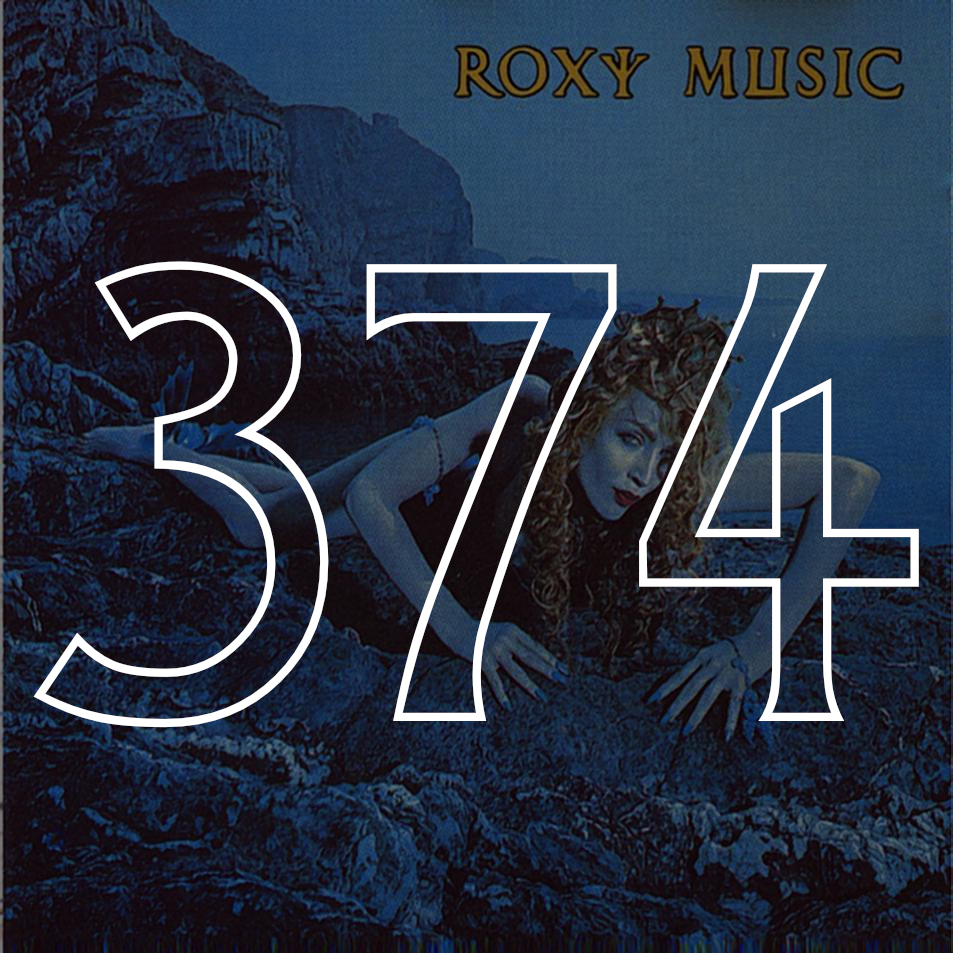

#374: Roxy Music, "Siren" (1975)

What do we want out of music? What do we think it owes us?

These are variations of two questions I’ve begun asking on an almost daily basis the high schoolers to whom I teach English: why are we reading this? Why was it written, and why do we care? Supposing we do at all. Supposing we aren’t just wasting our time.

I think about this problem almost every time I listen to an album, whether for the first time or the thousandth, and it’s a problem that becomes noticeably electroshocked into my consciousness when the album at hand is simply perfectly fine. Not particularly awful, not blowing my mind: just perfectly fine. A-OK. All right by me. When I listen to it, I’m probably shimmying a little, and I certainly like most if not all of the songs. Eric Clapton’s “important” records are great examples of this, as are gauzy singer-songwriter dealies like Tapestry or early Elton. The problem with albums like this—and it’s the same problem I’ve started stressing out my poor unsuspecting high schoolers with—is that they aren’t doing a damn thing to challenge their listener.

But is this what we want out of music? Is this what music owes us?

I’ve just started reading the collected transcripted conversations between David Foster Wallace and David Lipsky during their days together on the former’s Infinite Jest tour. I thought I would almost certainly find the book odorously tedious, but within the first thirty pages, I was unexpectedly struck by something Wallace said about difficult art: “[I]t’s the avant-garde or experimental stuff that has the chance to move the stuff along. And that’s what’s precious about it.” To use Wallace’s vernacular, this isn’t earth-shaking stuff—avant-gardeners from Duchamp to Artaud to Merzbow have either stated or proven the sentiment a million times over—but it’s extremely important, I think, for someone to come along and remind us every now and then of its truth. Oh, right. Music should be moving stuff along. That’s what’s precious about it.

All this is to say that I’m both a perfect and terribly wrong person to be writing about Roxy Music’s fifth album, Siren. For starters, when I woke up this morning, I’d never heard it. It’s got some stellar production, the sax solos are smooth as a strobe light from start to finish, Brian Ferry’s crooning along at his Ferryest: it’s a perfectly fine album. At moments, I’d say, it’s even amazing. “Both Ends Burning,” for example, is so much fun, and the groove it builds seems almost impossible. It’s one of those songs for which they’ve invented the phrase “lost in the music.” I dig it, most sincerely. I’ll probably listen to the record a few more times, even. Maybe I’ll close out a mixtape someday for someone with “Both Ends.” But I’ve got to admit: Siren is no Roxy Music, the band’s self-titled debut which is missing from the RS 500, and which is a better record than any Eno-less iteration of the band could ever dream of making.

Preferring to write about Roxy Music brings everything back to my main point: remembering what music should do, what it owes us, what we hope to get out of it. The album isn’t perfect, for sure, but at least it’s exciting, at least it’s challenging, at least, at its highest points, it sets its sights on the hopelessly weird and cuts the brakes. I want to come back later to the opening track, because it’s incredible, and focus instead on the weirdness sprouting up throughout the other nine.

In the bigger picture, most songs on Roxy Music resemble recognizable genres and pastiches—the countrified swing song here, the fuzzed-out space-rock there—but you don’t even have to peer that closely to find the gorgeous challenges behind the veneer. Most of them, of course, can be traced directly back to Brian Eno: glitches, bloops, stereo-panning electronic squelching. Never totally overtaking the songs themselves—which are absolutely Brian Ferry songs, in all the best ways—but instead working fearlessly to spice them up, to reward the curious listener, to get freaky and funky all at once. “Virginia Plain” tosses you a revving engine as soon as the music drops out, then transitions into a static-wrapped bridge just before ending without warning, almost sporadically. Album closer “Bitter End,” with its electro-spoons and pained sax soloing resting peacefully in the way-way background, comes out sounding like the worst vaudeville show you’ve ever been to (in a good way). “The Bob” starts out sounding like Black Sabbath before devolving into a collage of gunfire, static, and detuned synthesizer, then transitions—logically, somehow!—into a romping, clean guitar solo, which shifts, finally, back into the Sabbath durge. It’s fucking weird. And it’s challenging. And, most importantly, it doesn’t suck.

How do you balance all of these qualifiers? How do you come out the other side of weird art with only minor dings? Well, first, I think, you need a mastermind. Roxy had Eno, and when he left, they maintained the listenability that’s all over their debut record—actually, they wildly improved on it—but they lost the bizarre that made them so extra-exciting. Is Roxy Music the most listenable album in my collection? God, no. “Chance Meeting” follows “The Bob,” and it’s tiresome, plodding, and dumb. All the worst aspects of the avant-garde, right there in your face. Is Roxy Music a little difficult, a little fun, even really damn groovy when it wants to be? All of these descriptions are absolutely accurate. Yes. Most certainly.

Which brings me to “Re-Make/Re-Model,” the album’s opener. It is a perfect song. Easily, without question, the best they’ve ever made. It sounds simultaneously, and still today, like both the utter apex of rock ‘n’ roll and the complete debasement of everything we understand rock music sounds like. After a little ambient crowd noise, the thing practically explodes. The drums kick into a constant two-beat that sounds more like a heart racing than anything you’re ever likely to hear again—it’s an overpowering, almost suffocating drumbeat, beautiful in its dedication. The guitar and saxophone start soloing over and through and with each other with what appears to be little concern for harmonic turn-taking or even the one-upmanship we understand soloing is for. The constant noise of these instruments, in fact, feels more Free Jazz than Hendrix; the only even familial equivalent I can muster is the Stooges, but this is gnarlier, more focused. Somewhere in the mix, of course, too, is Bryan Ferry, glamming it up with his Dracula vibrato. The song’s weird enough as it is—without Eno, it would already be bordering on a shut-it-down noise catastrophe. But Eno’s there, crowded by his reel-to-reel and his unnameable, self-invented electronic monstrosities, blooping and glitching and squelching away. By the end of the song, the structure’s mutated into a more recognizable pattern of a pack of musicians taking turns soloing, and by then, it’s a welcome relief, a terrific understanding of what listeners ache for.

And what is that again? To feel afraid? To feel challenged? To get into the muck and come out with our hearts racing, our skin goosepimpled, our life changed a tiny bit for having heard something utterly unlike anything we’ve heard before? I believe this is true. And if it isn’t true, then I’ve lost track of why we do anything at all. Art should reflect humanity: on this issue I think we can agree. But beyond that, art must first understand humanity as surprising and unlikely, at its best when it’s daring to dare us. Sometimes, we want a little Siren. True. But we need a little Roxy Music if we want to move the stuff along.

—Brad Efford