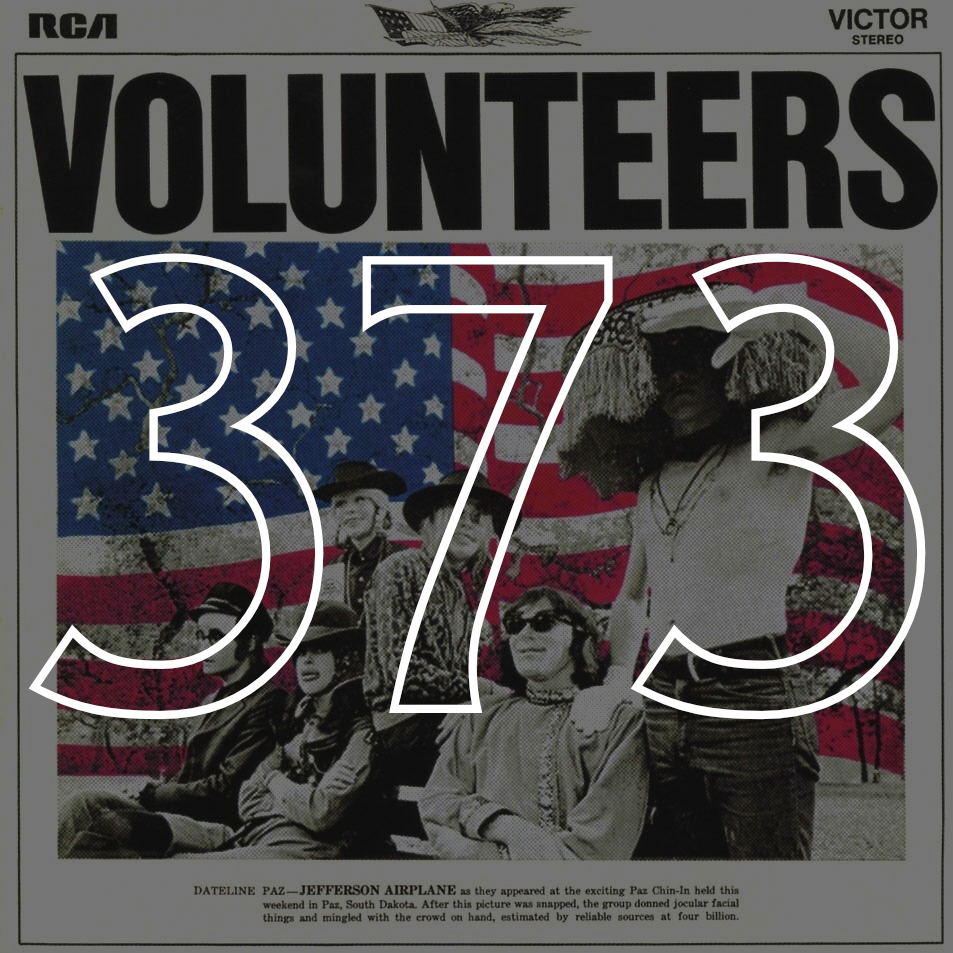

#373: Jefferson Airplane, "Volunteers" (1969)

When I was a little girl, I was a pacifist, though I used to punch my best friend on the playground when he swore. When I got older, and I saw how many people could not survive the long wait for peaceful reconciliation, I changed my mind. Today I cringe, remember the arrogance with which I declared to a room of friends, “I’d go to war, if the cause were just,” because I wanted to believe I would—I think it would feel good to be righteous, don’t you? It’s the ultimate Manichaeistic fantasy: If I’m good, and they’re evil, nothing I do against them could ever be wrong.

It feels cool, brave, and essentially American to speak this way. Yet the world is full of just causes, and I’m not going anywhere. On the other side of twenty-five, I find myself tossing in my sleep, eyes shut tight against the nightmares on the television screen while the chorus of “Volunteers” rages through my head:

Look what’s happening out in the streets

Got a revolution

Got to revolution

Hey, I’m dancing down the streets

Got a revolution

Got to revolution

Volunteers is a good album, Jefferson Airplane’s sixth, and the first I’ve reviewed for The RS 500 that actually warranted a place on Rolling Stone’s list. The tracks reel with woozy guitar riffs and the kind of folksy, melodic through-lines that make moonshine and skinny-dipping feel like natural epilogues to any Friday night soiree. The album has everything an essayist could ask for—a hidden swear word, a censored title, bed-hopping band members, and a passionate anti-patriotism that loves the people while despising their oppressors.

Released in 1969, and titled satirically after the faith-based nonprofit Volunteers of America (Jefferson Airplane was aiming for “Amerika,” but had to withdraw the name due to objections), the album exudes frustration with American politics in general and the Vietnam War in particular. Now, I’ve a limited enough understanding of present world events to know that keeping my mouth shut is almost always the better option, so I won’t attempt to take on the specific zeitgeist of the sixties and seventies, but will merely say that overtly partisan art makes me uneasy, especially when the message is so deliciously destructive as to border on hedonism.

“We are all outlaws in the eyes of America,” promises the album’s rabble-rousing opening track. “We are obscene, lawless, hideous, dangerous, dirty, violent, and young, but we should be together.” What a thing to say. Got a revolution, got to revolution.

But revolution is dangerous, and damaging, and plays, again and again, straight into the hands of whatever capitalist war machine taught us that paying our debts in human life is a perfectly acceptable transaction. I mean, wouldn’t Bitcoin be a better alternative?

There’s no way to live that does not place a burden on others, or deplete the larger system—if I write on vellum, I slaughter the beast; use paper, I kill the tree; but if I do not write, the story dies, and is not the story another life? (One that may outlive the herd and the forest.) But there’s a reason the angel guarding Eden carried a burning sword—one that cast light instead of darkness, knocking down shadows with cauterizing flame. It was a blade that healed as fast as it maimed.

The perfect revolutionary does not fear the destruction or death the act may cause. This person knows that a death of principle outweighs a life of cruelty. I admire these people greatly—priests and soldiers and countless, selfless others—a child may display this willingness just as plausibly as a grown man or woman—but I am not among them. I want to live.

So what recourse is left to those who ache for our world yet will not lie down for her? I propose to you, in all seriousness, that the answer is before us.

Volunteers.

Though Jefferson Airplane’s rhetoric was problematically simple, their personal expression of rebellion was spot fucking on. What Jefferson Airplane did to express their own frustrations was much more effective than what they urged others to do: Jefferson Airplane made music. And then they shared it.

Last month my friends and I saw Frnkiero and the Cellabration perform at a tiny venue in Hamden, CT. I’m not sure how The Space stumbled upon its perfect name, but at first glance that’s all the place really is—tucked away in a cramped industrial complex, the building announces itself by way of two neon palm trees, scattered picnic tables, and a quaint, free-standing ticket booth that squats in front like a Hobbit hut. It’s nothing like the chrome concert halls I learned to love in Baltimore, or the dive-bar karaoke I enjoyed tragicomically in Roanoke, VA. You know that gap in between what you think you want, and what you actually need? Yeah, that’s The Space.

You enter onto a landing at the base of a split staircase offering visitors a tantalizing choice: go upstairs, where wait a vintage clothes shop, 80s arcade hallway, and, rather pressingly in my case, the bathroom—or turn right and descend, entering a concert hall that looks a lot like your high school cafeteria, if the administration had served edible food and taken a benevolent eye to punk posters and skinny jeans.

Because The Space does not serve alcohol, kids of all ages are able to see shows. I saw actual children lurking on the stairs, though the majority of the crowd for this concert was high school age, freed from their weeknight curfew because all the public schools were closed the next day for local elections.

A girl to my left, standing a cool head-and-shoulders above the crowd, sported a black bomber jacket with the furious slogan “This is Our Culture” stamped in capitals across the back. On the right sleeve, a mirror-verse American flag patch displayed a trapezoid with a crown where the stars should be. (I looked this up later. It’s a Fall Out Boy jacket. I have three or four of their albums but apparently I’ll always be clueless when it comes to looking cool.)

I wanted to ask her about it—What is our culture? And who is invited to participate there?—but I was too conscious of the decade between us, and kept silent. I spent the rest of the opening acts staring happily into the crowd, cataloguing the fierce joy on the faces of the young women surrounding me. I felt like I didn’t know them, but I used to. I want to know them again.

Finally, the headliners came on. I was really there for Frank Iero, their front man, but the music caught me up, the way live music always does. There’s something about being able to feel the drums straight through the floorboards that always gets me. I’m a poet. My art doesn’t let me reach out to touch.

Eventually, it got to be too much. The vibrations hovered over me, then overtook me. They opened me up, and then my whole body was shaking with it, whatever punk song, whatever occupying force Frnkiero and the Cellabration were churning out for the crowd. There was room in my body for all of us, for me and the music and the company, like suddenly I took up less room than I used to, but I didn’t feel cramped, just surrounded. Every day I grow more and more frightened for myself, and the planet, and the wonderful, terrible, incomprehensible people I share the planet with. But shoulder-to-shoulder with this surging organism of rhythm and youth, I felt momentarily comforted.

On stage, Frankie cradled the mike in both hands. “I hate my weaknesses,” he howled. “They made me who I am.” And he didn’t realize it, but he’d just christened my revolution. Because my crowd? We’re full of weaknesses. But it’s what we make with our weaknesses that matters.

So, my advice?

Make something. When you can’t stomach the violence in the news, or the look on your colleague’s face when a student tells her she’s “too black.” When you take a walk and realize all the bees are gone, and the squirrels and chipmunks are dwindling too….write a song. Put it in a play. Build something. Bake something. Give it away. Wherever you’re creating, there’s a revolution. Jefferson Airplane thinks you should.

—Eve Strillacci