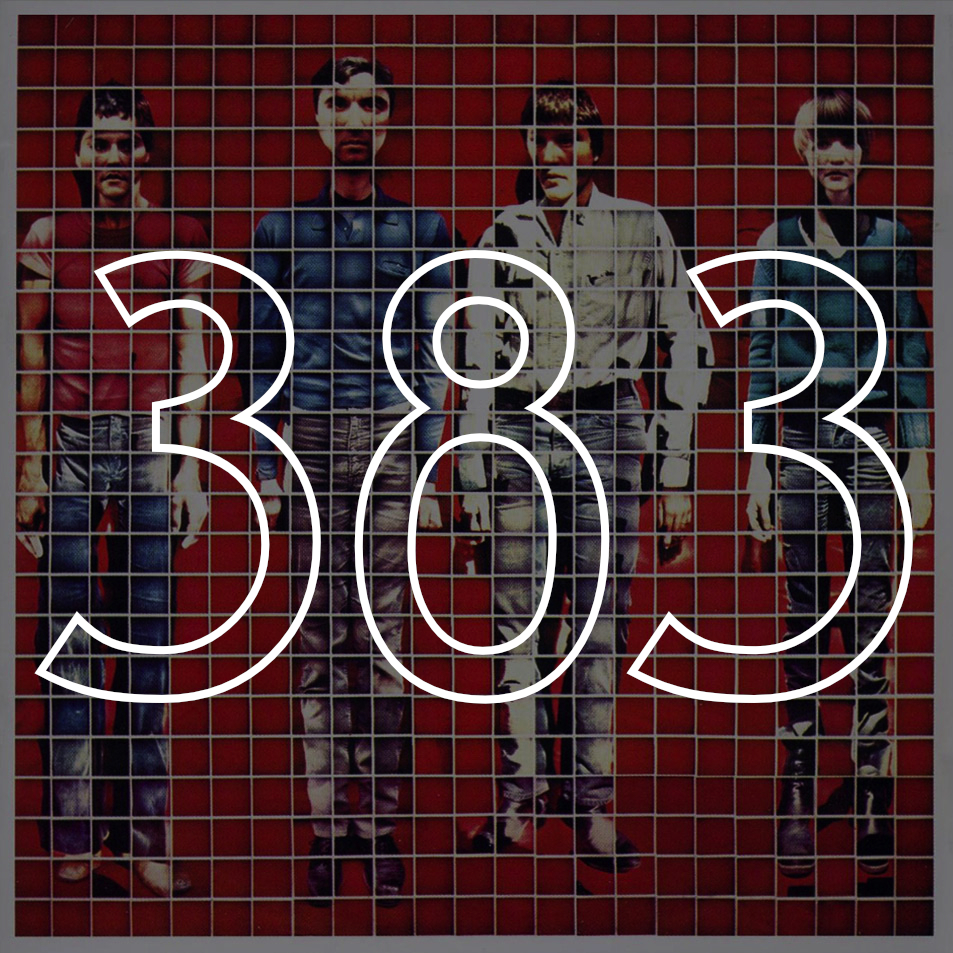

#383: Talking Heads, "More Songs About Buildings and Food" (1978)

We were on a mountain in Switzerland when Beth told me she didn’t think she loved me anymore. I don’t just mean we were on a mountain, I mean we were practically on the top. We’d taken that stupid cog train up that passes through the Eiger and the Monch and then lets you out at some exhibit carved into the Jungfrau, an ice cave, really, with lit-up ice sculptures and fluorescent lights hanging from the low ceiling, and then we’d zipped up our parkas and stepped outside and were standing on top of a metal grate, our mittened hands clutching the railing, looking down, when Beth said it. It was the think that got me, like she wasn’t sure, a child practicing her spelling words, saying, “I think it’s an ‘n’ next, I think so.”

“Jesus,” I said, and she said, “Yeah.” I said, “Is there someone else?” and she shook her head and said, “Just me,” which I didn’t understand at the time.

The night before, in our room in the chalet, she had crawled into bed with me and pressed her cold feet against mine and asked me to warm her up. I kissed her, and she’d said, “Not that way. Do something else.” So I slid my hands under her T-shirt and rubbed them against her stomach and breasts, but she pulled away and said, “Tony, I just think I’m losing myself.”

That was something else that hadn’t made sense to me, and so I’d ignored it, rolled over and went to sleep, and pretended not to notice when she got up and went to the bathroom and stayed in there for half an hour, the thin crack of light under the door marked by her shadow. I thought of that crack of light when we stood on top of that mountain, thought that maybe if I’d gone and knocked on the door, she wouldn’t have said it, but I’ve never been one to dwell on what-ifs.

We had held hands on the train coming up the mountain, but we didn’t on the way back down. We still had three days left in the Alps, and we spent it making awkward conversation about mundane topics. We spent the entirety of the five hours it took us to hike to Trummelbach Falls debating song covers: who did it better, Talking Heads or Al Green, Johnny Cash or Depeche Mode, Beck or Bob Dylan, Jeff Buckley or Leonard Cohen. We argued while trekking past clusters of pine trees clinging for life in thin altitude, making our way through cow pastures, always sure to close the gate behind us, stopping every mile or so for water and to snap a few photographs of the view, which to me looked no different than the view the mile before. By the time we left Switzerland, I was tired of discussing music.

When we returned to the States, we stayed together until baggage claim. Beth reached for her suitcase, a big red duffle bag that I had made fun of when I first saw it but that she had said was easy to find in a crowd, and the veins in her arm popped out like she was having her blood pressure taken. She hoisted the bag over her shoulder, said, “See you around,” and then headed to the cab line. I couldn’t follow her, I didn’t have my bag yet, so I just watched as she weaved in and out of people, the red bag occasionally bumping a shoulder, and then I couldn’t even see the bag anymore. I picked up my suitcase and rode the bus back to my apartment. She hadn’t left anything at my place, which made me wonder if she’d known, before we left, that she’d be ending it. All told, it was easy, or at least as easy as a breakup can ever be. Part of me was surprised at how easy it was, given the whole mountaintop location. I was sad for a few weeks, and then I moved on, or at least I told myself I did.

The truth is, the breakup didn’t destroy me, wasn’t the worst I’d ever had, wouldn’t even still be memorable if it hadn’t taken place on a mountain in Switzerland, which was so goddamn cliché it made me want to vomit. I looked through the holes of the grate at our feet to where the ground dropped away, and heard Beth say she didn’t think she loved me, and a part of my mind went, Jesus, I’m at the edge of the fucking world, literally, and even the thought made me want to cringe at the dramatics.

I don’t think about Beth much anymore. For a while we kept in touch, e-mails to touch base every few months, but eventually those faded. But every so often, that mountaintop comes into my mind. There are some things in life, I’ve learned, that don’t ever leave us, and Beth is one of those. There’s no reason for it—I don’t feel like I have unfinished business with Beth or that she broke my heart and I never fully recovered or that she holds some great lesson I’ve yet to learn—but I’ll hear a mention of Switzerland, or experience vertigo looking out the window of a tall building, and then there’s Beth, standing on that grate, holding her hand out over the railing, palm up, like she’s catching snowflakes or raindrops, even though the sky was clear. I guess you could say she haunts me a little, shows up as a nagging in the back of my head, like that feeling that you’ve forgotten something, only it’s just Beth, saying, “I don’t think I love you anymore,” over and over.

I try to ignore the little Beth voice in my head. When she’s there, when I can’t stop thinking about her, which happens maybe once a year, I try to shut her out. I buy a six pack, and I get drunk watching football, and I tell myself that Switzerland doesn’t matter, mountains don’t matter, and I can get caught up in the game and almost believe it. But after four or five beers, when I close my eyes, all I can see is Beth’s hand resting on the wooden bench of the train, her mittens off, her fingernails bit down to the quick, and as I watch, she rubs her index finger along the side of her thumbnail and picks at a piece of skin that’s come loose, and she tugs at it until it breaks off, leaving behind a tiny dot of blood.

—Emma Riehle Bohmann