#456: Marvin Gaye, "Here, My Dear" (1978)

At a pivotal moment in the great horror movie Pontypool, protagonist Grant Mazzy asks, "How do you take a word and make it…strange?" Our question now is similar but with a twist: how do you take a pop album and make it bad? I don't mean Marvin Gaye has made something unlistenable with Here, My Dear, but that the album sets itself the task of being otherwise than a pleasant or delightful, fun listening experience. It's complicated even to say what I want to say about it—that it's "bad" and therefore great—and already I have wandered dangerously into the territory of the "so-bad-it’s-good" crowd, so I will tread carefully.

Perhaps it's best to start over: Marvin Gaye makes a divorce album. It is "about" the end of his marriage to Anna Gordy Gaye. It is also a fact of that relationship, as he would have to give half the royalties from the album to Anna as part of their settlement. An album of defeat, but one of ruthless experimentation. You can't do much reading about Here, My Dear without running across the glorious couplet "Somebody tell me please / why do I have to pay attorney fees?" It's as if I could stop there and that's, as Keats says, all ye need to know.

But I haven't even begun. Calling the album, as I started by doing, "bad," seems to be a provocation, and it's an old tale told every time someone has a bone to pick about cultural capital. You throw your favorite thing into the mud, really grind it down, then pull it out and in the course of several paragraphs clean it off so it glimmers, authentic as the monument you have now proved it to be. I don't like this kind of writing about things because it's as dishonest as it is ubiquitous. I like Here, My Dear because it seems to be about that very kind of "dishonesty," in a different register, a pop song register, where Gaye doesn't seem to trust the kind of song he is so good at writing to affect anyone anymore. Gaye looks out at the world and sees only himself, consumed as he is by a divorce, and like Catullus mourning the loss of Lesbia, he can only write about sparrows. Well, one sparrow.

The album is myopic, wandering, lazy, monotonous, and far too long to listen to in one go. I've done it twice today, and I don't want to do it again. But an album can do that on purpose, can't it, and what do we do, how do we account for that without first saying, "This thing that seems like trash, it is actually glorious and authentic!" How indeed. To start with, we might invoke Marvin Gaye's previous works, albums further down on the RS500 list and with much more cultural clout, albums like What's Going On, that establish him in the public imaginary as a truly great musician and artist. And I mean, he is, listen to him sing. But there is not so much vocal dexterity or even artfulness of arrangement or anything really as complex as the hits Gaye has produced on Here, My Dear. It is straightforward, with repetitious instrumentations and vocals dubbed presumably to hide the fact that they are half-hearted and wounded-sounding, they sound like a wound, that is, Gaye sounds less like he is singing about being in pain than he does like he is actually in pain. And this is what is exciting about this "bad" album: it is "bad," it is all the things I've said in the preceding paragraphs, because it grasps fairly astutely the structure of feeling of going through a tremendous, relationship-ending process like divorce. Gaye sings, not just "about" divorce, but in a manner adequate to the banality of heartbreak.

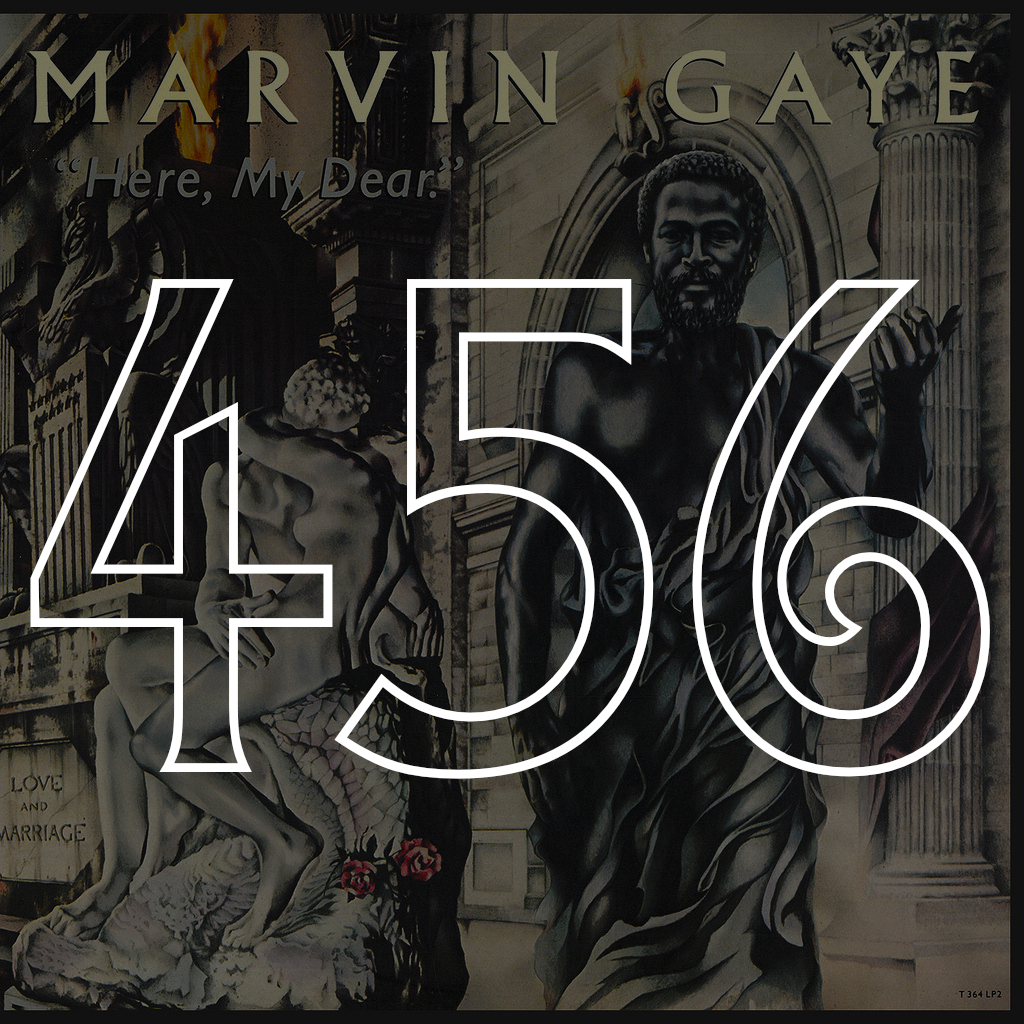

Illustration by S.H. Lohmann

I should probably explain myself. Much typing has been expended on what is basically the sublimity of popular music, the way it invigorates and thrills, all that stuff—sound familiar? So does most pop music. I'm not in the business of making moral judgments, but I'm trying to make a distinction. Here, My Dear sounds like this, and it doesn't. It starts off with the slow build, the layering of instruments, the vocal tracks coming in slowly, the harmonies that devastate and remind you this is the guy who sang "I Heard It Through the Grapevine" and "I'll Be Doggone." But it doesn't have a narrative, it doesn't go from point A to point B and grow and swell and explode and simmer and fade out. It just starts, and then it stops. It calls attention to its plasticity rather than the swooping swerve of Being; it's Apollonian rather than Dionysian, a beautiful and crafted record even as it sets out not to be a pleasant one. And this moves me, and it stays with me, because it makes for a listening experience that makes one uncomfortable and bored, even frustrated, with the artist. It does not ask for sympathy or identification, just time. And when you're done, it's not like you have gone on some kind of redemptive journey. You listened to the album, and there you have it. Glad that's over with. Now what? Gaye refuses even the subtlest hints of narrative, so that the tracks do not develop, they accumulate. Heartbreak, pain, does not have a narrative. It just repeats. That seems to be the great insight here, and it lays bare the repetition at the heart of pop music while turning it against itself by making of that repetition an instrument of antagonism (by the artist, toward the audience) rather than one of pleasure and easy listening. And when I say this, I don't mean that this is a "deep" album, requiring intense and art-competent listening. I mean that it is actually difficult to listen to, the experience of listening to it takes effort and gives little in return. All the fantasies of the enlightened and thoughtful listener are set aside. It just happens, and keeps happening.

Maybe there isn't any good way to write about Here, My Dear without sounding like I'm puling about authenticity. Gaye doesn't bother to put on an act, he doesn't affect feeling, because he knows that doing that would only make it an album about the act he put on, rather than the actual feeling. It's hard to talk about dissimulation in an album so self-involved as to worry about how its maker won't get any of the royalties because of the divorce. What's the point? asks Gaye, with none of the grandiosity of punk, or the sly hopefulness of the 1960s. At the end of Pontypool, Grant Mazzy intones dramatically, "It's not the end of the world. It's just the end of the day." Imagine Mazzy's talking about heartbreak and you've got a good summary of Gaye's album.

—David W. Pritchard