You might not think of Summersville, West Virginia as a prime location for an award-winning show choir (who would?), but Daniel Seacrest, Josh Simpson, Brandon Hutchinson, and I won the Show Choir Invitational two years in a row, and Elton John was a part of that legend. Senior year, we had three Elton songs in the line-up: “Philadelphia Freedom,” a piano cover of “Your Sister Can’t Twist (But She Can Rock ’N Roll),” and “Harmony” from Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. We’d take our places onstage, blue sequin vests glittering in the spotlight, and wait for our director, Jason Hypes, to start playing. And then, before God and our parents, we’d sing, “Oh, Philadelphia freedom, shine on me and I love you / Shine the light through the eyes of the ones left behind!” Were we goofy? Yes, sure. Four white trash teenagers singing Elton John. We could have sung anything we liked, but Elton—at least our idea of him—was what we liked, and even if we didn’t know what he was singing about, it was different.

The evening after, our homecoming concert took a turn for the worse that I haven’t really told anyone about because I still don’t know what to make of it. Josh had just gotten a new pick-up, a graduation present from his dad, and said he wanted to take it muddin’ down at a vile place people called “N-word Hole.” He did this in the dressing room at the high school theater, shirtless, as if to show off his physique. He was tall, with a square jaw, and these arrogant blue eyes. His favorite hobby—his only hobby, as far as I knew—was lifting weights.

I changed out of the electric blue sequin vest, stripped to the waist, wearing only a pair of boot-cut jeans. I had long thin limbs, huge hands and feet, but thin and wiry legs as if I’d descended from some type of gibbon. Stupidly, I asked, “What’s N-word Hole?”

“A grave where they threw lynched slaves during the Civil War,” Josh said.

“You’re joking, right?” was the best I could come up with.

“They say it’s haunted,” Daniel said, changing into a faded T-shirt and jeans. Daniel came across as a conservative, corn-fed country boy, but he was good and decent. His fingernails and knuckles were blackened from his part-time job at the gravel plant. His posture—I could reconstruct it just from memory alone—was perfect, proud, and even after his accident he was impeccably built, with strong musculature. “It’s behind the Go Mart in Sugar Grove.”

“I-It sounds like someplace we’re not supposed to be,” I said.

“It’s not just someplace you’re not supposed to be,” Daniel said. “It’s trespassing.”

I wasn’t a troublemaker, as far as the others could see. I imagined being arrested for trespassing. Cops would be dispatched to the place to round us up and take us to juvie.

“It’s not trespassing, so let’s go,” Josh said. “Brandon, you coming with?”

Brandon was watching Josh as if he’d been placed there by some cosmic force to enjoy it all. Josh, you see, was bringing something out in Brandon. “Sure,” he said. “Why not?”

Josh gave him the kind of look you wouldn’t expect from a friend, his eyes fixed on Brandon’s face, his lips curled into a sneer. “Brandon, you’re gay, Brandon.”

There stood Daniel, looking at Josh with uneasy disapproval.

I didn’t know Brandon as well as I knew the others. His features were more feminine, and he had a lisp, so he didn’t even have the advantage of fitting in with Josh and the good old boys. He’d spend his lunch not on the basketball court or the parking lot, but sitting with a few of the outcasts, mostly girls, in the lunchroom. And, while it’s harsh to say it, this is what I’m getting at: some people, born into their circumstances, are doomed from the start. Brandon, gay, growing up in the red center of Appalachia, the heckling and hazing, had a tough row to hoe. I can’t imagine trying to be oneself in Nicholas County. The courage it must take to do so.

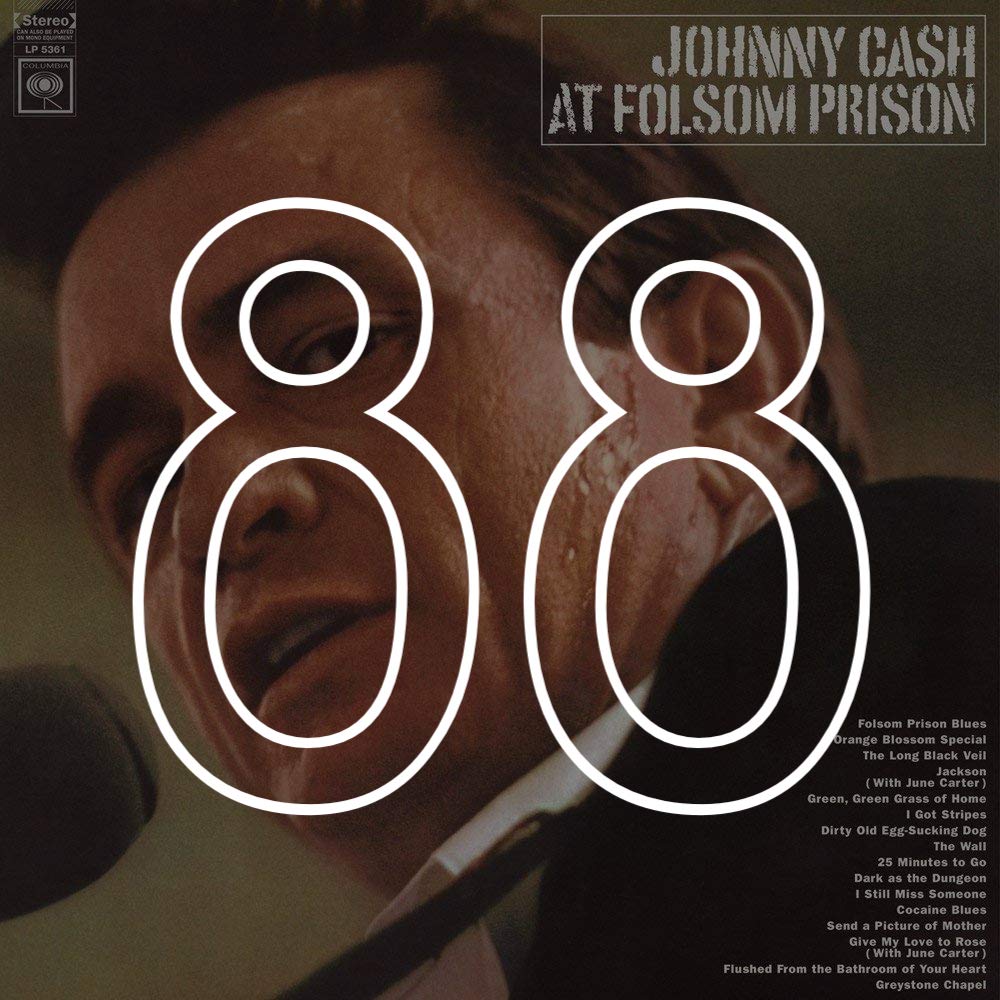

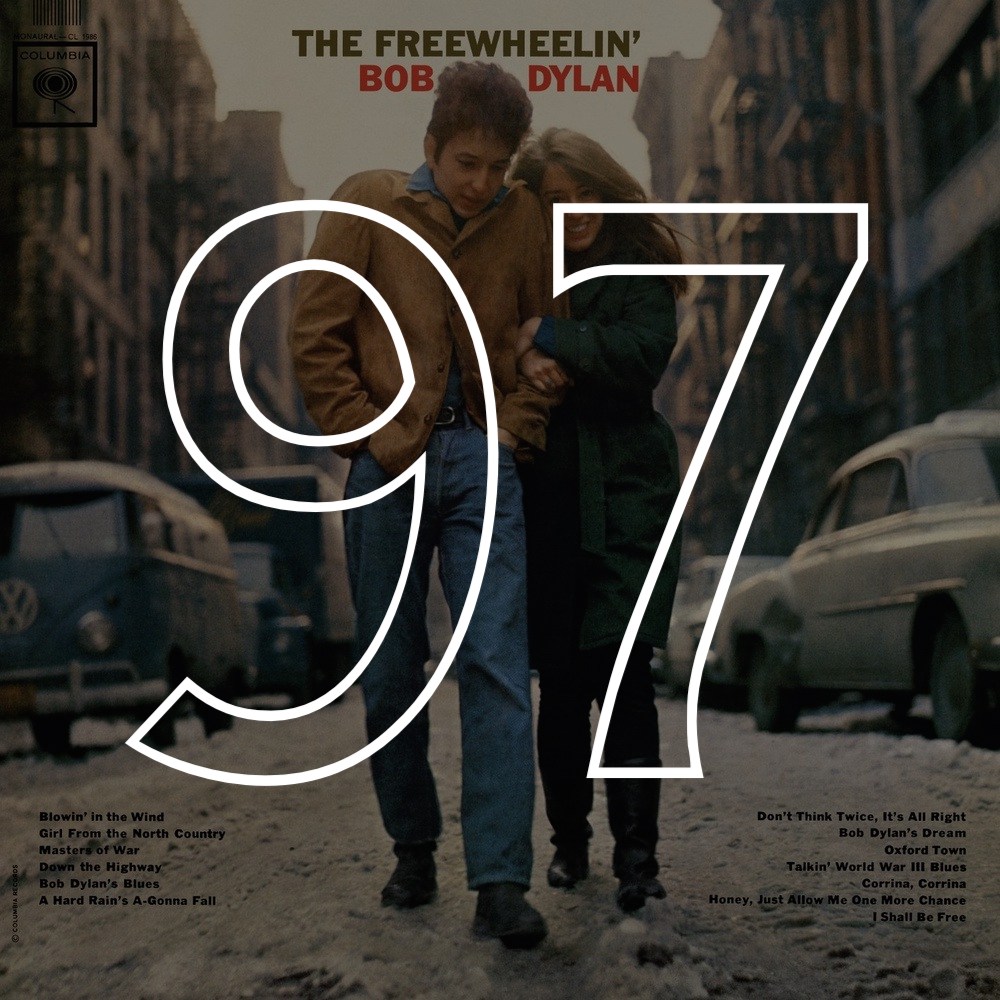

Soon we were driving out to N-word Hole. Daniel brought his Goodbye Yellow Brick Road CD and we were singing along to his favorite track, “Roy Rogers,” still buzzing from the concert. The clouds were peeling back from the moon when we passed the old Go Mart at Sugar Grove, and then we hit a gravel road that ran perpendicular to the mountain, which had probably, at one point, acted as a logging road. Eventually, we turned off the music to concentrate on the road. Josh drove deeper and deeper into the mountain, across a creek and through a gate, until there was no road left. Nevertheless, the truck continued, and Josh winced every time a branch grazed the fresh paint. At its lowest point, the creek bulged into big, muddy pools, forming a swamp. Josh floored it and the truck rattled into the pools, splashing mud up onto the windows of the truck. The pools were waist-deep, but the monster truck had no trouble navigating them. Josh would rev and Daniel, Brandon, and I would holler, grunt, and whoop.

The truck jumped the creek and grumbled up the opposite bank and then down another hill. At the bottom, Josh stopped and put the truck in park. “There it is.”

At first I saw nothing out of the ordinary but a dark scatter of mountain laurel, but then I noticed the truck’s high-beam headlights illuminating a giant black sinkhole in the center of the woods. Josh got out to get a better look, and Daniel, Brandon, and I followed. I inhaled a stink of rotten roots and mud, but there was something else. There was something in the air that wasn’t natural, a thick, fecal odor mixed with an almost chemical petrichor. Even though it was just an urban legend, I thought this was an awful place. Images accumulated in my mind: a mass of faceless human suffering, rigid and naked, no trace of human decency, the worst of what we have been and still are. It felt like there was something dark settling over me.

“Come on,” Josh said, “get back in the truck.”

Josh was itching at the chance to go muddin’ in this sinkhole, so we all got back in the truck and we peeled out and then went round and round, hollering, grunting, and whooping, for what seemed like a long while. Josh turned to look over his shoulder, grinning at Daniel, moving the gearshift up a notch with a flourish. The truck pitched unsteadily and slid tail-pipe first into the sinkhole. Josh hit the gas and we smelled burnt rubber. We went nowhere. There was no yelling, but a chill spread through the cab of the truck, a silence.

Josh looked up, blankly, holding the steering wheel as if it were his junkie brother that he had just strangled in order to get some point across. “I think we’re stuck.”

As I sat there in the backseat, I heard something. Tump? And then, after a long silence, another one—“tump?”—and I felt the back of the truck sink further into the mud.

“I think we’re sinking,” Brandon said. “What do we do?”

“I don’t know,” Josh said. He was flabbergasted, and he tried to speak lightly, a cautious approach, in case the truck sank further. “My dad is going to kill me.”

I started laughing in the face of the gentle hysteria. “This is bad, just bad.”

“It’s not funny, Joey. This truck. Is completely. Ruined. Shit! Do you get that?”

“Does it matter if we can’t get out?” I said.

“Of course it matters, dumb shit,” Josh said. He laughed, and Daniel laughed a little, too, though I wasn’t exactly sure what was funny to him. Josh was trying to concentrate.

Daniel gave Josh a long slow look. “Let’s try to pull it out.”

In the next moment, we were trying to get the truck out. Josh had taken off his shirt (because it was April and still chilly at night, and “It would be better to put on a dry t-shirt instead of a wet one”) and was down in the sinkhole, trying to clear enough mud for the tires to grab. We were stuck in that godforsaken hole, bickering and getting depressed. The four of us were lined up along the front of the grill, trying to pull the truck out of the sinkhole, when Brandon’s hand accidentally grazed Josh’s.

“Get your hands off me, Brandon—god,” Josh said. “Fucking faggot!”

Brandon stood and backed away, apologizing, saying, Oh, it was an accident. He was nonplussed, perhaps a bit hurt by it. Then there was a silence. A long silence.

“Brandon, you can be gay if you want to, buddy,” Daniel said, clapping him on the back.

“No, he can’t. I don’t want a queer hanging around me!” Josh said.

“What’s your problem? You’ve been singing Elton John the whole semester.”

Josh wiped the back of his hand across his eyes, and dried the mud on the front of his jeans. He looked at Daniel. He was confused, which I guess I understand.

“Elton John is gay, dude,” Daniel said, as if it went without saying.

I thought, Wait a minute—Elton John is gay? I was young, you see. Seventeen was young, especially in West Virginia. Suddenly I gained something we call clarity. I had thought that gay people were just something on TV—that there was Jack from Will & Grace and people on a show that I was forbidden to watch, Queer Eye for the Straight Guy, on Bravo. That there were people like my uncle Darrell. I gained a new awareness, a heavy one, through which I understood all at once what my mom had meant when she said there was something “wrong” with my drama teacher, Mr. Reeves. Now it seems incredible to me that a satori like this can occur today in the 21st century. But consider the place, consider how seldom outsiders turn off onto the gravel roads that emerge without warning from the woods. And when those backwoods roads turn into dirt roads still deeper in woods; and when those in turn give way to roads that aren’t really roads at all, deserted for weeks at a time. It’s not hard to see how a kid growing up in the dark hollers can be virtually unaware of another human being’s existence.

“Yeah, Josh,” I said, shucking off my surprise. “Elton John is gay. C’mon, dude.”

“No,” Josh said. “Elton John is not gay. Now get behind the truck and push—”

“Yeah-huh,” Daniel said. “Philadelphia Freedom? The City of Brotherly Love?”

“Prove it then!” Josh shouted. “Prove to me that Elton John’s a fag.”

It was the way he said the word that made me understand who he was. His face was terrible in its anger, his cheeks gone oxblood red, spittle shooting from his mouth.

Daniel looked at Brandon reassuringly. “Brandon, God loves and welcomes you, man. If it’s okay for Elton John to be gay, then it’s okay for you, too.”

Josh looked at Daniel in disbelief and let out an operatic scream of anguish and then he went back to trying to rock the truck out of the sinkhole.

After a beat, I looked at Brandon. A curtain had fallen across his face, and he was shaking. With a voice gone rusty, he said, “Whatever.” He looked vulnerable standing there against the night. I looked at this tableau for a long time even though he wouldn’t look at me. I thought that I understood his grief a little more, but I could never, given a million lifetimes, understand what he must have gone through. You see, this was just one night.

At some point, Brandon wandered away. I tried to convince him to stay, until we got the truck out, but he went on. We eventually got the truck out of the sinkhole, mud-caked from head to toe. On the drive back, we drove in silence, looking for Brandon. I thought I saw him once, walking along the side of the road, but it was an old woman with pale yellow hair who looked uncannily like Brandon. Josh pulled up next to her and rolled down the window.

Have you seen our friend, we said. Blonde hair. About this tall. You seen him?

She started laughing. Who is it? she said. Who’d’ja say you were lookin’ for?

We whispered the name. We said the name again. Said out loud the name this time.

We saw Brandon at school a couple days later. He hadn’t moved away, or disappeared, but he had changed somehow. He was no longer Brandon. We rarely saw him. He rarely spoke to anyone, no more than was absolutely necessary. The show choir was effectively disbanded. Josh became interested in other things, as well, and pretended that Brandon didn’t exist.

Daniel felt sure that Brandon had made a kind of magical escape into some “yellow brick road,” as he called it, a fantasy world that Brandon had made up and now lived inside. The real Brandon would be a mystery to everyone, wherever he might be.

—Joe Halstead