boy and Panic! At The Disco and indie bands like the Format and Death Cab for Cutie—but only a small sliver of that aligned with the tastes of the type of person I wanted people to think I was. I was a pretentious pre-teen; I wanted to be a writer who wore cardigans and used a typewriter and drank black coffee and strolled through autumnal quads, the type of person who played classic rock LPs on a record player and who surely had strong opinions on the Beatles. I probably spent three dollars on that poster in an attempt to be the person I thought I wanted to be under the assumption that the signifier of knowledge would suffice. I also spent countless hours watching and re-watching Across the Universe, a film I genuinely love, whose theatrical take on the Beatles catalog resonated well with my high-school-theater-kid self. I came to love several songs from the film, for their musical value, yes, but more for what they gave in terms of storytelling and character building: “I Want to Hold Your Hand” was not just a song of longing, but a song of repressed sexuality and desperation amidst a daydream; “Strawberry Fields Forever” is a track about drugs, but also about artistic stasis and literal war, and the magnificent gospel take on “Let it Be” underscores a scene about the suffering and struggle of black Americans. The movie takes the Beatles’ grand cultural history and shrinks it down to personal narratives. It showed me why this music mattered so much to so many.

I’ve since given up pretending to like things to which I am ambivalent, and therefore have not listened to the Beatles much this side of twenty beyond requisite streams of “Dear Prudence” on particularly nice spring days. The only Beatles tracks I remember having any vested interest in are those on the white album, and even then, I was more interested in the project as a concept than the actual songs it birthed. While working on this, I realized that I could only even name three songs off of Rubber Soul: “In My Life,” which I didn’t know was on Rubber Soul, “Girl,” with which I was mostly acquainted through the phenomenal opening rendition in Across the Universe, and “Norweigian Wood,” which I’d never actually heard. I went into the album fresh, a 26 year old fifty years removed from Beatlemania, an experience akin to one of the characters in Yesterday.

It is, of course, impossible to completely decontextualize the music from the Beatles’ history; for instance, it is quite literally painful to listen to a song as gleefully misogynistic as album closer “Run For Your Life” while knowing that John Lennon was a violent domestic abuser. In similar stride, many of the tropes throughout the album are dated and stale, love songs indistinguishable from the rest of the mid-60s rock scene. This is something the Beatles themselves acknowledged; legend has it that the album name is a reference to their appropriated—or “rubber”—take on the Black soul and rock upon which they built their style and which catapulted them to stardom, an anecdote I cannot forget while listening to the album.

I do not think that the Beatles are the greatest band of all time—I don’t have an alternate suggestion, but rather, I think the idea of naming any one band as such to be archaic and limiting. I do not think that the Beatles would have been superstars if they—or someone performing their songs—came on the scene in 2018. This is not to say that the Rubber Soul didn’t strike any chords for me.

I recently tweeted, half-jokingly, that “Olivia” by One Direction was my favorite Beatles song, all string sections and horns and singalong pastoral choruses, but it’s true—the Beatles songs that have always stuck out to me are the ones that move with a grandiosity, with a light, something into which you can willingly dive, then float. I listened to Rubber Soul first on one of the muggiest days of the summer, in the midst of a mental health period I will generously call “unpleasant.” I was doing research while listening to Rubber Soul but, on some level, I knew I was doing what I always do with music, which is to find some form of escape from whatever happens to be plaguing me. I was looking for something summery, light, something eons away from the anxiety consuming me, not unlike the One Direction song, or any number of Coldplay tunes, or something from Ed Sheeran’s more recent albums. I heard most of Rubber Soul on autopilot, the tracks blending together (something I learned was the Beatles experimenting with a more continuous, less singles-based album structure), until I came to “I’m Looking Through You.” It was poppy and jammy, the guitar memorable and fast. It was the kind of track you imagine blasting on a car ride, shimmying your shoulders, screaming when thinking about someone you have outgrown (maybe yourself). I listened to it no less than ten more times in a row, clicking with it in a way I haven’t with a song in a long time. I forgot it was Beatles song™️, forgot it was a song I needed to write about, forgot its role on the album or as a part of the Beatles’ grand musical legacy. It was simply a very good song, timeless in its appeal, that found me at the perfect moment.

—Moira McAvoy