#481: D'Angelo, "Voodoo" (2000)

—Brad Efford

There’s not a lot of room in my life for country music. I like folk, and pop, not to mention the numb, unconsoling murmur of Swedish alt rock. Sometimes I jam out to 90s confessionals—Nada Surf. Something Corporate. Hey, It’s a Shame About Ray. Stacks of CDs clump in tiny Trump Towers in the foot wells of my car, in amongst the socks and receipts and forever-damp umbrellas. But not one of them is country.

Where I live, in your typical New England landscape, trees crowd close, and it’s a slow, bright creep until winter, when the leaves drop and you can finally see the sky. A daily commute around here might contain the right number of cows and barns and agile steeds to suit a Midwestern ballad, but the barns, mostly for drying tobacco, are in poor repair from disuse, and their support walls have warped like wet paper, giving the whole sloppy scene a lop-sided, fun-house mirror mien.

Instead of cowboys we have tax accountants, slumped over their steering wheels, breathing their soft animal breaths as they flock to the city. There are no quiet streets, no lonesome roads until well after midnight, though the local Starbucks closes at 8 p.m. on Saturdays, and the parking lot of Double Take Double Take Consignment is deserted by mid-afternoon. Still, there are people everywhere you look, taking silent walks down the bike paths at lunchtime, or else making urgent purchases at Benny’s Deli, stomachs clamoring to be fed. At half past five the neighborhood swells with the chatter of traffic. Dogs come out to reunite with their own front lawns. Governed by instinct, I drop my eyes as the Kauffmans march past, little Benjamin, mute with protest, sulking in his red wagon as it trails them.

To tell the truth, I don’t think country music is lonely enough for a place like this. Country music is all about isolation due to a lack of proximity; New England is isolation due to intimacy. The only way to live, when your neighbor’s bedroom is 12 aerial yards from your own, is to not know him at all. How else can you keep your edges clean, and stand fast in your enchantments?

In the Grammy-nominated title track from his 1986 album, Steve Earle promises to “settle down” and take his girl back “to the Guitar Town.” There aren’t any Guitars in the United States (I checked), but if there were, I think the reality might disappoint. According to the song, Guitar Town is just another place where “nothing ever happen[s].” Sure, there’s the siren song of a “lost highway” leading out of town, but there’s nothing appealing about highways. At least, there shouldn’t be. They’re cracked, strewn with garbage, and generally overrun by a cavalcade of businessmen jonesing for smokes. If the strangled lanes of the interstate sound like liberation to you, maybe you should head for somewhere new. But it doesn’t mean things will get better.

Just as country music romanticizes the open road, so too have Americans lathered suburbia with all the fancies of misdirected love. There is just no reason for it. The fewer people there are per square mile, the happier those inhabitants become. We may say there’s comfort in numbers, but mankind exchanged the herd mentality for something leaner long ago.

Illustration by Annie Mountcastle

Take deer, for example. Have you ever seen a herd of deer traveling together (with their little deer valises)? First there is nothing but a thin mist spreading through the trees, the shuush-shuush of your ponytail as it swings against your jacket, the precise sound water makes opening around stones. Even this is enough. You are the loudest thing here; a chipmunk shrinks from your thunderous approach. You still, hoping to appease him, when suddenly they are upon you, flashing past on the left, or the right. Everything narrows to the heat and noise. They are a hot wind. An open vein.

You become invisible in those moments, frozen like the chipmunk, too insignificant to fear. This is where freedom comes from. But in suburbia, the deer travel in twos and threes. They step sweetly through untrimmed grasses, growing stern when approached. A sharp stamp has sent me veering more than once. Deer, like the neighbors, keep a close eye on you. Do I sound like I’m kidding? I’m not.

Don’t get me wrong; I love my neighbors, and I’m pretty sure they would call the paramedics if I fell and I couldn’t get up, but you don’t love something because you need it to feel safe. And you don’t settle in Guitar Town without weighing the delicate ferocity of a deer’s footstep. You don’t forget what it feels like to run.

—Eve Strillacci

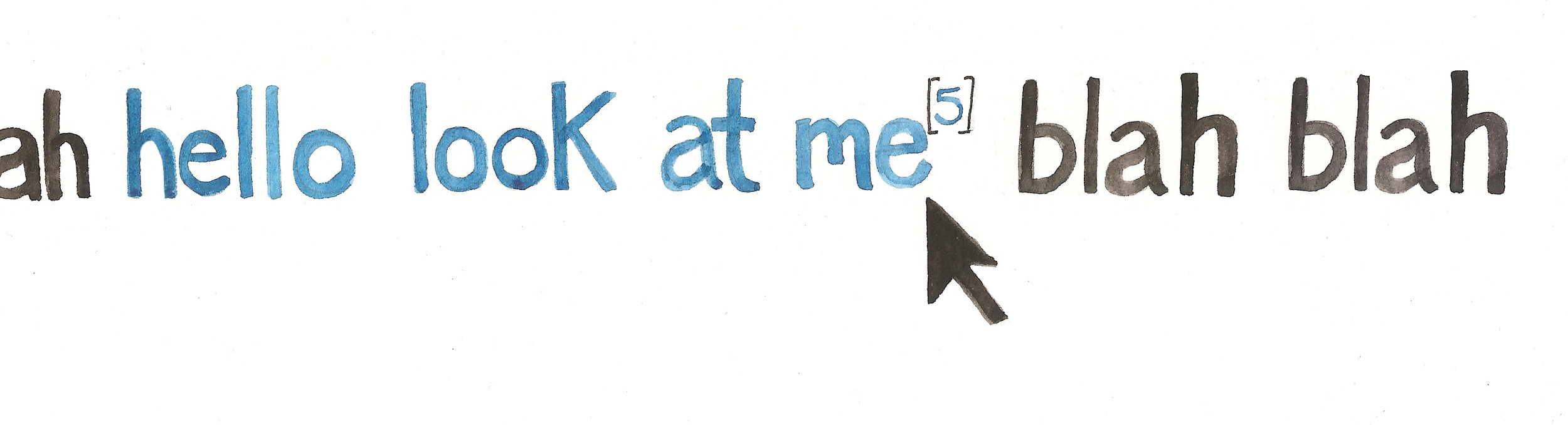

I read Wikipedia articles like “Choose Your Own Adventure” novels, each hyperlink a cobalt pathway to destinations far and esoteric. I begin at the Café Wha? and twelve clicks later I’m at a list of professional darts players. And for the most dire of procrastinators, there’s always the “Random Article” button, the wiki-quivalent of shuffle songs. How else would I have ever found out about teledildonics?

To click or not to click? Dare I disturb the dull hum of informative prose? Every blue word is a gateway, a detour, a trap door that plummets you further and further from the initial inquiry. Infested with algorithms, the Internet is constantly suggesting, recommending, interrupting. Whatever media you’re trying to savor—click this instead.

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

Before I listen to an album, read a novel, or weigh in on Hollywood gossip, I brief myself on Wikipedia, reading just enough to grasp the common understanding. Sure, it’s a secondary, unreliable source, but it’s quick and free and… something about democracy.

Like anything, music is amplified through context, the ethos of a radio station, a coffeehouse playlist, a friend’s Spotify account or an iconic magazine’s 500-best. When we conjure a song online, multiple tabs offer an all-you-can-eat buffet of tidbits and unsolicited commentary. Of course, we don’t always have to multi-task. Maybe it’s not so hard to press play and lie on your bed away from the screen, gazing at the ceiling until you can actually see the melodies dripping through the cracks. One album, all the way through, that’s how I always imagined professional record reviewers do it. The rest of us don’t have time to sign off.

When I type in “Gang of Four,” Wikipedia first greets me with the story of the Chinese Communist faction led by Mao Zedong’s wife, attributed to the deaths of almost 35,000 people during the Cultural Revolution. The most common usage of the term. Part of a series on Maoism.

We must disambiguate. Along with several other political sanctions across the world, Gang of Four might refer to:

Gang of Four, authors of computing book Design Patterns

"Gang of Four,” Big Two card game product

"Gang of Four," Local Management Interface standard for Wide Area Networking

Titled works:

Gang of Four, 2004 novel by Liz Byrski

Gang of Four (film), 1988 French film

Fictional characters:

Gang of Four, villains of comic Riki-Oh

Gang of Four, four heroes of comic Oriental Heroes

Or it might refer to you and your three childhood friends who wreaked havoc on the playground back in the day. I click the link for the band and brace my attention span for more temptation.

Gang of Four are an English band from Leeds, classified as post-punk. Click. Post-punk is a rock music genre, an artsier and more experimental form of punk. Click. Punk rock is music that embraces a DIY ethic. Click. DIY ethic refers to the ethic of self-sufficiency through completing tasks without the aid of a paid expert.

And if I keep clicking, keep wondering, I might just find myself circling back to the Gang of Four page, conquering the click-hole once and for all.

Illustrations by Lena Moses-Schmitt

However I get there, I scroll down to the discography section, for their debut album Entertainment! Click. Released in 1979. Click. 1979 (MCMLXXIX) was a common year starting on Monday of the Gregorian calendar, the 1979th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 979th year of the 2nd millennium, the 79th year of the 20th century, and the 10th and last year of the 1970s decade. The year McDonald’s introduced the Happy Meal.

For the informed listener, is there such a thing as too much context? Back on the record’s landing page, I can hone in on the trivia that might coat my ear drums; If I listen carefully enough, I’ll be able to glean influences of funk, reggae and dub. Red Hot Chili Peppers bassist Flea claims that the first time he heard the record, "It completely changed the way I looked at rock music and sent me on my trip as a bass player." Pitchfork Media listed Entertainment! as the eighth best album of the 1970s. Kurt Cobain listed it in his top fifty albums of all time. What I’m about to listen to is officially Good.

But if I ex-out all those boxes, let the screen fall to sleep as I plop on the mattress, perhaps I can isolate the magic for just 53 minutes. I can pretend these raw sounds exist within a vacuum in between my ears.

I don’t stay in bed for long. Entertainment! is without question an album to dance to, equally suited for moshing and the twist. The bass lick that ignites the first track is as harsh at it is playful, a variation on the dips and thrusts that sustain the entire record. In all twelve tracks, the spittle of the drums and thrashing guitars spew at you from multiple directions, and the bass line always catches your fall.

I could look up the names and faces of Gang and Four, break down who sang lead on which track, his astrological sign and worst childhood memory. Or I could just tell you that the lead vocals on Entertainment! are commanding and sarcastic. Despite the context-blocker I’ve installed in my mind, I can’t hear their British sneer without likening the band to their punk forefathers. The lyrics follow the same formula perfected by the Clash and the Sex Pistols: exposing the dirt behind the daydream:

From “5.45”:

Watch new blood on the 18 inch screen

The corpse is a new personality

From “I Found that Essence Rare”:

Aim for politicians fair who'll treat your vote hope well

The last thing they'll ever do: act in your interest

Look at the world through your Polaroid glasses

Things'll look a whole lot better for the working classes

But what saves Gang of Four from becoming a Mohawked cliché is the vibrancy of their sound. The instrumentation is winking. What’s fighting the system without a few laughs? If we developed anything in the sphere between punk and post-punk, it’s a sense of humor.

The lyricist is self-aware—repeating his sharpest lines over and over to build not choruses, but chants, mantras. Phrases had I left my laptop open, I would make my Facebook status, challenging my friends to the reference. But instead, alone in my bedroom, I shout along with the recording, over and over, until the syllables transcend semantics.

Try it:

I’m so restless, I’m bored as a cat. Three times.

Our bodies make us worry. Four times.

Repackaged sex keeps your interest. Six times.

Guerilla war struggle is a new kind of entertainment. Eight times.

Please send us evenings and weekends. 19 times.

Goodbye. 37 times.

The polemic might dominate Entertainment!, but a few love songs soften the album’s character. True to traditional punk-rock etiquette, the Gang of Four vocalists interrupt each other throughout the entire record, and in the finale song, “Anthrax,” the argument comes to a head, with two voices talking and singing over each other. The chorus, what we’re supposed to be listening to, might be written off as typical adolescent heartache: Love will get you like a case of Anthrax, and that’s something I don’t want to catch.

But there’s a droning voice underneath the melody, incoherent but impossible to ignore. I put the song on repeat, pressing my ear to the left speaker. I catch a few phrases, but after the fifth listen I give up and search for the lyrics on the internet. These are the words literally between the lines:

These groups and singers think that they appeal to everyone by singing about love because apparently everyone has or can love or so they would have you believe anyway but these groups seem to go along with what, the belief that love is deep in everyone’s personalities. I don’t think we’re saying there’s anything wrong with love, we just don't think that what goes on between two people should be shrouded with mystery.

Had I listened to this record B.G. (Before Google), I wouldn’t consider the song a piece of social commentary. I would have accepted the underlying soliloquy as indecipherable, like the thoughts inside a broken lover’s head. Have I cheated, tainted my listening experience? Perhaps the context should stay buried—maybe The Crucible has nothing to do with McCarthyism, and Animal Farm is really just about some huffy pigs.

Any given listener might know nothing of the British punk movement, of the Neo-Marxist rhetoric Gang of Four was channeling in the liner notes. But the same rage, defiance, and absurdist scoff could be felt by listeners in Cairo, Kashmir, or Ferguson, Missouri. And thanks to YouTube and torrent hosts, anyone in those places could stumble upon this record, burn a few mix CDs, and start a revolution. But the record isn’t titled Social Justice. It’s Entertainment!

Entertainment might refer to:

Entertainment, event, performance, or activity designed to give pleasure to an audience

Entertainment (band), post-punk band formed 2002

“Entertainment” (song), 2013 song by the band Phoenix

Entertainment!, 1979 Gang of Four album

Entertainment, 2009 Fischerspooner album

"Entertainment” (song), track on Appeal to Reason, 2008 album by Rise Against

Entertain Magazine, 2007–10 British entertainment magazine

Entertainment (film), a 2014 Bollywood film, also known as It's Entertainment

See also: Amusement.

See also: Distraction.

See also: Coping Mechanism.

—Susannah Clark

Because it is the first Saturday of the month, and Blaine and I are nothing if not creatures of habit, we stop by Zeek's Petz Store and buy another hermit crab. How did this ritual start? Whiskey? Rum? Vodka? It's hazy.

Zeek's smells like urine, shit, and sawdust, which is to say it smells like a pet store. There are the birds hopping and squawking, the ferrets slithering, hamsters tunneling, kittens mewling. The persistent low thrum of crickets. We have yet to see another customer on any of our crabbing sojourns and I have a sneaking suspicion our hermit purchases might be Zeek's only current source of revenue. A desire to keep Zeek in business could be one possible explanation for the six hermit crabs we now own, but a better one would be this: hermit crabs are fucking awesome.

Zeek looks relieved to see us. He must be figuring our aquarium to be getting full, but never fear Zeek, we will buy all the hermit crabs your cramped, strip-mall store can hold. They are sociable animals and, being sociable guys, we try to respect their right to party.

When we get home, we do a few more ritualistic things: we get drunk; we get out the Montana state map and the darts; we put on Mott the Hoople's All the Young Dudes.

The drunk part is because we like getting drunk. The state map and the darts are how we name our hermits. So far we have a Two Dot (who has no dots at all), Laurel (such a sweetheart), Great Falls (who we call Falls Great because he walks funny), Yaak (talkative little fucker), Wolf Point (total badass), and Boulder (he of the hefty shell). It is a perfect system. We plan to market it as a complete kit–shot glasses, map, darts–to expecting parents.

Illustration by S.H. Lohmann

All the Young Dudes is a more mysterious piece of the puzzle, harkening back to the total wastage of our first hermit crab purchase. Somehow–perhaps a raking of the dollar bin at the record store, or a chance encounter with a dumpster–the album came to be in our possession that first night. It's not a good record. It's some empty Stones worship at best. But it turns out Bowie wrote them a song, the title track, and that song is god damn perfect for naming hermit crabs. We put it on repeat. That wavering, drunk guitar lick to start it off! All the fucked up kids trying to figure their shit out. And then those young dudes come in, carrying the news. It's like Bowie wrote the song for hermit crabs. Their own anthem, at long last.

Blaine misses the map with his first dart because he's drunk. I miss the map with my first dart because I'm drunk. I look down at the unnamed hermit in his temporary cage and the little guy is clearly worried. He's looking forlornly at the aquarium across the way, full of his brethren. Never fear, I tell him, we'll get you a name real soon so you can join your buddies.

It takes four throws to hit the map, twelve throws to hit a city. And then, finally, we christen our newest crab. He is Red Lodge. He is red. It is a perfect name. We are drunk, but we handle Red Lodge carefully as we unite him with his new best friends, with the six best cities in Montana.

Mott the Hoople, on their tenth, looping cycle, yell about the boogaloo dudes and I’m so happy we have our little boogaloo dudes, shelled up and Montana-christened, ready to carry the news.

We sit there for the next hour, watching them scuttle and play, getting woozy off Mott’s repetition and, also, beer. What a thrill.

—J.P. Kemmick

1995

Ticketmaster is late to the meeting but he’s allowed to be late because, after a year of insults and accusations, of scathing testimonies and shit talk, Ticketmaster has won. Of course Ticketmaster was going to be late to this meeting if for no other reason than to make the other party sweat a little, make him soak in his failure.

When Ticketmaster walks into the tenth floor board room at the offices of Epic Records, Eddie Vedder is already seated at the end of a long, glass conference table, his fingers pressed to his temples. Ticketmaster doesn’t sit down right away. He walks down to the end of the table next to Vedder, and stands over the young singer. Ticketmaster is very tall and has unnaturally long arms that dangle at his sides, fingers narrowing into thin slits, fine and sharp. Before taking a seat, Ticketmaster gently pats Eddie Vedder on the shoulder and lingers for a moment, waiting for the singer to look up. Vedder doesn’t budge.

After a moment, Ticketmaster traverses the room with three giant strides and sits at the opposite end of the table from Vedder, says, “You called me here today, Mr. Vedder?” Eddie Vedder says, “I did.” Ticketmaster says, “And why was that?” Eddie Vedder rubs his temples again and grits his teeth, then begins to explain that he needs Ticketmaster’s help in setting up Pearl Jam concerts on the East Coast. He says, “The venues we want to play, they all have exclusive deals with you.” He looks down at the table, says quietly, “We need you.”

Ticketmaster pulls two cigars out of its pocket, offers one to Eddie Vedder. Vedder shakes his head. Ticketmaster says, “It’s a Gurkha.” Ticketmaster holds a match to the end of the cigar and puffs so that massive plumes of smoke rise in front of his face. Ticketmaster says, “I wonder how many tickets we’ll need to sell to one of your concerts to pay for a case of these.” He adds, “More than a few, I suspect.” Then, feeling as if the moment has been appropriately savored, Ticketmaster says, “What was that last thing you said? Can you repeat it? I couldn’t quite make it out.” Eddie Vedder looks up at Ticketmaster and, through gritted teeth, says, “We need you.”

Ticketmaster says, “That’s what I thought you said.” Eddie Vedder slaps his hands on the top of the glass table, making the entire surface vibrate, and stands up. He doesn’t make for the door right away, but it seems as if he might. Ticketmaster says, “Sit down, Mr. Vedder.” Vedder obeys. Once Vedder is sitting, Ticketmaster says, “I will help you, but you need to apologize.” Vedder says, “Out of the question.” Ticketmaster says, “Mr. Vedder, you’ve publically attacked me for months. You’ve instigated investigations and legal proceedings all for your misguided ideals.” Eddie Vedder says, “They aren’t misguided.” He says, “You exploit fans.” Ticketmaster says, “We provide a service to fans.” Vedder says, “You increase the price of tickets but you don’t add any value to the product.” Ticketmaster says, “Don’t add any value? Our outlets are accessible to customers around the country. How far did customers drive to buy tickets for the last leg of your tour?” Vedder doesn’t answer. “How far, Mr. Vedder?” Eddie Vedder says he doesn’t know.

Seeing an opportunity to wound Vedder further, Ticketmaster presses the issue, says, “And speaking of value—what of the value you offered your own fans with your most recent record?” Eddie Vedder says, “They like the record fine.” Ticketmaster says, “Only because they’re as misguided as you.” Ticketmaster waits a beat, then continues: “How much value do you think your fans gain from you complaining about the fame they have bestowed on you?” Eddie Vedder says, “That’s not fair.” And Ticketmaster says, “How fair is it to your fans to work hard to buy your music only to hear you barking at them about your small table growing too crowded, and how your ‘p-r-i-v-a-c-y is priceless to you,’ and about ‘all the things that others want from you’?” Eddie Vedder says, “It’s not like that.” Ticketmaster takes a puff from his cigar, knocks an inch of ash on the carpet and says, “Is it that you want to be important?”

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

Eddie Vedder says, “It’s not about that.” He says, “I don’t want to be important.” Ticketmaster says, “Then what is this all about? Your fight against me? Your quibbles with fame? Your causes?” And Eddie Vedder says, “Sometimes I get scared. All these people are watching and I want to do good by them.” Ticketmaster laughs a low, dirty laugh that almost sounds like a growl, says, “So you were doing right by the models when you sang the line about rolling them in blood because they don’t look like you?” Eddie Vedder says, “It’s wrong the ways they have to treat their bodies and then the ways their bodies inspire other people to treat their own bodies poorly.” Ticketmaster says, “So you encourage violence against the models? You disrespect their humanity? You call them skinny little bitches?” Eddie Vedder tries to talk but before he can respond, Ticketmaster says, “And what about the gays, Mr. Vedder. What about the part where you say you’ll never suck Satan’s dick, as if sucking dick is the most vile thing a man can do.” Eddie Vedder says, “It’s a figure of speech. It’s about not capitulating to authority.” And Ticketmaster says, “But why drag, what for some is, an expression of love into your polemic? Aren’t you supposed to be a progressive?” Ticketmaster relishes this moment as Vedder visibly squirms in his seat. Ticketmaster adds, “You’re no better than a common jock.”

Eddie Vedder’s arms fall to his sides and his hands flex into fists. He says, “That’s not what we meant.” And Ticketmaster says, “But that’s what you said.” Eddie Vedder says, “We’ll do better.” And Ticketmaster says, “It won’t matter—you will slowly begin to fade. You have accomplished what you sought so dearly. Outsiders will stop storming your room. Your record sales will fall. You will maintain a base of passionate fans, enough to keep your career afloat, but you will descend into irrelevancy.” Eddie Vedder looks at Ticketmaster with something that almost looks like a smile. Ticketmaster says, “It will be just what you wanted. Your small table, that seats just two,” and Vedder, looking down at the big, glass table, perhaps at his own reflection, mutters, says, “You’ve proved your point.” Then: “What about the east coast.”

Ticketmaster stubs his cigar out in an ashtray, and dials his personal assistant on the phone. As Ticketmaster orders his assistant to begin preparations to sell tickets for Pearl Jam’s east coast tour, his eyes notice a change come over Vedder’s composure, as the singer appears more relaxed than he’s looked in a long, long time.

—James Brubaker

On Fridays I stayed at my high school long after classes ended, wandering the sprawling cinderblock buildings, watching the sun settle in the sky a bit earlier than it had just a month before. It was football season, and come nightfall I’d pull on a stiff polyester uniform—green and black with gold-painted plastic buttons—and pile into a school bus with the rest of the marching band and our director, Mr. Snell, a nearly-silent middle-aged black man who, in my memory, was at least seven feet tall. While other bands covered Top 40 pop songs, Mr. Snell kept us to the classics he loved, focusing on Earth, Wind, and Fire: “Let’s Groove,” “Fantasy,” “September,” and especially “Shining Star,” from their breakthrough album That’s the Way of the World.

The bouncy levity of EWF’s music contradicted the rhythm of my days so utterly that it was almost absurd. In a school of nearly 2,500 students, I waded through over-crowded classrooms and hallways that smelled of bleach and the Chic-Fil-A sandwiches sold in the gym lobby. Mornings, half-awake, I slid through metal detectors and tried to avoid the fights that swelled up from the crowded halls like tsunamis. Like most of the others, I was in marching band because I did not belong anywhere else. I was not a trouble-maker or a Mathlete or a basketball player or a student government politico. I was not allowed to audition for Mr. Snell’s jazz band, his prized possession, either for a lack of talent or for choosing the wrong instrument.

I never saw Mr. Snell smile and I never heard him say we had played well. We’d stumble through a song and look to him, our instruments still raised, to see him give the tiniest wave of his hamburger-sized hands. “Again,” he’d say, giving us another chance, and we’d start over. I had never heard of EWF before learning to play their songs on my clarinet. The arrangements we performed were boisterous, with little attempt at harmonizing. Every instrument shouted all the notes. When Mr. Snell finally told us to stop, to move on to another song, I could never tell if we’d actually improved or if he just couldn’t stand to hear us play the same bars one more time.

Mr. Snell took us to New Orleans to march in a Mardi Gras parade and, another year, took us to New York City, where we wandered the open-air markets in Harlem for hours. We ran our hands over cowry shell jewelry and necklaces featuring the same assorted religious iconography—ankhs, stars of David, crosses—featured on the covers of the EWF albums we’d been rehearsing. At the market, Mr. Snell bought a knitted black kufi hat and wore it for the rest of our trip, and I tried to imagine him as he was in 1975, when That’s the Way of the World was released, chock-full of horns and kalimba and falsetto’d joy. In 1975, Earth, Wind and Fire topped the Billboard charts alongside a whole lot of white guys: Elton John, Glen Campbell, James Taylor, Barry Manilow, David Bowie, the Eagles. I imagined Mr. Snell listening That’s the Way of the World as the world’s ways shifted rapidly, ceaselessly, all around him.

A lot had happened in Memphis by 1975, in the seven years since Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot and killed on the balcony of a downtown motel. By 1975, Elvis was forty years old and had grown puffy and chatty. Still performing to sold-out crowds in his hometown, he would be dead in just two years. White flight was draining hordes of wealthier residents to the suburbs. This migration is often associated with Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, but was also provoked by changing public school policies. In the mid-1960s, Memphis city schools enrolled a nearly equal number of white and black students attending segregated schools. Desegregation efforts were stalled and delayed until 1973, when busing was federally mandated in order to enforce desegregation. Over 10,000 students would be bussed to schools outside their segregated neighborhoods. Members of a group called Citizens Against Busing protested by burying a school bus in a giant pit, and 40,000 of the city school system’s 71,000 white students fled to private, religious, or suburban school systems over the next four years.

In 1975, Memphis was in the midst of a transition that wasn’t resolved even by the time I found myself, in 2003, marching to “Shining Star” on Friday nights. The problems of 1975 still hadn’t been made right. My school was still segregated, but from the inside: the school’s “optional” program was mostly white and its “traditional” program was mostly black, and the two rarely interacted. I was proud to go to public school, but also aware that it was one of only a couple public high schools in Memphis that white kids attended.

Maybe EWF was simply the obvious choice for our band. Their gratuitous use of religious iconography resembled Memphis’ obsession with Egyptian imagery. The Memphis Zoo, covered in hieroglyphics and built to resemble an Egyptian palace, and the huge pyramid alongside the river with its fiberglass statues of pharaohs, are nearly identical to the cover of EWF’s later album, All ’N All. And EWF’s front man, singer, and songwriter, Maurice White, was born in Memphis in 1941. But our school was not one for motivational posters and EWF’s message was so optimistic, so devoid of cynicism, that it’s impossible for me not to see their selection as a deliberate message from Mr. Snell.

I wonder if Mr. Snell thought that, by emulating EWF, with their nine members, two drummers, a horn section, and their miraculously tight, singular sound, maybe we’d also learn something about unity. Over the course of daily practice, after-school rehearsals, summer marching camps, and Friday night football games, those songs lodged a kernel of joy and perseverance into my brain that couldn’t be shaken. I’m sure we butchered those songs. I’m also sure that wasn’t what mattered, in the end. Mr. Snell may not have said many words, but if he spoke to us through Earth, Wind and Fire, the message he chose to share was something deliberately encouraging, uplifting, and hopeful to the point of delirium.

Now, a decade later, in the first cool evenings of autumn, my thoughts often drift to football games on Friday nights, to the high-pitched refrain of “Shining Star” that took up residency in my head. I see myself marching barefoot in the browning grass, or, in the winter, shoving heating pouches into my shoes, struggling to make my cold fingers hit all the right notes. I see myself in my stiff uniform, my too-big hat with its shedding feather plume, with the lights of a half-empty stadium gleaming off the keys of my second-hand clarinet. I see myself lining up in formation, listening for the cadence, my head craned back to see Mr. Snell’s face somewhere up in the stratosphere. And with the wave of his hand, it would all begin again. We’d get another chance to make it right.

—Martha Park

Halloween, 1984. Your best friend Georgia helps you with your hair, which is the finishing touch you didn’t know would be the finishing touch until the hairspray dissipates and you take the visor of your hand away from your eyes to check in the mirror. Then there it is, touched and finished: hand-me-down prom dress, mascara like tribal war paint, bangles and scarves and, all the way up top, her hair like a flame setting your own head ablaze.

The girl in the mirror, she’s gorgeous; you’re gorgeous. Somehow, twelve years old and gorgeous. Wow, Georgia says. Now do me.

Because this was the deal the whole time: you’d get to be Cyndi if she could dress you up all the way, heels to flowing headdress. She’d be Cyndi but she’s black, so you both decide Cyndi’s black friend from the “Girls Just Want to Have Fun” video is the next best, most logical thing. You both know it’s a sacrifice, and secretly you’ve been compiling in your head over and over again all week the list of ways to make it right. Not that something’s wrong. Just incidental. Unfortunate. Whatever.

It doesn’t take as much work to get Georgia just right, which is good. Timing is everything, and right now you’re both too short on it. Sundown is in an hour, which means dusk is now, which means all the best houses won’t last long. Her mom already worked hard on her hair last night, twisting and tying and twisting, so you focus on the eyeshadow and lipstick. When you step away, she looks good. No: she looks great. You both do. Giggling and pouting in the mirror and taking brief dance breaks to flail arrhythmically to “Money Changes Everything” —already, this night feels monumental. Already lit brilliantly from behind.

*

Two hours and seven quickly-darkening neighborhoods later, the high hasn’t lifted. Your pillowcases would drag the ground if you let them, but between banging each other across the butt you’ve got them shoulder-slung like bindles.

I love you more, I love you more, Georgia is belting. Oh-oh-oh-oooooo-wee-oooooh.

When you were mine, you finish, then spin and stop only long enough to pop a handful of Runts into your mouth, bananas already removed and donated to Georgia.

Your route has had you going snaky over the course of the night, winding north, then northwest, then south, and back east again to where you started. It’s the same one you two have taken since you were six and your mom okayed piecing together a Princess Leia gown and pair of side buns. That year, Georgia was a cat, her ears and whiskers and tail made from cardboard and spare curtain fabric. The two of you had just met in Miss Lipton’s class; it’s still one of the best nights you can recall ever having known.

Now, this one’s shaping up to be not so bad itself. The two of you are dazzling, though currently in between houses; this stretch of the route has never been your favorite—all weedy, tricycles left abandoned in front yards, lights more off on Halloween night than left glowing—and the clapboard ranches are separated largely by patches of empty lots. You’re not sure if this is what your mom means when she says “bad neighborhoods”—as in Shuttle quick through the bad neighborhoods, now—but you don’t exactly dawdle.

You don’t realize it, but you’ve been humming “She Bop” for the last block or so, Georgia intermittently taking her Tootsie Pop from her mouth to see if she’s hit the center. So maybe it’s the humming, but you don’t hear it the first time the voice speaks. You only notice when Georgia stops walking for a half-step, then picks up speed without warning.

Hey! you shout, and follow quickly after, working nearly double-time to keep up. Slow down! And that’s when you hear it. Then again. And again. Louder each time—not louder, closer. Closer each time. The voice is not bothering to whisper, not here, not at this time of night. It’s even in tone, almost flat, without affect. Simply making a statement, like someone reading side effects off an Aspirin bottle.

Monkey. Hey, monkey. Hey.

Georgia is walking faster, it seems, with each step. The next house you come to is unlit, but you can see the dim sunrise of a porchlight maybe two or three blocks down. The voice, you can see now, is coming from a teenaged boy in a car riding parallel to the two of you and matching pace. He is leaning easily on the passenger door, both elbows resting on the window ledge, pimpled face peering out from the darkness. You wonder for a moment what this boy might make of your costume—if he thinks your hair looks nice, your makeup and lacy dress—then feel immediately ashamed and determined to make up for it.

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

Go away! you scream, your voice only slightly high, which gives you confidence. Screw off! You hook your elbow through Georgia’s to keep up with her more easily. Her face is set, and when you touch her she still doesn’t turn.

The boy laughs, but only once. Hey, monkey, want a banana? Banana, monkey? He makes noises like an ape, his voice still low, his eyes hard.

Then the car speeds ahead, and you think he’s given it up. But before the two of you can speak, or even slow down, you see that the car has only pulled to the corner ahead—the only one separating you and Georgia from the next house, still shining like a lighthouse. Georgia hasn’t stopped, so you follow suit, the two of you barreling toward the car as the passenger side door opens and the boy steps out, clad in a denim jacket, black T-shirt, and an oversized, hairy gorilla mask. He crosses his arms and takes a step toward you, then stops.

You keep getting closer. Why do you keep getting closer? You are not so subtly trying to steer Georgia to the other side of the street. But she’s paying you no mind, plowing ahead until the two of you are only a yard or so from the gorilla boy, his wide black nose and empty black eyes too realistic in the dark, on this street with no streetlights, on Halloween of all possible nights. Then Georgia stops, nearly tripping you onto your face in its suddenness.

You want to say something, but Georgia beats you to it. She unhooks herself from you softly, and takes the rest of the steps necessary to stand directly before the monkey. She stares at him for a moment, then makes a noise so unexpected you can feel chills crawling up your legs even through your fishnets: she laughs. Not very loud, and not for very long, but it’s her laugh all right. Deep and serious sounding. The monkey doesn’t move.

Man, Georgia says, done with laughing but grinning still. You want a monkey? Her blouse is black and covered in sparkles that catch the little moonlight there is, making her look like a thousand constellations, like the most powerful girl in the whole entire world. Ooh-ooh-ah-ah, she says, running an ape’s speech through the boy’s own affectless voice. The she swings her foot back and vaults it forward and up, catching him with terrible force between the legs.

The boy crumples like a dynamited building, heaving forward and throwing the gorilla mask from his face. He begins to moan quietly and rock from head to toe. You see all of this from across your shoulder, though; Georgia has run, and so, for the umpteenth time tonight, you’ve fallen in line. The two of you reach the next lit house at the same time, then you both bolt past it. You’ve got your prom dress lifted in both hands, which is how you realize that you’ve dropped your candy. The thought blitzes through you and is gone before you even have a chance to care.

*

The two of you--gorgeous, glimmering, brains buzzing with breathlessness--don’t stop until you’re back on your block. Only then, as if communicated telepathically, do you both hit the brakes and start gulping for air. Georgia is laughing, and you are, too: great, whooping laughter caught halfway between adrenaline and drowning.

My . . . . Georgia is trying to say. My . . . candy . . . .can’t . . . breathe . . . .my candy.

Let him have it, you think. Or the cats and raccoons. Whatever gets to it first. Still gasping, you reach up absentmindedly and can feel your hair—her hair—is a total disaster. All the hairspray in the world couldn’t live through tonight. You might care if right now, in this get-up, it didn’t feel so good not to. What you know for sure is that things have changed, that maybe you won’t feel it tomorrow or next week or a year from now, but it seems terrible and inevitable. It’s in the air, the moon, your best friend’s choking laughter.

Soon you will both venture back into your house, past your parents on the couch and up into your room. Cyndi will be waiting in the tapedeck, paused somewhere between songs of liberation and longing. You won’t think twice: you’ll hit rewind, then play.

—Brad Efford

Mary Richards bolts her door at 119 North Weatherly and, after hanging up her coat and setting her shoes neatly beside each other in her closet, turns off most of her lights so the neighbors don’t know she is home. This is long after Rhoda moved out to New York, after Phyllis moved to San Francisco, after Lou Grant died, after Murray’s novel won a Pulitzer, but before Mary meets her future husband, Congressman Steven Cronin, and moves to New York. Mary walks on her toes so her downstairs neighbors don’t hear her, and when she turns her television on, she sits close with the sound low. Mary Richards does these things because her neighbors make her uncomfortable. She doesn’t like that this is the case, but it is.

The girl upstairs is bookish and vague, nice enough, but awkward. Mary met her a few months back on a Saturday, right after the girl—whose name Mary can’t remember for the life of her—moved in. Mary held open their building’s exterior door for the girl, whose arms were full of books. With the warmth she was known for when she was producing the nightly news at WJM, Mary asked the girl what she was reading, and the girl said, “Books,” and hurried up the stairs to her attic apartment. Later that day, bored with the sports and movie matinee options on her television, Mary made a pot of coffee, poured two cups, arranged a plate of wafer cookies and carried the spread upstairs to the girl’s apartment. She balanced the tray in one hand to knock on the door. After a moment, the girl opened the door. Mary was taken aback by the room’s darkness. She said, “I brought some coffee.” She said, “You’ve lived here long enough, I thought we could get to know each other.” The girl said, in a small voice, “I guess.” The girl said, “You can come in.” Then again, “I guess.”

Inside, the young woman neither invited Mary to sit nor offered a place for the tray. Mary started to set the tray on a stack of books. The young woman said, “Wait,” and moved the books to the floor. Mary set the tray down, and smoothed her skirt behind her as she sat on a small, plush chair, covered with a black sheet. Mary asked after the girl’s interests. The girl didn’t answer immediately, and when she did, she didn’t quite answer the question. She said, “Did you know there are approximately 200 UFO sightings reported every day.” Mary said she didn’t know that. She said, “So you’re interested in UFO’s?” The girl nodded her head, then said, “Kenneth Arnold’s 1947 sighting was the first to be shared with a large audience. Now lots of people make reports.” Mary said, “You know, I didn’t know that,” then she asked the young woman if she wanted coffee. Even through her discomfort, Mary was radiant as always. The young woman declined the coffee, but helped herself to a wafer cookie. Then she said, “You know it’s not like in the books.” And Mary, ever somehow both awkward and graceful, said “What? What isn’t like in the books?” And the bookish young woman said, “Being abducted.” She said, “There isn’t a bright beam of light, and they don’t tie you down.” Mary was just listening at this point, not knowing how to respond. The bookish young woman said, “But they test you. That’s why they take you away from your home, from your bed, so they can test the way things feel.” And here, Mary felt something sad turning over inside herself, and reached out to touch the bookish young woman’s knee, which only caused the woman to flinch. Mary backed off and listened as the girl finished her story. The girl said, “That’s why they take you. They want to know how you feel, to know if you are dangerous or weak.” The girl’s use of second person made Mary uncomfortable. The girl continued, “They want to know if humans are friendly. Then when they’re done, when they’ve seen how you feel things, they put you back where you were, on a street or in your bed.” Mary felt like crying, but she didn’t know why, and she felt like saying something, but she didn’t know what to say, so she said, “Oh, I’ve forgotten I need to pick a friend up from work.” Mary left without taking the tray with the coffee and wafers, still untouched save for the single wafer taken by the bookish young woman, and said, “Stop by any time,” as she saw herself out of the woman’s apartment, then out of the building to her car so she could drive aimlessly around Minneapolis for just long enough to seem like she might have actually been picking up a friend from work.

Mary likes to avoid her downstairs neighbors for different reasons. Living in the house’s main floor, in the apartment that Phyllis, and Lars, and Bess used to inhabit, are three young men who keep odd hours and work odd jobs and listen to odd, loud music late into the night. Mary Richards hates that she hides from her neighbors. Ten years ago, when she was still working at WJM, she would have gone downstairs and, not given them a piece of her mind, exactly, but gently asked them to be quiet, to be mindful of their neighbors, and they would have listened because she was Mary Richards, and people liked Mary Richards, and they did what Mary Richards asked. These boys, though, the one and only time Mary knocked on their door to ask them to be quiet, did not like Mary Richards.

The night Mary met the young men who live beneath her, she was, of course, asking them to be quiet because they were listening to music like buzz saws at ten o’clock at night. Ten o’clock! Mary was beside herself, so she knocked on her downstairs neighbors’ door, and was greeted by a man of average height and weight with short hair and a mustache that curled up at the ends. At first, Mary had to struggle not to laugh because she hadn’t seen a man, and a young man nonetheless, wearing a mustache like that since she was a little girl. She tried to ask the man to turn down the music, but the music was still so loud that he couldn’t hear her, so she stepped into the apartment, and shouted, “Can you turn that down?” while covering an ear with one hand and pointing down at the ground with the other. This was enough for the man with the mustache to understand what was happening, so he walked across the room and turned down the stereo. As he navigated the mess of empty bottles, discarded clothing, and piles of books, Mary scanned the apartment, spotted a long-haired man, seemingly asleep on the couch and a third, relatively clean cut young man sitting on the floor, cross-legged, holding a book open on his lap. How these young men could be sleeping and reading through the racket was beyond Mary. Mary also saw, on the far wall, just to the left of the stereo, a poster that read, “We feed the rats to the cats and the cats to the rats,” in large, block letters. There were smaller words beneath. Once the music was down, Mary asked, “What’s the last line of the poster say?” The man with the mustache looked up at Mary, seemingly confused. He looked around. Mary pointed at the poster, said “What’s the small print say?” The man with the mustache said, “And get the cat skins for nothing.” Mary didn’t understand for a moment, then the implications of the words slowly untangled and began to make sense. Mary said, “That’s,” she paused, then, smiling, continued, “nice.” Then she said, “Can you guys keep it down.” Her voice was high, waivered a bit. She went on: “I have to be up early for my job, and I can’t even begin to think about sleep with all this racket down here.” The man with the mustache said, “You don’t have to go to your job.” Mary said, “I have to go to my job.” The man with the mustache said, “It’s just a job.” And Mary, losing her temper, which she rarely ever does, said, “When you’re older and have a real job, you’ll understand.” Before Mary could leave, the man with the mustache said, “I could never be like you,” and Mary had nothing to say, she just stared right in his eyes. She wasn’t sure what she saw there, but whatever it was it was not what she expected—she didn’t see a lazy burnout, but something intangible and wise, gruesome and beautiful at once, a raw depth of emotion and disappointment and anger and grief. Mary said, “No, I don’t suppose you could be.”

When Mary left her neighbors’ apartment, instead of returning to her own, she walked out of the building, and onto the lawn. She looked up at the sky and felt a tightness in her chest. It wasn’t a heart attack, Mary knew that, but she wasn’t quite sure what it was. Her breath shortened and she thought that maybe she was having a panic attack. Mary wondered why she would be having a panic attack now, for the first time, and that’s when she looked up at the roof of her building and saw the girl from the upstairs apartment sitting in a lawn chair, looking up at the sky. Mary wondered if anyone or anything was looking back at the girl, and then her chest relaxed, and her breathing slowed. Right then, she knew that the man with the mustache was right—these people would never be like her, and they shouldn’t be. They were something new, Mary thought, a new day rising, a new type of person. New to Mary, anyway.

As much as Mary hates to admit it, this newness scares her. She doesn’t know what these people are or why they are the ways they are, and knowing these people makes Mary’s Minneapolis feel a little bit darker, and a little bit sadder. So now, most nights, when Mary gets home from work, she keeps the lights and television volume low and walks softly across her floor even when the girl upstairs is on the roof, even when the boys downstairs play their music loud, even when she feels so out of step in this strange new world surrounding her that she wonders if anyone would notice her at all.

—James Brubaker

America’s mythos, based upon the idea of the self-sufficient, self-determining, self-made man, forms the core of our national identity (“anyone can be President!”), but it’s a charming exaggeration. Far more often, America has made its leaps and bounds thanks to a group effort. Thomas Jefferson writes the Declaration of Independence, but it takes fifty-five more men to sign it and make it official. Andrew Jackson has his Kitchen Cabinet; Lincoln his team of rivals; FDR his Brain Trust. Hundreds of people helped smuggle escaped slaves to freedom via the Underground Railroad, even if the only one people can generally name is Harriet Tubman.

I’m not arguing that the site of the Daisy, a 1970s nightclub in Amityville, New York, should be added to the roster of National Park Service sites, but there’s an argument to be made that as far as American grit and determination meeting the group dynamic goes, this Long Island club is a Bizarro World Independence Hall. Because it’s at the Daisy in the spring of 1973, as New York thawed out of another winter, that four boys from New York City first covered their faces with makeup in four different roles: the Demon, the Spaceman, the Starchild, and the Catman. They had played a few gigs with their name already, but it’s on that March night that they truly became KISS.

*

I am not a member of the KISS Army, not even a member of the KISS National Guard, and yet I have been conscious of KISS my whole life, because KISS is an entity designed to make you conscious of it. Eight years before MTV went on the air (and ten years after Brian Epstein put the Beatles in matching suits), they understood that visuals could work with sound to create an entire package, impossible to ignore. Even if I did not listen to KISS, I always knew about KISS, and this is the genius of the band: that they were able to transcend whatever limitations they had in terms of talent or looks or station in life to become completely inescapable in American culture from the mid-1970s to now.

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

This is what makes Destroyer (released March 15, 1976, ten days before I was born) an amazingly contradictory, beautifully American album; like Whitman, it is large, it contains multitudes. From its cover, a painting of the four leaping in full costumes and makeup over a pile of rubble, as though the four heads on Mount Rushmore had smashed out of their stone prison, the albums announces itself as an explosion or revolution—and then it immediately reverses that with its opening track. “Detroit Rock City” starts not with the grinding riff of the actual song, but with sound effects of someone eating breakfast (in a diner? At home?) while listening to a news report on a fatal car accident; this is followed by sound effects of them getting into a car, in which “Rock and Roll All Night,” off the last album (Alive, which saved both the band and their record label), is playing. The song cuts off, then comes back, the car sound effects Doppler across our ears, we hear the driver mumble-singing along with the stereo, the song cuts off again, the engine hums down the road, and then and only then does the riff for “Detroit Rock City” begin—a minute and a half into the album.

Ninety seconds is a long stretch of time, forever on an album. And nothing from this opening skit returns in Destroyer; instead, the album simply moves ahead, doing whatever it likes. Songs like “King of the Night Time World” invite the listener, “living at home” and “going to school,” to join KISS in their midnight universe. Children’s voices giggle over the Demon’s voice and sludgy guitars in “God of Thunder.” “Great Expectations” opens with a riff quoting from Beethoven’s Sonata #8. The album chugs along reliably between songs written to be concert anthems and songs written to invite the listener to escape their world.

And then there’s “Beth,” the tender orchestral ballad (the New York Philharmonic plays on the track), sung by the drummer, the Catman, which became the highest charting track (#7) in KISS’s history. It comes after “Shout It Out Loud,” a song clearly written with the next live album in mind, and the effect is like finding an art museum inside a gas station. The song is two minutes and forty-six seconds of schmaltz, a lover’s complaint that he cannot return to his girl “because me and the boys / will be playing all night” (if the cameo of “Rock and Roll All Night” at the start has any echo, I suppose it’s here). The song fades out, and then the pounding drums and the Starman’s voice begin “Do You Love Me?,” a song so ridiculously over-the-top-rock-star that Nirvana covered it ironically years later. There’s a brief instrumental track, nothing more than a doodle, and then the album is over. It takes about thirty-four minutes, including the opening minute and a half of skit. It’s not exactly an epic album, but then again, the Gettysburg Address is only 272 words long. Does Destroyer contradict itself? Very well, then; it contradicts itself.

*

I have listened to Destroyer dozens of times in the writing of this essay, and it has never improved. Its placement on the RS 500 as an album slightly better than ZZ Top’s Tres Hombres and slightly worse than Husker Du’s New Day Rising feels apt, like the fact that KISS made the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame on their 15th year of eligibility (the same class as Nirvana, who covered KISS and who made it into the Hall in their first year). It is an album that exists more as artifact or evidence of something bigger than itself.

When I listen to Destroyer, I think not about KISS, but rather SMACK, the one-night-only KISS cover band I saw in college, the night before KISS themselves played Topeka, Kansas. In a bar in Manhattan, Kansas, not too far removed in spirit from the Daisy in Amityville, four local boys took the stage in homemade costumes and girlfriend-applied makeup, and proceeded to rock its tiny stage. They did the hits, the ones even I could recognize. The Demon spat blood. The Spaceman’s guitar emitted sparks. A drunk middle-aged woman in the front pulled down her tanktop to show the band her breasts. The Catman came out from behind his drumkit to sit on a stool and croon “Beth” to the crowd, and perhaps I am inventing this detail, but I swear that he gave a rose to a girl in the audience at the end.

They played as best they could given the space they had, in a grotty little college bar called Rusty’s in the Little Apple. The Demon couldn’t breathe fire--a mainstay of KISS’s shows--because of both fire codes and common sense, but we all shouted out loud and promised to rock all night and party every day.

They were four boys in mid-1990s Manhattan (Kansas) imitating four boys in mid-1970s Manhattan (New York), and they were, on that night in April, performing that most American of acts: the invention of the self from nothing. With makeup and costumes, guitars and drums and amplifiers, and a crowd ready to cheer every mood, they were our own Founding Fathers of a moment that was simultaneously imitation and original, carving themselves their own city on a hill out of the wilderness of music and makeup. And I stood there in the crowd, like a spectator watching Lincoln at Gettysburg or listening to FDR on the wireless, amazed at it all, a room full of kings and queens of the night time world in a nation where we always said anyone could become anything, and where, for that night, I believed it, and now, when I hear the long opening of Destroyer, I hear that still.

—Colin Rafferty

When we were nineteen, my twin brother Dylan was in a cover band called the Pink Ladies, which he said was funny because none of them wore pink and none of them were ladies. I thought it was stupid, but when I told him so, he told me I didn’t understand irony. He flicked an imaginary rubber band at me after he said it, and I pretended to bat it away.

This was back in 1997, in those first months after high school, before I married-divorced, married-divorced, before Dylan and I stopped speaking. I was waiting tables at the Perkins by the freeway during the day and taking English classes at the community college in the evening, and on the weekends I’d go with the Pink Ladies to their shows. I’d lug around their guitar cases and bring them warm beers that I kept stashed in a duffel bag in the back of the van. They played weddings mostly, and high school dances, but Dylan, like most musicians, dreamed of striking out on his own and being discovered.

The way he talked about it always made me think of the prospectors heading out to California to strike it rich mining for gold. Dylan was one of the late miners. He’d missed the rush in ’49, was coming along in ’50 or ’51, and all the good claims were taken. It wasn’t his fault. He was born too late for the rock and roll movement, which was what he really loved, and in the wrong place, a small town in northern Minnesota where being famous meant having your hot dish be the first to go at church potlucks. That whole year, our first one out of high school, he talked nonstop about leaving, moving down to the Cities or farther. There were nights when I went to bed feeling heavy and certain that he’d be gone in the morning.

Dylan had the right temperament for greatness, with the ability to twist girls around his finger, to sink into a depression that lasted days, to always get his way, to pitch a fit over something tiny, like when I used one of his washcloths to clean the makeup off my face one night. He was good. He could play guitar, he could sing, make his voice low or high as he needed, growling out lyrics, going up into a falsetto, but he was missing something. He wasn’t great, and he wasn’t original. He was a mimicker. He’d watch videos of concerts, memorize how the musicians twisted and gyrated, and he’d copy that.

I remember one night, Dylan convinced the rest of the band to play ZZ Top. They didn’t normally go in for the rock sound. They kept it lighter, was how Dylan put it, and he always sneered when he said it. Golden oldies for the weddings, pop hits for the high schoolers. ZZ Top just wasn’t in their repertoire. But Dylan loved them, and he loved Tres Hombres. I’d hear him singing in his room, humming guitar riffs, tapping the beat on his stomach. He’d start with “Waitin’ for the Bus,” then move along through the album. It was infectious. He’d started calling me La Grange after he caught me doing it too, and soon that was all any of the Pink Ladies called me. It didn’t make much sense as a name, but it was better than Sexy Sadie, which was what they’d called me before.

It was January, and it was cold the way only Minnesota can be, with that stabbing air that brings tears to your eyes and immediately freezes them on your lashes, streets so slick you could skate on them, mornings of cars refusing to start. The Pink Ladies had been invited to play at a church social, which wasn’t their usual sort of venue, but also wasn’t unusual, since in the middle of January, we were all willing to do just about anything for entertainment. I helped them set up in the basement, untangling cords and testing microphones, which they didn’t need in a space smaller than the elementary school cafeteria, but which Dylan insisted on.

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

You could blame the cold for how it went, the fact that there’d been trouble with the heating and no one had told the Pink Ladies that, so when Dylan hit those opening chords of “Waitin’ for the Bus,” his fingers tripped and froze. You could blame the audience, say they didn’t appreciate the music, say they were uncultured, say that Dylan and the Pink Ladies never had a chance. You could blame Dylan for choosing that night to play ZZ Top instead of in a few months, when they’d play at the high school prom, for a group that might’ve been able to better appreciate it. Singing about Jesus turning the Mississippi into wine would never fly with the good Minnesotan Lutherans.

The whole set was a disaster. It wasn’t just that Dylan couldn’t play the chords right. When he tried to imitate Billy Gibbons’ voice, he squeaked, he cracked, like he was thirteen again and couldn’t figure out how to carry a tune. The fluorescent lights overhead cast a yellow sheen on his skin. Even from where I stood, at the back of the room, almost hidden behind a stack of metal folding chairs, I could see he was sweating. Dylan always sweat when he got nervous. You could just see the rest of the Pink Ladies shrinking into themselves, like they thought that if they backed up far enough, they might be able to just disappear.

When he’d finally played the last chord of “Jesus Just Left Chicago,” the room was silent. Or not silent—someone coughed, a few other people sniffled, trying to clear their sinuses. If one person had started clapping, everyone else would have joined in, but no one started. Not even me. It wasn’t like I stood there and thought through the moment, weighed the pros and cons of initiating the applause, finally choosing not to. It was instinct, telling me to stay silent so that no one would notice me.

It might have been okay if I hadn’t looked back up at Dylan. But I did, and he was looking at me, and our eyes met. We didn’t have many twin moments, Dylan and me, but we had one then. I knew, looking at him, that he would never leave our town, would never amount to much of a musician, would be forever dreaming of what his life could have been, and he, looking at me, knew that I knew this, and something flashed up in his eyes, the type of hatred and revulsion that children have for certain foods, that visceral certainty that if they even smell it, it will make them ill. I could see it in Dylan’s face, and I could feel it in myself, too. Then someone else in the audience put their hands together, tentatively, and the other church ladies joined in. But I didn’t. I dropped my eyes and pretended to knock my elbow against the folding chairs so that I’d have an excuse.

After the show, Dylan joked about it, said every musician needed to have a big flop so he could understand what failure was. And it’s true that for a while, he seemed motivated to get out, to try harder, but that all came to nothing. The Pink Ladies had disbanded by fall, and Dylan started working at the Fix-it-Rite across town, and he never left.

Sometimes I think back to that night, to that moment of our eyes meeting across the church basement, and I think that everything else in our lives followed from that spark of hatred that we shared, and I think that I would do anything to take it back.

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

But then I think, no, that was just another night, just another show, and everything that happened would always have happened, and it was nothing I did or didn’t do that caused it. Then I usually stay up too late watching reality TV reruns and drinking Diet Coke and pretending that the reason Dylan and I don’t speak isn’t because he can’t stand that I know of his failure, but because he’s traveling the world, playing concerts to sold-out crowds, and that any day now he could show up on my front steps just to surprise me. I can see him, the way he used to look after a show, his face pink and damp with sweat, his shirt untucked, the gel dripping from his hair, him running his hand through it and then wiping the grease on his shirt, leaving stains. Or sometimes I see me. I’m back in the church basement, and Dylan’s just lifting his hand from the guitar, his final riff still echoing through the room, and before he can even settle back into his regular slouch, I’m stepping forward, and I’m clapping, clapping hard.

—Emma Riehle Bohmann

On our second bird walk around the neighborhood, Nancy crouched down on the sidewalk, flapping her arms to keep me from stepping on the feather, and shushed me like she was shushing a grenade. To a ten-year-old, her intent was clear: talk and you lose your throat. I kept quiet, but inched closer. Nancy picked up the feather and held it under her nose, moved it in front of her eyes, then settled it next to her ear.

“Sometimes you can hear the squawk,” she said.

I put my ear beside hers and heard a medley of birdsong, but like most everything else, it was only in my head. I held out my palm, hoping Nancy would let the feather float down. It was long and jet black with gray, leopard-like spots and looked softer than silk.

But Nancy hesitated. I was new to the neighborhood and a pretty ratty-looking kid, and how was she supposed to know if I was trustworthy? Nancy loved three dead things more than she loved anything living: John F. Kennedy, feathers of all kinds, and Albert King. Trouble was, she didn’t love them very much, either. Most days, Nancy referred to Albert as the husband she’d have chosen for her dearest, most annoying friend—someone she loved to see in small doses. Albert seemed like a guy you’d need space from. On her softer days, when her hands ached, she called him “Velvet B.” There wasn’t a walk that went by without Nancy humming a tune from Born Under a Bad Sign, which she believed was the only record of Albert’s worth listening to. “The other ones are twice as long, half as good, and three times as fat,” she told me once. But this was after she told me she was a feather finder. She always led with that, as though finding feathers was the part of her that mattered.

Illustration by Lena Moses-Schmitt

Because she didn’t like inviting people in, I only saw Nancy’s feather collection once, a few weeks before I turned thirteen. I thought it was a good sign that something lucky was happening to me before I was about to enter my unluckiest year. Nancy asked me inside, and then took me to her bedroom to stand in front of the nightstand and the shiny box carved from a cherry tree. I could see the moon-shaped reflection of the lamp in the wood. Nancy told me to open it, but I was afraid. What if it were a music box stuck on the blues, and, when I smoothed my hands on the box’s sides, Albert would ascend, granting desperate wishes I never should have wished? Or maybe, the box belonged to Pandora herself, full of every bad thing that ached to get out.

Of course, it was neither. It was a box full of feathers stacked on feathers, arranged from largest to smallest. Some of them smelled bad, and I said so. Nancy said, “Dead don’t go far.”

She was fond of speaking that way, in short pragmatic sentences. I hardly ever heard her expound on anything, and, in general, she wasn’t keen on words. I think that was partially why she loved Velvet B. Nancy didn’t sing many of Albert’s words aloud. “The blues don’t need words,” she said when asked. But I disagreed. I thought the lyrics made the song, and on bird walks I sung nonsense words along to Nancy’s melodies, which often earned me a soft knock on the noggin, her way of inquiring whether or not there was anything in there.

After enough pestering, she let me look at the album cover of Born Under a Bad Sign. I dissected the truly bizarre hodgepodge of a black cat, skull and cross bones, snake eyes, a Friday the 13th calendar page, and an ace of spades on the front, and then I moved on to the lyrics. I didn’t understand how these words fit with the songs I knew, and unlike usual, I was being too literal, asking questions like, What’s in Kansas City? Will I need a personal manager when I become a woman? Who goes on dates at the Laundromat? What kind of gun is a love gun? Nancy didn’t have answers for any of them; she just stated emphatically that I was missing the point. Albert didn’t write those lyrics anyway, and I would do well to turn my attention to the guitar, his fingers on the strings, the riffs and sounds that would shape guitar gods for generations to come.

*

Shortly after I turned thirteen, I left my house one night at dusk to walk off a stomachache. I took the back way to the park, through the gravel alley where I liked to knuckle-thump trashcans and bowl with acorns and squirrels. Circling back around just as the sun disappeared behind the hills, I hopped the fence to my backyard and climbed the rope ladder up to my tree house.

I heard the flapping before I saw the hawk. Trapped inside, it must have flown in the window that had since blown shut. The hawk was red-tailed and his left wing was broken, the bone jutting out into the air. When he tried to fly away as I approached, his body only scooted against the floor. I knelt beside him and looked him right in the eyes, the way you’d look at someone to show you empathized. His talons were curled in and tense from hours of trying and failing.

What is it like to lose your ability to move? To move is to be alive. I imagined my legs falling off and dragging myself across a splintery wooden floor toward a doorknob too high for me to reach.

The hawk crowed. I scanned the tree house and, as soon as I saw it, went for the baseball bat in the corner. I wrapped my fists around the barrel and swung at the hawk until the squawking stopped and the feathers flew. Red, gray, brown and white, tail, flume, bristle and downy, they floated and landed all around the interior of the tree house. I sat, cross-legged, and folded my hands in my lap. I pictured Nancy in her recliner, Albert on the record player, born under a bad sign, toothy licks, gritty and buttery at the same time, D to A to G. I stayed there for hours as the night went black, humming to myself, waiting to be found.

*

Years later, after Nancy had passed, I discovered that scientists have studied which astrological signs are associated with negative human traits. One such study on hospital admissions showed that Aries are more likely to enter the hospital but Pisces are more likely to stay. It was fascinating, and I wanted more. Don’t we all want nature to explain why some of us are lucky, some of us criminal, hurting ourselves and others, some of us so, so blue?

The data isn’t there. At least not yet. I keep going back to the signs, to the knotty horns and the slimy gills. I read the horoscopes and measure how far the moon has traveled from the oak tree in my yard. I have to be honest: the ram and the fish do nothing for me. Their mystery feels too small. And the rest of the signs feel limited, too, as far as explanations go. The virgin and the scales, the bull and the goat and the ugly crab, all so easily lost. The centaur gets close, but then even it is not able to fly. I am looking for a different sign, one that leaves behind tangible things which you can find on the ground or, if you’re lucky, sit among quietly and wait.

—Lacy Barker

Who’s that girl running around with you?

— Eurythmics, “Who’s That Girl?”

As a teenager I used my youth—and my school uniform—as plumage in a years-long tail-feather dance for a few older, adult men. I had designs in learning The Police’s “Don’t Stand So Close To Me” on my guitar, and I rocked my twin bed while imagining running off from Tennessee to California with a middle-aged, B-list actor. In my skewed, pre-feminism adolescence, I saw my youth as both a complement to their age and a roadblock in connecting to them. I started listening exclusively to non-contemporary music—classic rock, jazz, etc.—and watching old television and old films, especially those that seemed to belong to their youth. I threw myself into becoming the girl with knowledge, a grasp of experience beyond my personal experience, my second sight not into the future but, like an ordinary woman, into the past.

Typical of an only child, I sought cultural history as a means to connect to adults, even before puberty. In carpool, I had long conversations with my best friend’s mom while my friend ate Pop Tarts and dozed against the window. I spent summer days with my grandparents watching Perry Mason and insomniac nights watching the full run of Nick at Nite’s retro programming. My music, for many years, was my mother’s music. Bruce Springsteen. Jimmy Buffett. (There’s got to be a home video somewhere of me singing “Why Don’t We Get Drunk and Screw.”) I used pop culture not only as a means to receive adults’ attention—I felt I could access their jokes and metaphors, indeed, their language.

*

Eurythmics’ 1983 album Touch arrived four years before I was born. I first encountered its hits “Here Comes the Rain Again” and “Who’s That Girl?” in the 90s through VH1, a network on which I binged and only neglected for MTV’s Daria. Listening to the album’s nine original tracks and rewatching the two music videos, I yet feel a great nostalgia, like an ink stain over my heart. Or, to use the Eurythmics’ own words, the music returns to me “falling on my head like a memory.” As an adult, I’m most compelled by Annie Lennox’s gutsy gender-bending, exemplified in her roles as both the female lounge performer and the male audience member who kiss at the end of the “Who’s That Girl?” video, especially now that I’m less bullied by hormones and seduced by forbidden (heterosexual) rendezvous, and more in touch with my own leanings. As a teenager, however, my interest in Annie Lennox and David Stewart depended only upon other people, indeed, any person I might want to connect with who had experienced the music in medias res.

In my investigation of the Time Before My Life, I collected knowledge piecemeal, like a panorama made up of many individual images. It’s something I still do through collecting vintage ephemera, pulp novels, smut magazines, science illustrations, music, etcetera. In fact, it’s what I do in writing poems. Some would attribute my behavior to feelings of a particularly hipster breed of nostalgia, a desire to return to some cultural motherland, and some might go so far as to argue that nostalgia reveals one’s inability to live in the present or work for a better future, a vestigial romanticism that makes it hard to crawl out of the turbulent ocean and onto the sunny beach.

But my interest in the cultural past, at least now, anchors itself in empathy, something I feel we must sustain if we are to move into the future with any sort of hope. The wish to make other people more real to me is also why I read literature, why I bought an old radio that reminds me of my dead grandparents. The past, unlike the future, never dies. The past is always the past, no matter if we lived it or not. The time before our birth is full of possibilities, lives we don’t know and never lived. The future doesn’t leave artifacts, but from the artifacts of the past we can make a benign voodoo doll (a bit of cloth here, eye of newt there) with which we don’t control actions but, rather, simply understand them, and, since the past has prompted the present, we therefore better understand our own.

So while I can never experience Eurythmics’ Touch as someone might have the day it was released, I have the gift of experiencing it for myself as a twenty-seven year old in 2014, as well as the experience of my attempt to experience it in the way that others might have experienced it contemporaneously. Additionally, as a poet, I’m constantly seeking new ways to reinvigorate the language I use, and so, experiencing the cultural past allows me to experience the linguistic past, and therefore nudges me, like a good friend, into conversations I wouldn’t otherwise have. My nostalgia, (a word rooted in the idea of going home) is a longing for a spiritual dwelling made up of others, its foundation beams made up of every one I love.

— Emilia Phillips

In the middle of “All Too Well,” one of the most structurally epic fuck-yous pop music has produced in a long time, a very worked-up Taylor Swift lays into her subject with such calculation and heartbreak that it sometimes physically hurts to listen to. Describing the moment to the uninitiated can be a little difficult: essentially, after three verses and a couple choruses of impeccable, brutal buildup, Tay rips through the song’s bridge like a carefully sharpened blade.

You call me up again just to break me like a promise,

so casually cruel in the name of being honest.

I’m a crumpled up piece of paper lying here,

‘cause I remember it all, all, all too well.

Maybe it doesn’t work written out like this. Maybe you have to hear it for yourself. Go now; I can wait.

If you still don’t get the chills you so clearly should be feeling rippling through your body, I think I have your answer. Go get your copy of Red, listen to it top to bottom (skipping “Sad Beautiful Tragic” and “The Lucky One,” because yikes), and see if it makes sense that way. Context can change everything, after all. If that particular album is a massive one for pop music and, more specifically, Swift herself—and it is—then “All Too Well” is the moment you realize its massivity. In other words: if you don’t buy that bridge, you don’t buy Tay, and at least you know you can move on with your life, satisfied that you tried.

I’ve been thinking recently about moments like this: the epiphanic kick to the head that any great album will inevitably eventually deliver. Of course, plenty of albums dish out so many of these over the course of their running time that the very idea of an “epiphany” is ludicrous—it means nothing if every track makes you get it. These are your Aeroplane Over the Seas, your Gracelands and 36 Chamberses. Bonafide chunks of brilliance. Real Mona Lisas.