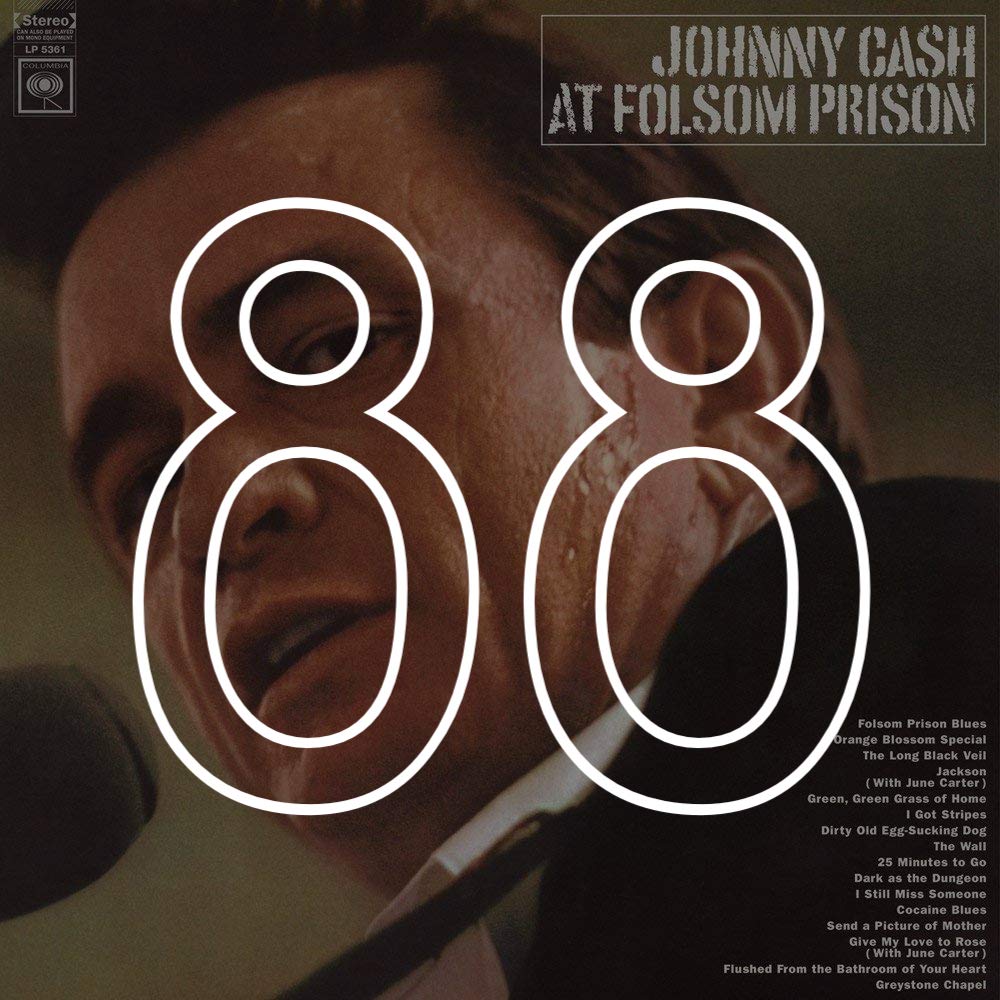

#88: Johnny Cash, "At Folsom Prison" (1968)

Johnny Cash died fifteen years ago last month. Fifteen years ago I was in high school and music videos were my window into the world outside Lunenburg County, Va. Some days, getting to the top 40 countdown on CMT got me through school, my hour-long bus ride home, and the dusty walk from the stop home. And when the Toby Keith worship in the aughts was too much on CMT, there was always GAC to switch to.

Something funny happened on both channels in 2003. Johnny Cash released his version of “Hurt” and it rose through the charts and was in heavy rotation on the video channels up to his death. The song wasn’t his own but like his many covers, he made it his. In the video, he sits alone, surrounded by relics of his life, and videos clips from his youth cut in. He’s still the man in black in the video, but he’s Johnny without a June by that point, and his piano resembles a coffin’s ledge.

Cash was able to channel someone’s hurt and feel it as his own. But, he always could.

“Hurt” became so much his own that my friend and coworker Shannon thought he wrote it. While stacking books at the shop we both work for, she told me how in the early ‘00s she got into an AOL chat room argument with a whole group of Nine Inch Nails fans.

But long before that—50 years ago—Johnny Cash really lived. He played two shows at Folsom State Prison on January 13, 1968. The first recording makes up the bulk of At Folsom Prison.

There’s a certain magic in that first show. He riles up the crowd of prisoners with “Folsom Prison Blues” and settles them back down with “Dark as a Dungeon.” “Hell, don’t you know it’s being recorded,” he asks them in the middle of the latter song.

His perfection is a little desperate, maybe because he was. Cash was at a turning point in his career in 1968. He needed a hit and in the lead up to these two performances, he rehearsed the set list for days.

There’s an anxious energy to the album that could have only been captured at that point in America. 1968 was a restless year. Protesters were vocal. The album release preceded the killing of Robert F. Kennedy by just a month, which resulted in a cleaner cut of “Folsom Prison Blues” being released. In a time of stark divisions, Johnny Cash was the kind of man who could cross them.

It’s a lesson I’ve had a hard time internalizing, even though At Folsom Prison is on heavy rotation in my house. I have a problem with empathy. My mother calls it a problem with patience: the fact that I can’t sit still or care about the problems of people who I feel have had every advantage, and squandered it.

When my family runs into trouble (gets arrested, flunks out of school, gets locked up, ends up squatting with me) I have a hard time feeling much for them. If I could climb my way out of a situation through hard work, then surely so could they.

Maybe it’s misplaced pride. Perhaps I’m just a cold fish. But it’s hard to tell people close to me I understand, even though I’m a writer who pulls unlikable narrators out of thin air and cherishes them.

It’s easy to feel for the downtrodden, for the victims of weather, for those whose only crime was seeking a better life in a new country. But it’s hard to care for the discouraged, the ones who could turn a new leaf but are stuck on which direction to go.

It’s a heavy lesson and one that is reflected in the music. The opening riff of “Folsom Prison Blues” features eight laden chords. Merle Haggard did the same thing when he wanted his crowd to empathise with his narrator on “Mama Tried,” opening with a low, distinctive set of chords. Songs about jail start heavy, but they get lighter. They’re catchy. Cash so wants to reach out and reel us in.

But if every virtue is a vice, then the opposite is also true. Johnny Cash, a man of many vices, could empathize with the prisoners at Folsom like few others. He never did hard time, contrary to his lyrics, but he did spend a night or two drying out in local cells.

His career was in a downward spiral when he hit that stage. He had already reached fame years ago with “I Walk the Line” and “Ring of Fire”—both, notably, covers. He was climbing out of addiction and Columbia Records was wary of him. Columbia didn’t expect it to, but the album caught on. He won a Grammy. He sold a lot of records. Johnny Cash got the hit he needed all because he reached out to a group of people who were not used being cared about, because he could employ basic empathy.

Johnny Cash knew how to churn out albums; Folsom was his 27th. And he hatched the idea of playing in a prison years before. He wrote “Folsom Prison Blues” in 1955 after watching a documentary about the penitentiary.

He wrote the famous line “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die,” because it was the worst thing he could imagine someone doing. It’s devoid of compassion, but crafted in the spirit of it. And when he begins the song on At Folsom Prison, the crowd goes crazy for it, because it was written just for them, in anticipation of that moment.

Though it was his first live recorded prison performance, Cash played prisons before Folsom and he recorded more albums in them later. He went on to record At San Quentin in 1969, Pa Osteraker in 1973 and A Concert Behind Prison Walls in 1976. But none of those packs the same fire.

He ends the album with “Greystone Chapel,” another cover, which was written by Folsom inmate Glen Sherley. In an interview, Cash said he heard the song the night before the show and he stayed up all night to learn it. He needed to give Sherley justice. Cash’s own “Joe Bean” may be the better song about a convict on the record, but his insistence on hearing out the downtrodden makes his performance of “Greystone Chapel” so affecting.

Prison reform was Johnny Cash’s great cause, but Sherley was the face he gave the movement. Sherley’s story after prison doesn’t end well. It ends like a song Johnny Cash might have written himself.

But the contradictions in Cash’s own life make the record so beyond compare. The ultimate patriot, he could criticize his country. He was a backslider among backsliders who sang gospel that was deep and moving. He was a smooth operator whose pure love for June Carter made their story so sweet. At Folsom Prison is emotional in a way few albums are. Sincerity is something we take for granted, emerging in 2018 from the age of stubborn irony. It urges whoever’s listening to believe the addict as a gospel singer and the prison reform advocate as a patriot—and to understand that these identities are not mutually exclusive.

Johnny Cash would hit more hard times. His “Cocaine Blues” weren’t over. He’d be “Busted” again. And he’d climb out of it.

Here’s what Johnny Cash knew: We all build prisons for ourselves. I tend to imprison myself in work, in a shell of busy fervor. But I could take a page out of the book of the original non-role model and step out in all black, not just because it makes me look skinny but also because I should care about the dozens and hundreds and thousands of individual lives lived alongside mine, and say “Hello, I’m...”

—Lindley Estes