Live from the Shrine Auditorium in Los Angeles, California, it’s the twenty-sixth annual Grammy Awards, with your host, John Denver!

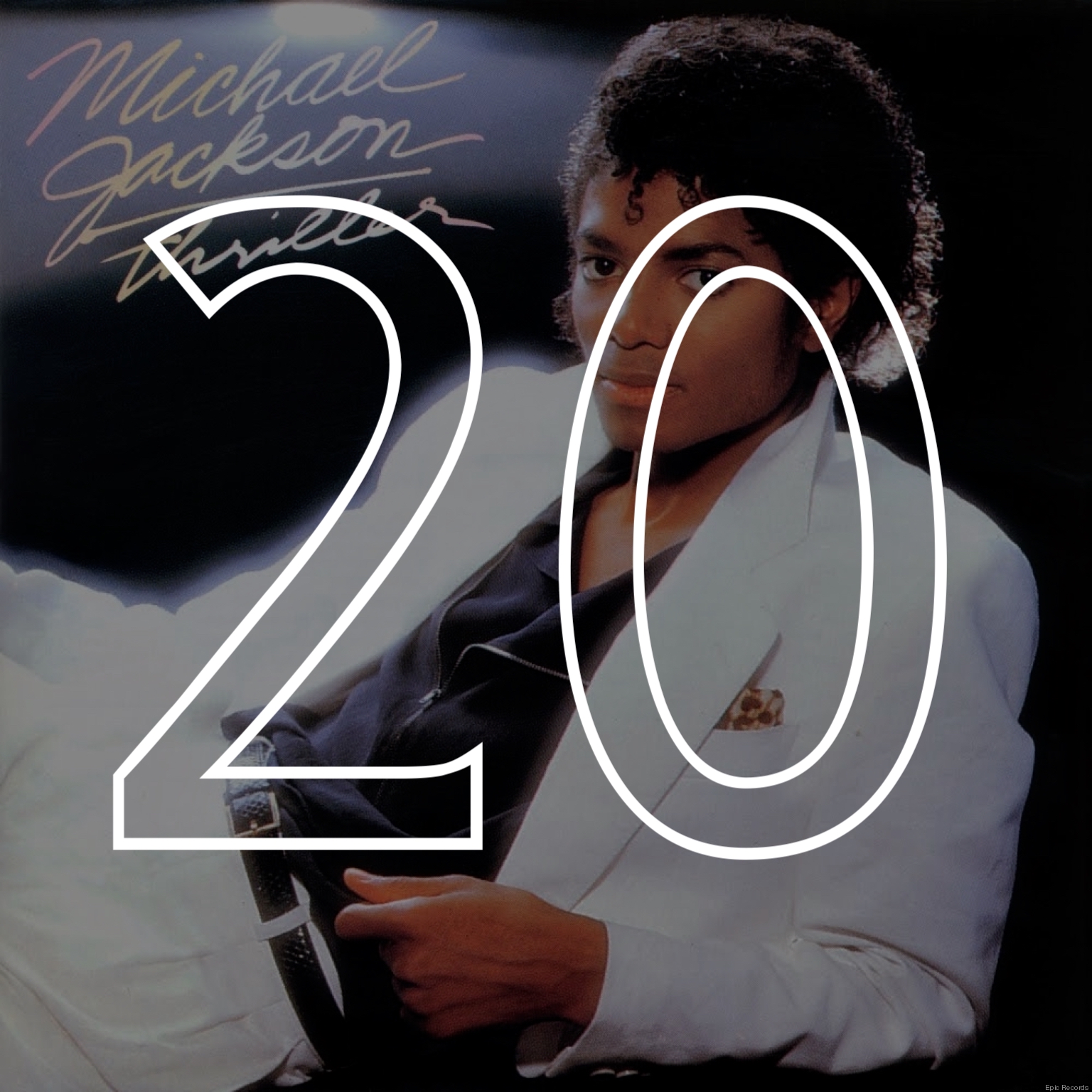

“The big words this last year were video…Boy George...and Michael...”

Audience: “JACKSON!”

As the audience shouted the answer back, the camera cut to Michael, gotten up as the Rhinestone General, moving one seat over. That’s where the camera was.

*

“To announce this year’s Producer of the Year is last year’s Producer of the Year—ladies and gentlemen, Toto!”

Five nondescript looking guys in tuxes announced one nominee apiece. One person was actually nominated twice: Quincy Jones by himself, for producing James Ingram’s It’s Your Night, and Jones with Michael Jackson; the latter was credited as co-producer of the four Thriller songs he’d written. A year earlier, Toto had accepted Grammy after Grammy—six in total, including Album (Toto IV) and Record of the Year (“Rosanna”). The big winners, Quincy and Michael, hugged the members of Toto, all of whom played on Thriller—and plenty of other albums, since the band’s members were all highly in demand as session men.

Thriller was the culmination of Toto’s heavily worked L.A. session style, a hallmark of both black and white pop in the seventies and eighties. This smoothly played stuff was, as Mark Rowland and Nelson George noted in Musician, “the only black musical style that consistently dented white Top 40 radio” in this period. The obverse was also true:

The Doobie Brothers and the Eagles, who started as rockers and country rockers respectively, were recording in a “beige” style, similar to [Earth, Wind & Fire] and the Commodores, before their demise. Even Toto, the quintessential L.A. studio group, appears regularly on sessions of top L.A.-based black stars—including, of course, Michael Jackson. None of which should surprise. L.A. is the official capital of the entertainment industry and its commercial standards must reflect that fact. Since provincialism and eccentricity simply won’t sell in Middle America, edges must be rounded and homogenized, and if that sometimes makes the L.A. sound seem less a conduit than a Cuisinart, so be it.

Toto outtakes, keyboardist David Paich noted, went “on Michael Jackson albums...Steve [Porcaro, the band’s other keyboardist] had this song ‘Human Nature’ and he brought it to Toto, but we said, ‘We can’t use it right now. We’re into songs right for stadium rock situations.’ And sure enough, I turn on my TV and there’s Michael Jackson singing ‘Human Nature’ in a stadium. It backfired on us.”

By the 1984 Grammys, Toto’s day as a major band was basically over. The critics who’d called them names—Rolling Stone had memorably compared the sound of Toto IV to “a Velveeta-orange leisure suit”—had nothing to do with it. Guitarist Steve Lukather would refer to Toto’s prime as “the MTV horrific years, where they tried to dress you up like a fuckin’ clown, you know? You know, when I came up, I didn’t realize you had to be an actor too.” But Michael Jackson did.

*

“The main job of the producer,” Jones said at the podium, “is to produce, and see that everything works. And we’d like to thank the people that make this work.” He pulled out a folded-up sheet of paper from inside his jacket. “We’d like to thank Paul McCartney, Eddie Van Halen, Vincent Price, [engineers] Bruce Swedien, Humberto Gatica, Donn Landee; sixty-two musicians, the best in the world; twenty-two of the best singers in the world; the voters of NARAS, Epic Records, the disc jockeys, Freddy DeMann, Ron Weisner; the songwriters, without whom we couldn’t fly: Rod Temperton, Michael Jackson, James Ingram”—a pause; the young girls in the auditorium’s balcony squealed at the very mention of Michael’s name. Michael grinned, relishing it.

Jones went on: “Steve Porcaro. John Bettis. My wife, who chose to take care of me rather than pursue her own career”—Quincy giggled—“and our family and I love her. And Michael Jackson.” Shrieks up. “And his beautiful family, and I also want to thank him for co-producing three of the sides [an old-fashioned term for a single track] on the album.

“And,” Quincy added, “one of the greatest entertainers of the twentieth century.” They embraced. Cut to a tight close-up of Peggy Lipton Jones, the woman who put her career on hold so her husband could make the biggest album ever made. She smiled savvily. They’d divorce six years later.

Other people getting credit for his work seemed to gnaw at Michael at the time—understandable for a young man who’d been carrying his family on his back since kindergarten. His suspicion even extended to his strongest musical ally. Though Jackson received credit as Thriller’s co-producer, CBS president Walter Yetnikoff alleged that Michael called him the night before the Grammys to insist that Jones “shouldn’t get a Grammy for producing the record, I produced it . . . go to the Grammys, tell them to take Quincy’s nomination off, I want to be the only one getting the Grammy for producing the record.” Walter responded, “Go to the goddamn Grammys, Michael, and act like you’re happy.”

You might have figured that Thriller’s becoming the most ubiquitous piece of music ever recorded would soothe young Michael’s emotions. Not entirely. Three weeks prior to the Grammys, on February 7, the Guinness Book of World Records threw a party for a thousand guests at New York’s Museum of Natural History, where Michael was the guest of honor. The occasion was Thriller’s inclusion in the year’s edition as the bestselling LP ever—23 million copies. “For the first time in my entire career,” Michael said, “I feel like I’ve accomplished something.”

*

“For Album of the Year, the awards go to the artist and album producer.”

The Beach Boys were at the podium. Two months earlier, founding drummer-singer Dennis Wilson had drowned in Marina del Rey; as many pointed out, he’d been the only Beach Boy who surfed. When Dennis died, his blood alcohol level was 0.26, double the legal limit. “When you’re sixteen years old and you’re literally handed millions of dollars, you get crazy,” frequent Beach Boys session drummer Hal Blaine said of him. The Wilsons’ imbroglios could make the Jacksons seem serene.

But the Beach Boys acted nonchalantly as they announced the Album of the Year nominees—apart, of course, from the spacy Brian. “There’s no winner!” he barked upon opening the envelope; “Awww” the band responded in unison (not harmony). “Thriller!” Brian yelled. He knew the joy of writing songs that everyone wants to sing, and the darkness that can accompany it.

This time, Michael called up “the best president of any record company, Walter Yetnikoff—where are you? Come up here, Walter!” They embraced, and the bearded exec sonorously announced that Thriller was, officially, “the biggest-selling album in the history of music.” He did it so Michael and Quincy didn’t have to. A coarse loudmouth who’d do the yelling was just what Michael needed. That summer, Yetnikoff would tell Billboard that Michael “would be totally qualified to run a record company if he so desired.”

Back on the microphone, Michael tipped his hat to Jackie Wilson, who’d died the month before. “He’s not with us anymore, but Jackie, wherever you are, I’d like to say I love you and thank you so much.” Wilson had been one of R&B’s most electrifying performers in the fifties and sixties, first as Clyde McPhatter’s successor as lead singer of the Dominoes. In 1958, Wilson met another Detroit native, Berry Gordy, and recorded his song “Lonely Teardrops,” Jackie’s first solo hit. But Wilson was on Brunswick Records, a Chicago label whose owners favored middle-of-the-road pop treatments over the tougher, more soulful sound that Gordy would take to the bank with Motown.

On September 29, 1975, Wilson suffered a heart attack while performing “Lonely Teardrops” at the Latin Casino in Cherry Hill, New Jersey. In a coma for a year, Wilson incurred brain damage that kept him living in nursing homes until his death on January 28. Michael Jackson had watched Jackie Wilson intently as a child, vowing to match his impossibly lithe physical grace—and not replicate his lack of power over his own career and fate.

*

“You’re a whole new generation, you’re lovin’ what you do...”

We have arrived at the world premiere of the Pepsi commercial, featuring the Jacksons, Michael’s scalp had suffered to make. The ad began backstage at, what do you know, the Shrine Auditorium, with close-ups of Jackie, Jermaine, Marlon, Randy, and Tito’s faces as their stage makeup was topped off, they put on sequined jackets, and Michael’s stand-in’s sequined shoulders cut dramatic angles. (In a sign of his enthusiasm for the product at hand, Michael limited his exposure to a four-second close-up.) The brothers walked through a scrim of people backstage to the stage, but Michael entered through the audience’s aisle, as if he were accepting a Grammy rather than performing a show. Seeing Michael stand dramatically at the top of a staircase, backlit by booming pyro, it was hard not to wince, even before anyone saw the actual footage of Michael’s hair catching fire.

Jackson attended the Grammys wearing a hairpiece. He was beleaguered in other ways as well. Thriller was sweet vindication that he didn’t need the family who’d surrounded him, cocooned him nearly, for his entire life and career. But the accident had come about because that family had insisted he do yet another tour with them—one that Pepsi would sponsor. The Jacksons—just what the world had been waiting for! Especially with Jermaine back in the fold! Wait—were those crickets? Or was it just Joseph, the Jackson patriarch, bending the room’s atmosphere with a furrow of his eyebrows?

The ads were not supposed to be public knowledge—they were intended as surprise spots for the Grammys. Bob Giraldi, who’d directed Michael’s “Beat It” video, was at the helm. The song was “You’re a Whole New Generation,” a Pepsi slogan Michael had draped over the tune of “Billie Jean.” They were doing the sixth take at half past six when Michael, atop a staircase, stood next to a magnesium flash bomb that exploded roughly two feet from his head. Several people—including Jermaine, standing just a few feet away—initially thought Michael had been shot.

Jackson was rushed to Cedar Sinai Medical Center; following treatment, he was transferred to the burn unit at Brotman Memorial Hospital. (He’d visited the latter twice before to cheer up the kids.) There, he watched Close Encounters of the Third Kind on the VCR and took his first painkiller, a Dilaudid. Nearly alone among those near his level of fame, Michael had never before taken a narcotic.

*

Michael doted on kids, quite publicly. In the Shrine audience, to Michael’s left—with Brooke Shields on the right—was Emmanuel Lewis, the pint-sized twelve-year-old star of ABC’s Webster, a family sitcom that essentially cloned NBC’s kiddie breakout hit Diff’rent Strokes, starring Gary Coleman. No one was publicly questioning Michael’s motives for being around those kids yet—those wouldn’t surface for a decade. Michael was a showbiz kid and liked being around others—he’d give Lewis piggyback rides, carrying him around the Hayvenhurst estate, playing cops and robbers like kids half Lewis’s age, and a fifth of Michael’s. What’s a little eccentricity from the world’s biggest star?

Soon Michael and Quincy rose to accept another award: Best Children’s Album, not for Thriller, but for the E.T.—The Extra-Terrestrial storybook album, which Jackson narrated. “Of all the awards I’ve gotten, I’m most proud of this one, honestly, because I think children are a great inspiration, and this album is not for children, it’s for everyone,” he said.

*

When Michael won Pop Male Vocal for Thriller, he said, “When something like this happens, you want those who are very dear to you up here with ya—my sisters La Toya and Janet, please come up.” La Toya wore a glittering headband and a teal one-shoulder dress with a similar gold epaulet to Michael’s—very Wonder Woman. Janet was in a boxy red suit and bow tie.

Michael often used those two as his proxies during interviews—they’d repeat the question a journalist had asked, and he’d whisper his answer to them to give the perplexed reporter. “Michael told me when you hear bad things about yourself, just put your energies into something else; it’s no good crying about it,” Janet told Interview. “Just put it into your music—it’ll make you stronger.” The Jacksons were a competitive family, however loving, and Janet was no different, telling Michael after Thriller hit: “God, you make me sick. I wish that was my album.”

“My mother and father were with us all the way,” Michael continued from the podium. “My mother’s like me, she won’t come up.” Mother Katherine got a close-up anyway. “I’d like to thank all my brothers, who I love dearly—including Jermaine.” Nice qualification; nothing odd there. Finally, Michael’s oldest sister, Rebbie, joined them. Michael also thanked Steven Spielberg (he’d forgotten to earlier) and “Quincy’s wife, Peggy Jones—she was a great help on the E.T. album.” And then he moved in for the kill:

“I made a deal with myself that if I won one more award, which is this award—which is seven, which is a record—I would take off my glasses.” He stood up from his crouch, huge roar, turned back—golly, really? You like me? Shucks—and then put a finger up: “I don’t want to take them off, really, but...” Stood back up, ready for the wave. Finally, he explained that his good friend Katharine Hepburn insisted he take his sunglasses off. A brief hello from Michael’s preternaturally wary eyes; the requisite fan shrieks; a swift departure from the stage.

*

The plummy adult-contemporary singers Melissa Manchester and Julio Iglesias read the nominees for the night’s final category, Record of the Year, without bed music—a silence that, planned or not, jumped the tension on what amounted to a coronation. Manchester pronounced Irene Cara’s hit as “What a Feeling?” like a confused person asking directions. Soon enough, “Beat It” won. “I love all the girls in the balcony,” Michael began. They loved him back louder than ever.

After he and Q ran through their regular lists, Michael also made sure to thank Lionel Richie. “I’ve known him ever since I was ten years old.” Lionel, in the audience, pushed his hands down: Not so loud, a good comedic gesture for someone even more anxious than Michael to win one of these things. He’d been nominated some eighteen times prior to the 1983 Grammys, including seven the previous year, and whiffed them all. And finally, Michael again: “I’d like once again to thank Quincy Jones and the fans in the balcony.”

—Michaelangelo Matos