#457: My Morning Jacket, "Z" (2005)

My name is Z. I have been here some years. I cannot say how many revolutions. There was a time when I counted those things.

If one’s life is a series of ripples radiating outward from, and back into, an original centerpoint—that is, a series of widening circles drawn around a dense and mysterious core, some “I” that blossomed forth from an unknown origin-point in the cosmos—I am now walking the outermost, and widest, circle. Beyond it, there is an unknown space, darkness raveling out into more darkness. That same darkness out of which I emerged, in the beginning.

I came here for the azure sky, the winter light. When a man undertakes silence, he needs a great deal of distance into which he may cast his thoughts, as casting a line into the sea.

The thoughts are not bait, not a hook. They are the line, reeling out, nearly invisible against the blue. There is nothing to catch. It is merely the action of casting and reeling that interests me.

I remember a day long ago, before I came here, when I was very ill. It was a cold, bright day. I was walking down the street. There was a man I came across, in faded denim, hair to his shoulders. He asked me for money and I gave it, knowing as I placed the coins into his palm that I could never repay him for the blue of his eyes, that flood of desolation. What was washed clean inside of me.

I would that I could become threadbare and held to the light, that the light might strike my skin as a golden husk.

I have been thinking of the fields of goldenrod in August, the corn huskers lotion that my father used on his face and hands, his worn flannel shirts. The smell of leather, the horse’s hair pulled taut and bowing across a fiddle’s strings. The sun that struck the horse’s mane, the dust of barns, and of the grain silos filtering almost vertical beams of light through golden wheat. Unless the grain of wheat falls into the ground and dies, it remains alone. But if it dies, it bears much fruit.

There are so many selves, each one peeling away, translucent as the skin of a snake. I no longer remember who I was, if remembering is re-inhabiting, which it isn’t. Remembering is trying to apprehend the form of a ghost in one’s house. It is peripheral, sliding along at the edges, the sensation of something behind you, a shift of the air. Let us not say remember, then. Let us say that the past is a presence of a different substance, an unusual quality of light.

Past selves are smaller circles within the radiating ring of circles that make a life. All of the past is encompassed, then, within the present. Between each circle there is a distance (a death?). An axis (+) that transects each circle at four points; these are paths that lead into and out of each circle. One cannot travel these paths, from past to former self, with the corporeal body. One must travel these paths as a spectral form of light. One must travel the dark tunnels of time as a ghost travels up and down a hallway.

When the sun begins to sink in the evening, I have to be out in that light, moving across the ridge. I like to see the distances closing in, pale yellow washing the horizon, bright flare of orange, that fast slip of light in the West. (Do the distances close in or grow greater?) I walk, watching the vesper sky, until dark, when diamond stars begin to shine forth as dancers leaping onto an empty stage, and seeing becomes a kind of listening. Coming back across the ridge, I hear the sound of my boots against the frozen earth, as a shadow in my ear, cracking.

In the winter of his 35th year, severely ill, Vincent Van Gogh went to the south of France for refuge, to the city of Arles. He was enchanted by the light of Arles. He washed the somber earth tones from his palettes and mixed new colors. There, out moving in the light each day, he painted his most illuminated pieces, dappled in yellows, mauves, and ultramarines. Van Gogh wanted his work to lead to God.

I wonder if he heard a great silence, before severing his left ear with a razor.

Afterwards, at the asylum in Saint-Rémy (a former monastery), in the last months of his life, he composed his heart’s masterpiece, “The Starry Night,” that painting with so much darkness and music in it.

I want to point a finger at the moon, then cut my finger off.

Nights, I dance with the paradoxes. Dawn is as a great weight pressing down upon me— I struggle mightily under it.

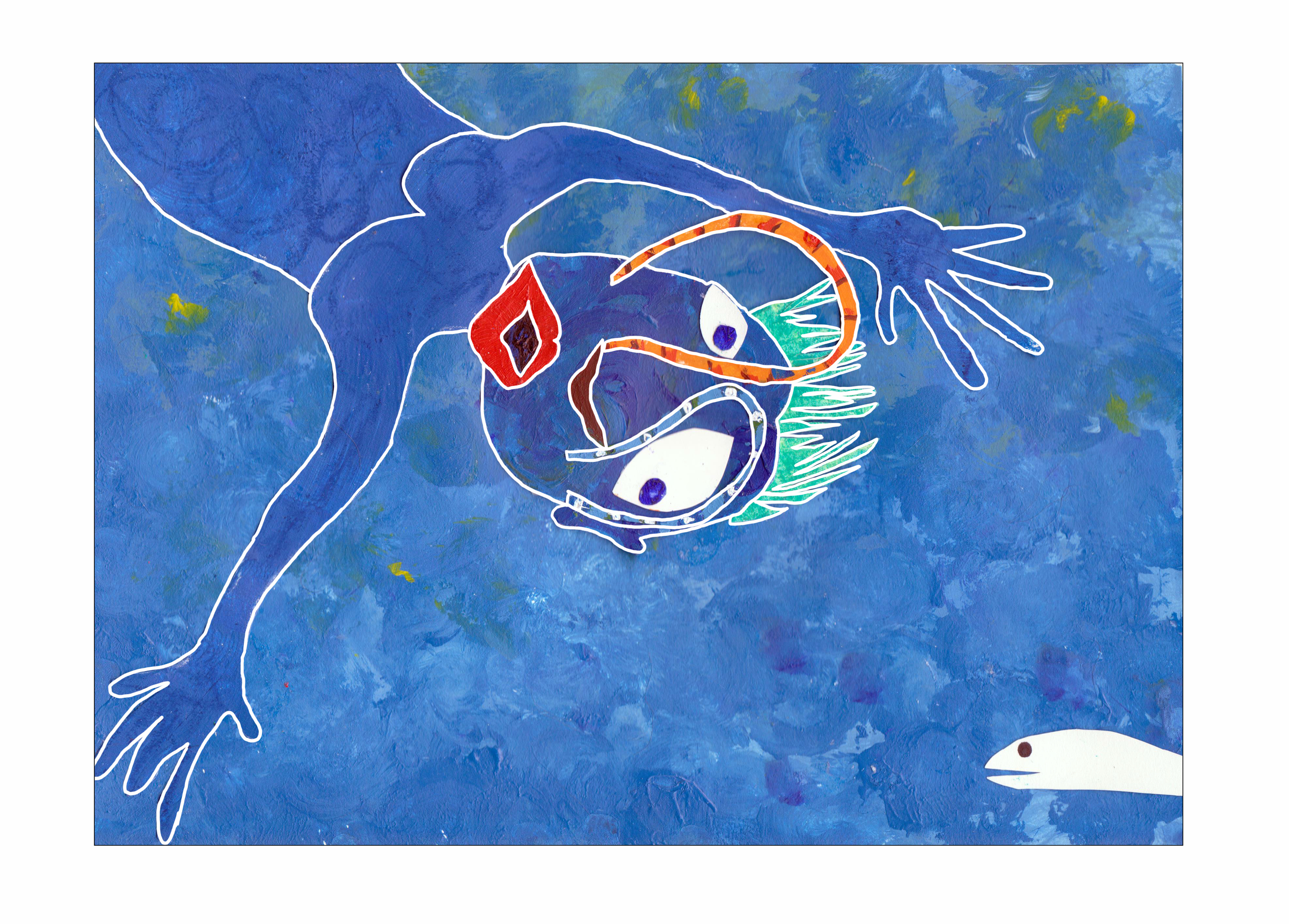

This winter my thoughts have turned to the sea. Once, when diving at the old shipping port, off the coast of where I lived for a time, I saw an eel hunkered beneath the concrete wall of the port. I descended towards it. It crept out, moving like a slow tremor. It looked at me, swaying back and forth like an electric wire ungrounded. Its eyes were the black sparks of the sea. The eel and I looked at each other for long minutes there, a kind of silent music between us, far under the shimmering surface, where tumultuous light was breaking among the waves.

Illustration by Annie Mountcastle

Van Gogh wrote to his brother: “I am seeking. I am striving. I am in it with all my heart.”

I should like to revisit the sea, to submerge myself in the salt water. To hear, again, that rhythm, the steady swell and break, earth’s metronome, as an uninterrupted and endless sigh. I remember long winter days at the shore spent swimming. Not swimming but floating on top of the rising waves. How I was lifted up and over them, the weightless drift of my body. A continuous effortless motion. And inevitably, when the tides began to shift, how I would find myself suddenly swept into the trough of a wave, how the body would struggle for one brief moment against it then give itself over to the pull. It was a blinding surrender that was not without fear but was surrender nonetheless. How the body, then, would be taken away—to give in to that, how I would lose myself completely to the wave, to be rolled and rolled into it, that ecstasy of union, to lose my footing, my direction, then to be pummeled and knocked against the sand, to come up on the shore breathless, as so much seafoam.

I have not, as some say, abandoned the world, but in fact am plunging myself deeper into it.

Van Gogh’s paintings from Saint-Rémy, his last and most beautiful paintings, were full of swirling. The edges of the individual, separate marks of color that distinguished his earlier paintings began to soften, swirls of light merging into darkness. Boundaries between cypress, field, mountain, and sky became blurred. He painted what he could see from the cell windows of the asylum: golden fields of wheat with skies of blue above, birds flocking. He wrote to his brother: “I do not need to go out of my way to try to express sadness and extreme loneliness.” Also that he was entirely absorbed “in the immense plain against the hills, boundless as the sea.” He died soon thereafter.

It is said that no man is an island.

On my walks in the evenings, when yellow light is seeping in behind the bare branches of the woods, I have seen an elk hulking between the trees, standing still, brown as the bark on the tree trunks. I have seen the elk as one sees an elk in the trees: as a remnant, or future, self.

I am the alpha and the omega. But there is something else: a movement that precedes the first letter, a shadow trailing off behind the last. Something at the edges, wordless.

Another memory of long before I came here, before I took the vow: walking in the back alley, where starlings would gather in the tree of heaven, quiet as seedpods rustling on the branches. When I walked underneath the tree, how they would disperse on the air in one great tumbling wave, rolling across the sky, all together, as if swaying to some silent music. How they plunged and swirled into circles and arcs, and I would feel the trembling of the air on my upturned face. Their small singular bodies formed a swelling symphony the beauty and grace of which even they could not understand, and I knew then that the world was not just graffiti and couches with broken springs and the pungent juices fermenting in the bottoms of garbage cans but that it was this, too. This swarm of wings, held together and cleaved apart in each moment by something unseen, unknown, mysterious.

I feel I am coming to the end. I do not consider myself at the edge of the world but rather in the dense center of it.

—Holly Haworth