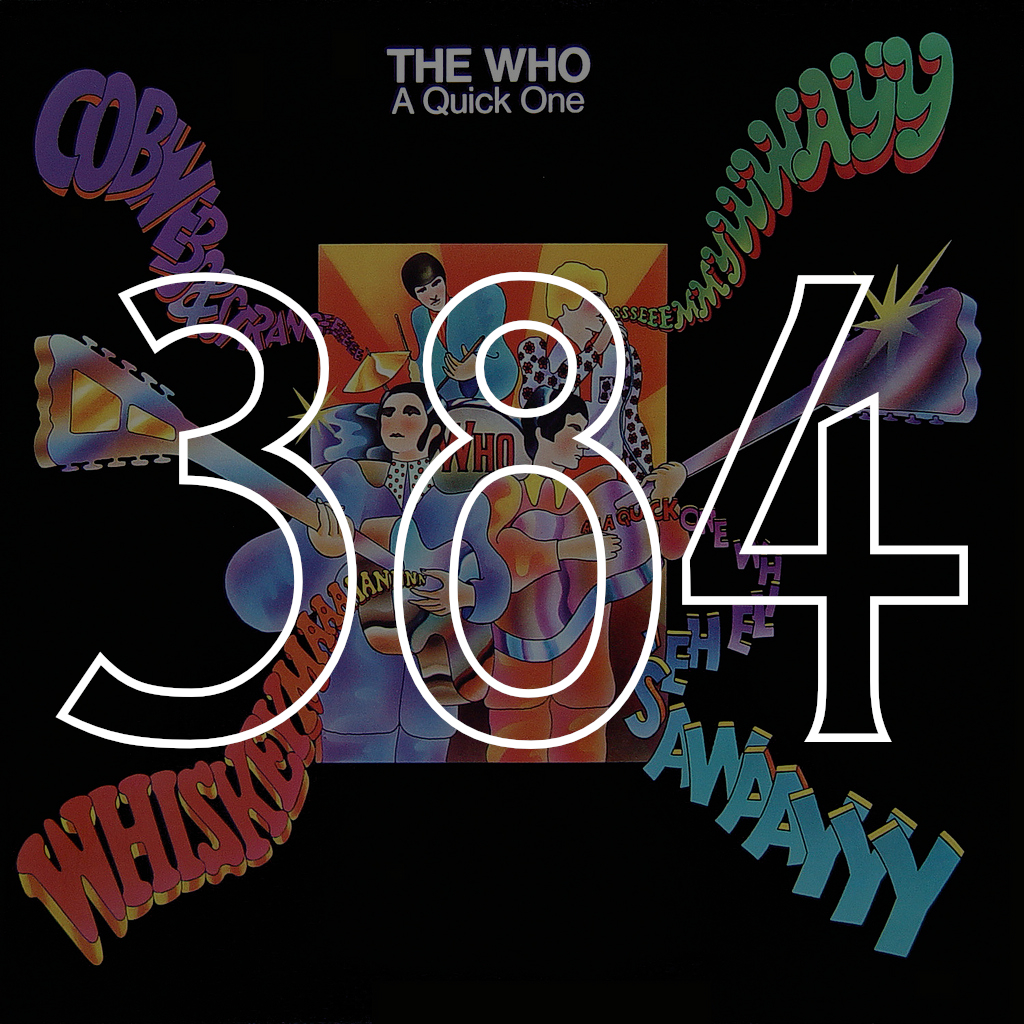

#384: The Who, "A Quick One" (1966)

Most of all, he remembers her scent. When he is driving, he smells only soot and grease, livestock and stale coffee spiked with whiskey. The whiskey, he hopes, will help him forget her scent.

He doesn’t really want to forget her scent.

If he really wanted to forget her scent, Ivor wouldn’t spend so much time trying to remember it—at first, her delicate, floral perfume, easy and light, like he could breathe it in and feel it dancing in his chest, and then, later, that other thing, earthy and humid, like he could breathe it in and feel it dripping, sticky from his ribs. When he’s driving his train, Ivor thinks of her scent and breathes deep through his nose, fills himself with soot and grease, livestock and stale coffee spiked with whiskey, and he can’t believe he ever smelled anything as sweet as she.

*

In the days after their brief encounter, when his train stopped at stations near her town, Ivor asked after the woman. Did her man ever return? If so, did she tell him about what she’d shared with Ivor? How did the man react? Did he leave her? Did he hit her? Did he forgive her for the infidelity? Did she forgive him for leaving? Ivor imagines the man a brute, a cold, callous beast, undeserving of the young woman who had once, not so long ago—but oh, so long ago—missed him desperately and longed for his return. Ivor imagines the woman left her man for having the audacity to leave for so long, imagines her waiting by train tracks, still, after all these years, for the sight of Ivor in his engine’s cabin as the brakes grind.

*

Of course, Ivor knows the man was neither a brute, nor a cold, callous beast. Ivor knew the man from a pub in M_________ they’d both sometimes visit—Ivor, on nights off after delivering freight, the man while traveling the northern half of England selling knives or vacuum cleaners or encyclopedia sets or whatever traveling salesmen sell. Ivor didn’t know the man that well—they’d simply shared a few pints and swapped stories a handful of times. No, the man was neither a brute, nor a cold, callous beast, but that doesn’t mean he was a saint, either. Of the stories the man told Ivor, more than a few involved his occasional infidelities with stray bar maids or customers with whom he was trying to make a sale. Ivor believed the stories for a while, but soon stopped, after the two men, piss drunk after a night at the pub, hired a prostitute to share.

Upon reaching Ivor’s hotel room, after the money had changed hands, the engine driver and the prostitute began undressing and touching each other. Upon noticing that the salesman was sitting on a chair in the corner of the room, still fully clothed, Ivor asked if everything was OK. The man said he wasn’t feeling well. Ivor gestured to his own genitals and said, “Intimidated?” The man, clearly flustered, said, “No. No. Not that.” And Ivor said, “Suit yourself.” The prostitute said, “You want to watch?” And the man said, “I think I should be going,” and then he showed himself out, leaving Ivor to enjoy the prostitute on his own.

When Ivor thinks of that night, he doesn’t think of the prostitute or her scent—cigarette smoke, he thinks he remembers, mixed with something else, something like flat beer—but of the salesman who left and the woman who was undoubtedly the cause of his departure.

*

Because of the drinks, Ivor can never remember if it was that night, or another, on which the man first told him of his love back home, but he knows that the salesman, on at least one night, spoke of his girl and how she struggled with his constant absence, as he was six months into a trip that was set to last for close to a year. When Ivor asked why the salesman needed to be gone for so long without stopping at home, the man referred to travel costs and his desire to make money so the two could marry at the end of the year. But that was just the first time Ivor heard of the girl.

*

After the first time Ivor heard the man talk about his girl, when staying over in towns in the northern part of the country, he’d hear tell of a woman who had grown despondent in the absence of her man. At first, Ivor thought these were different women, all missing their men. The stories placed the women all in different cities and towns across England’s northern half: there was a woman in D______ who had cried for six months straight, her eyes always red, her cheeks slick; a woman in H______ who had grown so despondent that she stopped eating, causing the locals to bring her gifts and food in an attempt to cheer her and keep her healthy; a woman in W______ whose moans of despair had grown so loud, and lasted for so long that, not just the city’s residents but the residents of neighboring cities, grew accustomed to the reverberating thrum of her voice off the buildings and streets around them; a woman in S______ who missed the touch of her man so greatly that her neighbors believed the only way to keep her alive was to find a temporary suitor to satisfy her womanly needs and make her forget, if just for a while, about her absent lover. Ivor chalked these stories up to tall tale and fantasy—engine drivers and other traveling men often tell stories like these when they’re on the road, in part because they like the idea that some young woman might be pining for them, and in part because they like the idea of encountering a young woman hungry for the affections they might offer her.

*

Here’s how Ivor eventually came to know that the stories he’d heard were true, if somewhat hyperbolic, and that they were all about one woman: Ivor was introduced to the woman while staying the night in W_________. He was introduced to the woman, and her eyes were red, and she looked sick, looked weak and, most surprisingly, looked young. Though the stories of the woman were not specific with regards to her age, Ivor had always imagined that, if said stories were true, the women at their centers were old enough to understand the passion and desire they were feeling for their absent men. But this girl—and she was a girl—couldn’t have been a day older than seventeen, reminded Ivor of the Girl Guides he’d seen roving cities in packs, dressed in their blue uniforms, in search of good deeds to perform or whatever it was they did.

Another woman made the introduction, a neighbor and friend of the girl. First, she pointed to the girl across the room, then she informed Ivor that the girl was in need of companionship. Ivor told the neighbor that the girl was too young, that she should seek solace with her family, or perhaps her church, but the neighbor was persistent. Ivor agreed to meet the girl, and the neighbor left to retrieve her.

*

Ivor never told anyone what happened after introductions were made and the neighbor left. Patrons who noticed the pair that night all saw that the girl sat on the engine driver’s lap for a spell. What they talked about, no one knows for sure, because Ivor never told anyone that, once he realized that this girl was, in fact, the love of the salesman he’d spent time with in M_________, he told her that he was certain her man would return to her, and that the man loved her very much.

After an hour or so sitting with the girl on his lap, Ivor led the girl out of the bar and they retired to the room where he was staying. When asked about that night, Ivor tells people that he and the girl had a nap, nothing more—nobody ever believes him—and then he remembers the way the girl smelled. Then he wonders where the girl is now, what her life has been like. He suspects, but he doesn’t know, that she forgave her lover for his absence and, if she told him about Ivor—and he wouldn’t be hurt if she didn’t, but he likes to think that she did—Ivor suspects, but doesn’t know, that he forgave her for the intimacy they shared.

When Ivor thinks of forgiveness, he is at peace because he believes he has nothing for which he needs to be forgiven.

—James Brubaker