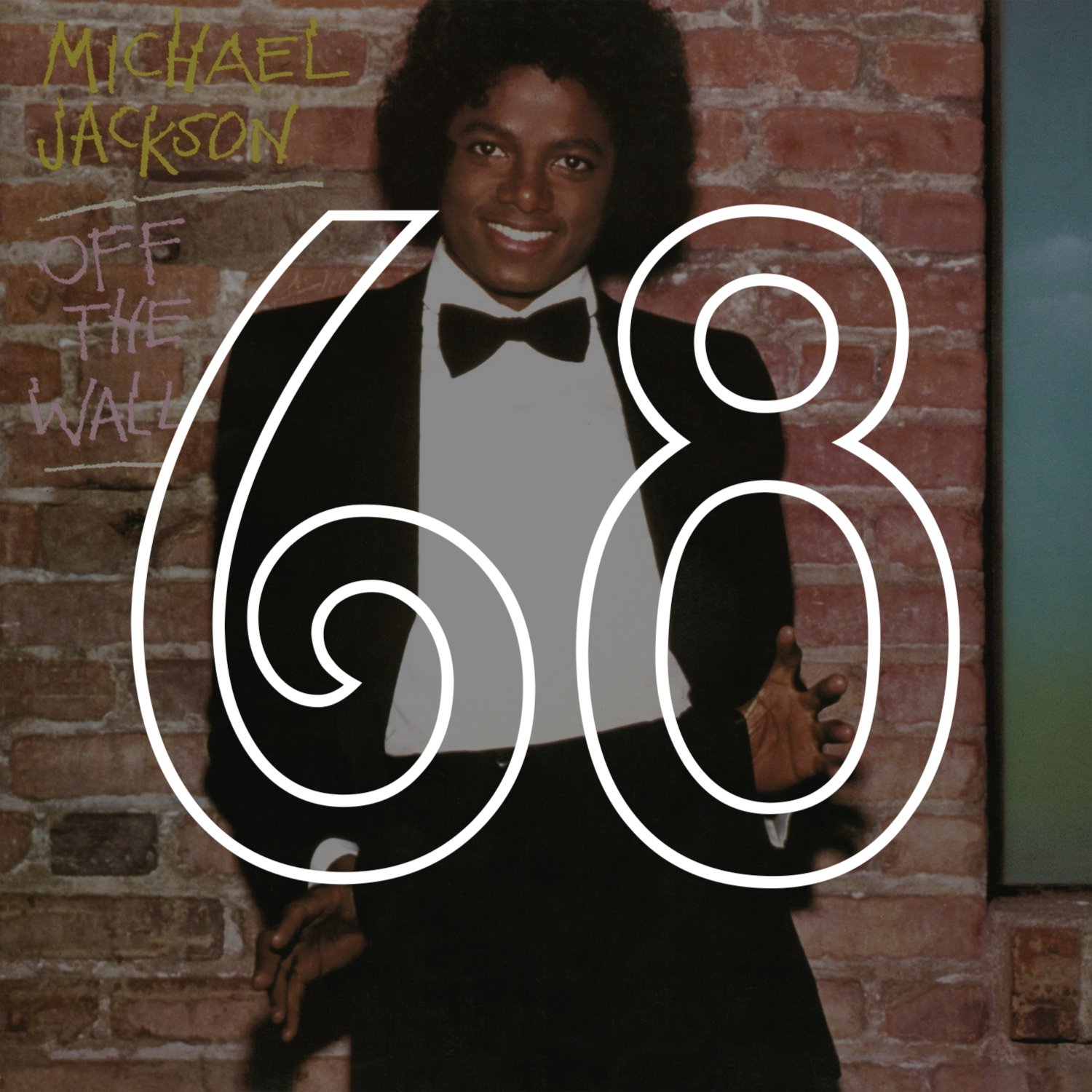

#68: Michael Jackson, "Off the Wall" (1979)

My first memory of Off the Wall comes from 1984, when the album was 5 years old and I was 6. My parents had split up much earlier; in fact, they divorced the very month Off the Wall was released. By 1984, my mom had married a man whose teenage son (my idol) stayed with us a few nights each month and he coached me on what big kids listened to—Thriller, in a word. That summer, I flew to see my dad, who’d moved out of state with his new wife to a kid-free home with fancy crockery, hi-def electronics, and—much to my delight—a big record collection.

Upon arriving at Dad’s house, I announced to my stepmom that Michael Jackson was one of my two new stepbrothers. This seemed to me very possible, given the amount of people I adored who lived other places, with other families. She and Dad had filed their records in an oak cabinet by the den. I asked her to “play Michael Jackson,” which, to my six-year-old mind, meant playing Thriller. “We do have one of his albums,” my stepmom said, “but it’s an older one,” and then she pulled out a cover with a smiling young man who looked the age of my babysitters. He wore a prom tuxedo and leaned against a stack of bricks. Sans glove, sans glitter. I didn’t recognize his face.

She attached a gigantic set of headphones to the receiver and started the album. The headphone cushions were so big they squished my cheeks in, but through them, I first heard the strained whispers and swarm of disco violins that kick off “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough.”

There are no violins on Thriller, I thought. What the heck was this?

Who knows how far beyond those opening measures I got before abandoning the stereo to find something else to do. But for years, Off the Wall was, to me, another disappointing knock-off of My Amazing New Brother. It reminded me of the countless MJ send-ups on Saturday morning cartoons—a moonwalking Smurf or a Chipmunk squealing through “Beat It.”

Three decades later, that exact copy of Off the Wall is here next to me while I type this, still in fabulous shape, perhaps because it was so rarely played until I recently snatched it from Dad. If you haven’t heard an analog copy of Quincy Jones’s masterful production, woven like the late-disco equivalent of a Flemish tapestry, you’re missing out. It may have taken me decades to realize its power, but Off the Wall now rates as my favorite headphones album in all of Pop.

Where Jones and Jackson designed Thriller to be a record with as many hits as (super)humanly possible, this first collaboration smacks more of a unified sonic concept. You can hear in the production a pushing back against the flaccid, uninspired disco that, post-Saturday Night Fever, had saturated basic American culture. Of course, much of Off the Wall is still very much in the spirit of disco—jaunty bass-lines, orchestration that shimmers like a mirrorball, and an alarming number of lyrics discussing “the boogie”—as in THE boogie with a definite article, thank you very much. But in addition to these disco markers, the Off the Wall sound is always complex and polyvocal, lush and anti-metronomic. It breathes and moves as it blends funk riffs, Latin rhythms, Quiet Storm balladry and contrapuntal jazz runs into a barreling, gleeful menagerie of the best that ‘70s dance music had to offer, both including disco and moving beyond it.

Even though Off the Wall is chock full of singles (the first four released tracks all charted in the Pop Top Ten), it enjoys the kind of cohesiveness that’s cherished in capital-A albums like Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely or What’s Going On. The album is exceptional, I think, because it designs this irresistible unique sonic language for itself, and then, over the course of nine songs, it teaches the listener to hear—and revel in—that language.

The two dozen session musicians—Louis Jordan, Wah Wah Watson, and the splendiferous Sea Wind Horns among them—play Jones’s dense arrangements with a sparkling sonic profile that establishes, then maintains, and finally challenges itself by the close of the second side. Over the course of nine tracks, this unique sound becomes not only familiar, but familial. And there, at the head of this family table, is Michael Jackson’s singular voice.

This is his first solo album away from all his other families; both Motown records and his brothers are absent (save Randy, who plays hand percussion on “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough”). And from the first note he sings, Jackson tells his new family, they of the Quincy Jones studio, that he has come to play. Listening to him, I get the impression of a precocious kid at a big Thanksgiving meet-up, running from kitchen to living room to card table. Bright and engaging, he joins in on any conversation that will have him, talking big game, stirring pots, parroting punch lines, and yelling at the football on TV. With each visit to some family clique, he spazzes out even more, but that kind of energy is never anything but welcome, especially when it comes packaged in a voice like his.

The first note he hits—that OOOH! at the start of “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough”—is the highest vocal moment of Off the Wall. Right out of the gate! That bent shout, just shy of a soprano’s high C, opens into the melody line, where MJ lives in the fifth octave, soaring over the measures in a breathy falsetto not unlike the lofty string hits at the top of the track. MJ vox as disco violin? Check.

Not to mention, “Don’t Stop” is of his own devising, one of the three songs he wrote for Off the Wall, all of which appear on Side A. Visceral and alive, MJ sings of a “force” that has brought him into this sonic space, one powerful enough to keep him pushing, keeping on, until his appetite—for love, for music, for kinship—is sated.

On the next track, “Rock With You,” Jackson’s voice drops a full octave, refusing falsetto for all but a handful of measures. His singing is less overcome here, more wry and confident, as one must be when asking one’s partner to take this dance to the next level. And while still managing to be smooth as hell, MJ’s “Rock With You” vox sports a terrific chestiness, with a kind of push in the highest notes of his melody that sounds to me like a Sea Wind horn in mid-bleat. MJ vox as sexy sax, as “magic that must be love”? Check and check.

And don’t even get me started on track three, “Working Day and Night,” which launches MJ back up into his falsetto, but also builds on that established sound with a second vocal challenge. Jackson’s breath, grunts, and sighs all groove alongside the heavy arrangement of hand percussion—bottles, handbells, and claps—that runs through the song. MJ vox as hot drum track? Chicka-chicka-uh-uh-check.

I defy you to find a more cohesive Side A in pop music—the gradual architecture of instruments (MJ included), the shifts in tempo and tone, and the delicious volley between fervor and disco glide. It’s perfectly parsed to tease the listening body (as well as the dancing one) up and back and up again: You don’t stop, and then you lie back and rock with somebody. You work day and night, then you get on the floor and dance it away.

Side A culminates in the album’s title track, in which Jackson’s voice daps that high B-flat from “Don’t Stop” with the lowest sung note in the album—a C# nearly three octaves down-key from where he began. In his “Off the Wall” vocal, we hear all the earlier tricks so far—percussive grunt, soaring falsetto, gritty belt—working together, plus the added treat of the backup vocals: several pitch-perfect MJs multi-tracked into a tight funk chord. MJ vox as decathlete, as fifth element, as a Jackson 5 choir all to himself? Quintuple check.

Side B is both more easygoing and more expansive—a goofy Paul McCartney pop cover, a weepy ballad, and a duet all painting with the same palate from Side A, but flying further from the bar each time. It kills me whenever I hear the first notes of “I Can’t Help It”—the Stevie Wonder and Susaye Green song that, according to Spike Lee’s 2016 Off the Wall documentary, Jones plucked from the slush pile of Songs in the Key of Life. I’m just crazy about this song—the Wonderful key changes alone! It carries all the out-the-gate thrills of a track one or track two, but lives tucked away at the back of Off the Wall, waiting in the third-to-last spot like a sneak attack.

In it, you hear the jazzy, smiling voice that Michael brings to Thriller’s “Human Nature” and Bad’s “I Just Can’t Stop Loving You,” but this vocal take sounds more in apprenticeship to Jones and Wonder’s original work-ups. Though he was already one of the most famous voices on the planet, in 1979, Michael Jackson was still audibly capable of showing us the way a song might surprise him—how he might meet its challenges with reverence, delight, or almost prayer. That surprise, in turn, almost always surprises me when I listen to it carefully.

For me, the payoff of deeply considering pop culture is the rare chance to feel the scales of hype drop away from an icon. Sometimes, if you deeply listen (or re-listen) to a voice that’s been thrown at you your whole life, and you do so with both innocence and abandon, the icon attached to that voice is denuded of all the superlatives that the world decided to heap upon it—superlatives that often talk over an artist’s purest talents. Perfect expression never needs fame to do its job.

Stripping fame away to view such expression on its own terms often brings the voice closer to me as a listener, with no decades of overblown storytelling, mass marketing, or laden criticism between the two of us. When it’s just the voice and its audience, there’s a different sort of kinship at work, a magic that must be love. You might go so far as to say that it is, in its way, a kind of family.

—Elena Passarello