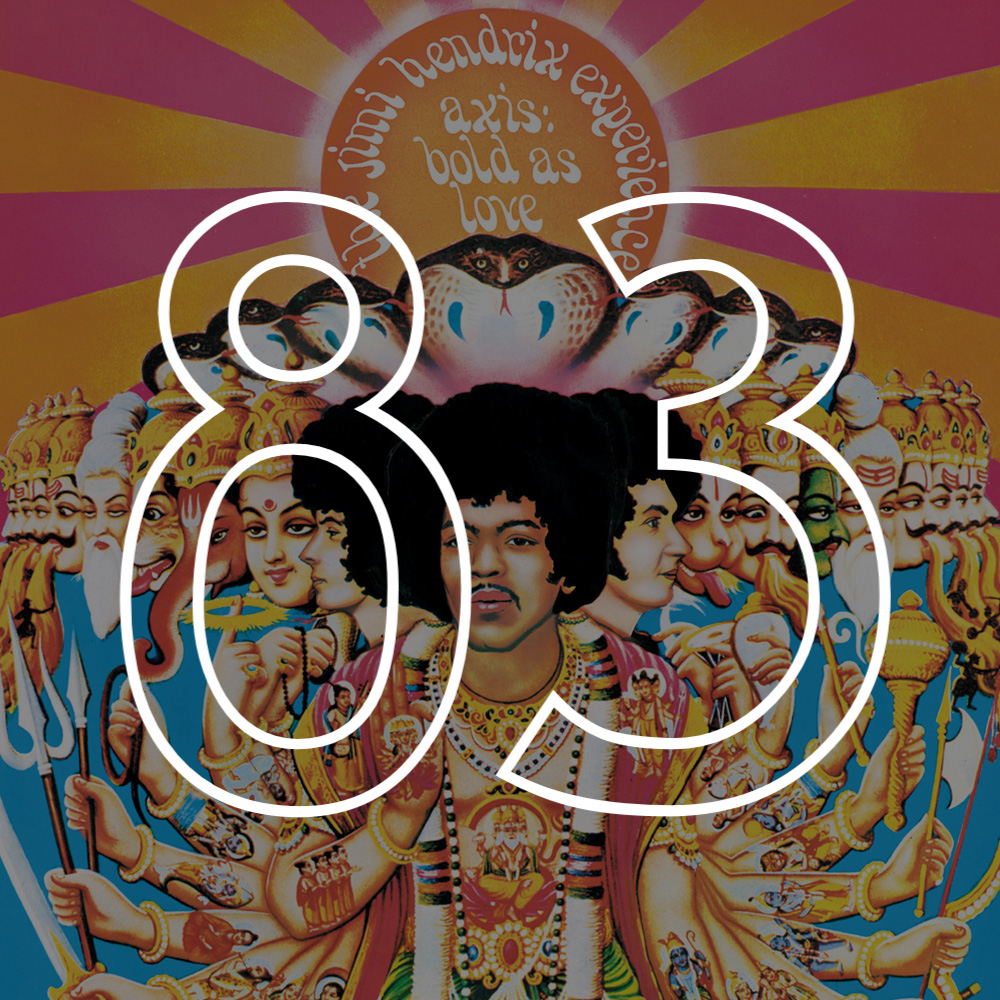

#83: The Jimi Hendrix Experience, "Axis: Bold as Love" (1967)

It was early spring. My husband was away for the evening, and I had the apartment to myself. I was restless and stir crazy and riddled with a sort of itch that indicated a quiet Friday on the couch with my laptop wouldn’t quite cut it—and the only hope I had to outpace this feeling was by getting in my car. It was light when I left the house, but already deep dusk by the time I reached the edge of town. Despite the early evening dark, it was warm enough for the tang of the neighboring cow pasture to have started to thaw into the air: the first and truest sign of Spring, even with the blackened crust of ice still hemming the roadway. I followed a one-lane state route under a glowing moon, squirming in the driver’s seat. I should be working: it was like an accidental motto I’d adopted. There were always papers to grade, manuscripts to edit, rooms to tidy, muscles to tone—if it couldn’t be lauded as productive, it shouldn’t deserve my time.

I winced with every pair of headlights from oncoming cars. They were painfully bright, but also irritated me, the presence of others as I was trying to drive my way to isolation, someplace where it was just my thoughts and a simmering inexplicable urgency I assumed hurling myself into would help quell.

Capturing what this drive feels like and the need for it is hard. And for two reasons:

The older I become, the more difficult it is to acknowledge and process my emotions. I feel an uneasiness around even the most benign of them. This is bad news for a writer.

Some feelings do not lend themselves well to being portrayed in language altogether. At the end of the day, feelings are abstract, no matter how many sensory details we try to staple to them. This, unfortunately, is also bad news for a writer—along with probably everyone else who wants to meaningfully express themselves.

The pastures adjacent to both sides of the road are serene and mostly empty; they host a few trees, green-black in the darkness, that cast diagonal shadows across the dash. The radio station that I’ve been ignoring begins to play something that catches my attention: an electric guitar that is golden and melodic, a glockenspiel sounding like a celestial bell, a shimmering warmth that is the audio equivalent of the wavy distortions of air above summer pavement. “Little Wing” is unmistakable, and slows my spinning brain to match its meditative quality. It is languid like watching honey poured into a spoon, and sounds almost like the sunlight color of it, too. There is a reason Hendrix’s music is often labeled psychedelic. How else do I talk about what it makes me feel: soothed by melody, energized by the drum fills, sad and wistful and relaxed all at once? Look at those empty adjectives: what a cop-out.

The only other way I know how to talk about what this album can make me feel is the time when I was 8 and also heard Hendrix on the radio: legs plastered to the scalding vinyl back seat of my mother’s ‘73 Plymouth Duster. The music made me feel like the emblem on the car’s quarter panel: a spinning cyclone with big wide open eyes, a still image conveyed in a blur of movement, a cloud of electrons that could peer out at the world with an eagerness to take it in. On the spot, I asked for a Jimi Hendrix album for Christmas, still almost half a year away.

I delighted in discovering that Hendrix and I were both left-handed. I watched a rented VHS of him at Monterey Pop—which, in June of 1967, was when Axis: Bold as Love was in the early stages of recording. I leaned in close to the TV screen, watching his guitar in flames, Hendrix kneeling as if at an altar, lifting his fingers into the air like he was trying to coax the fire up as tall as possible, exorcizing something unsayable from it. It mesmerized me. This may seem like a stretch, but I suddenly felt understood all the times I cropped my doll’s hair, or drew on Barbie’s face and rubbery limbs with pink pen, or even the pleasure I felt at tearing snack wrappers into strips before tossing them into the trash: a feeling that could only be expressed through action, impulse.

Hendrix in interview footage (at least the clips I’ve seen) is taciturn, evasive, offering a shy smile or a shrug after a sentence into the microphone. But I hear so much else when I listen to the muddy, almost aggressive guitar of “Spanish Castle Magic,” the near-flippancy at how cruel life can be in “Castles Made of Sand,” and can understand how he could have recorded three studio albums between 1967 and 1968: this is someone who has a lot to say, who is trying over and over to present it to us just right, even it it might remain obscured.

I wonder if he, too, felt a churn in his stomach to be productive, to do everything possible, to maximize a checklist. Probably not in the same way, but given his brief but prolific life, it seems Hendrix may have also felt an encroaching ennui he tried to outpace with the aid of his guitar. I think of him singing, “I wanna hear and see everything” over and over on “Up from the Skies,” and it serves as an important reminder to recalibrate to a more meaningful definition of “productive,” one that values my time—my life—beyond how many tasks I can finish by the end of the week.

Maybe I can start by rolling down these windows, the meadow-scented air tousling my hair into knots, turn the volume up until I feel the bass beating through the seatbelt across my chest, until my shoulders unclench and it’s only high beams and stars and shadows of telephone wires cast by the moon, propelling into darkness. I am feeling something real and sincere, and I want to share it with you, for you to believe me, but I don’t know for sure if I can tell you in a way that’s easy to understand.

—Lisa Mangini